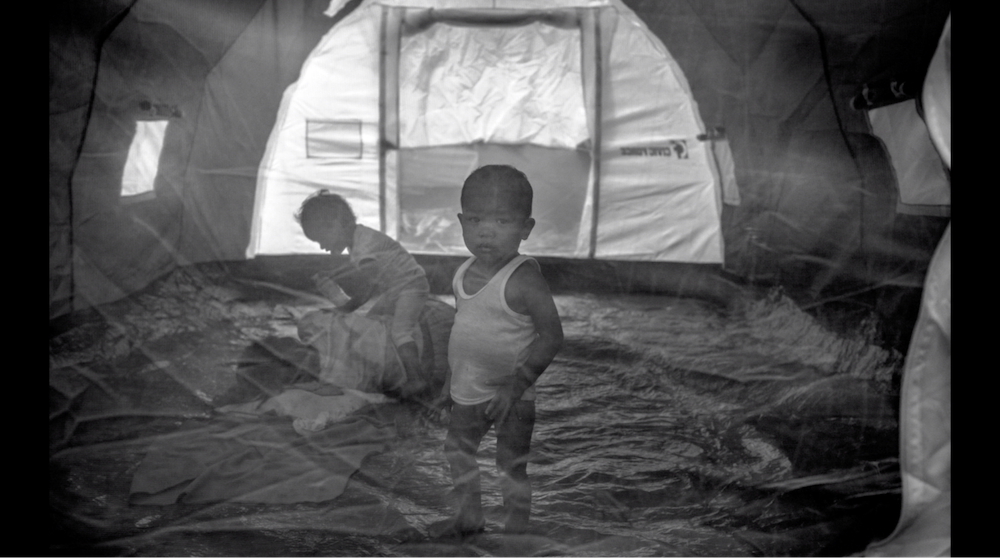

In this year’s Singapore International Film Festival’s lineup, two Southeast Asian short films explore the landscape of tragedy, intimately depicting the psyches of those for whom tragedy has hit close to home, wrecking havoc upon their shores and upending their lives forever. These tales acknowledge the effects of tragedy, wrought by unforeseen circumstances but exacerbated by human incompetency, painting a universal portrait of the resultant wrestling with anguish and pain.

Memory is seen to be a comforting solace as we reminisce about our loved ones, yet also appears to be fickle and unreliable as our longings for the departed turn into hallucinations. More tellingly, the breakdown of memory is explored in those who lost their minds after the disaster. For these, memory now exists as a faulty apparatus, a doomed consciousness stuck in time. Arong herself frequently drifts off into nostalgic rumination of her own deceased grandmother, making for the most affecting sequences of the film. Indeed, the cradling of our memories is our way of dealing with loss, a yearning that the outline of those we love would somehow always exist in our faint recollection.

SGIFF X RICE conducted an interview with filmmaker Joanna Vasquez Arong.

There were many different ways I could have told this story. Once I finally decided I was going to tell the story from my perspective, it felt natural to draw from my own experience and interweave it with the different stories I had come across during my time in this devastated port city. In order to even come close to trying to comprehend the magnitude of this tragedy, I had to reflect on my own experience on grief and trauma. And how we cope.

And it made me consider how trauma when unresolved, stays on and comes back to haunt us, until we finally come to terms with it. I often think of intergenerational trauma. There are times where I’ve felt I’ve been carrying something bigger than my own personal experience. It makes me think that a person could be carrying the suffering of his or her forefathers, and the same applies to communities, regions, and countries even.

For example, from a larger perspective—although I don´t really explain it in the film—I feel the way the relief efforts were handled by the government was politicized partly because of both a personal and national tragedy that has up to now, never been resolved. The father of our president at the time of the storm, was assassinated in 1983, and this had been blamed on the Marcoses who were in power at the time, and who were then forced to flee. The assassination itself, however, was never resolved.

Tacloban, the devastated port city, is the hometown of our former first lady, Imelda Marcos, where the family still carries significant support. And the president, the son of the slain senator, never bothered to properly pass through the city, despite the staggering human loss.

How did you come across the child drawings of the typhoon? I noticed that they were also the only colored elements in the black and white film. What influenced that decision?

When I first started spending time in Tacloban, strangers, mothers, started coming up to me, telling me the stories of their children and how they hoped to find some therapy for them, as they were so traumatized from the storm. Even some slight rain or wind would cause them to go into a panic. Locals also started telling me about the many orphans who were left behind when their parents were taken during the storm.

This inspired me to start a scholarship initiative, Eskwela Haiyan, feeling that perhaps we could find a way to make life a little bit easier for some of these traumatized children. That maybe a few of these students might perhaps have at least one positive association from the storm. The process of finding children to support, who were most affected by the typhoon in different schools, allowed me to hear more of their stories first hand, both from the students and teachers alike.

When I first met with the students, instead of asking them about their experience, I asked their teachers if the students could draw what they had experienced instead. And some of the students voluntarily explained their drawings to me.

As I listened to their heartbreaking stories, the memories and trauma felt very much alive as they recounted their stories, and that’s how I thought it best to keep the drawings in color. It was also a way of emphasizing who the victims are, in these tragedies. I have quite a few of these drawings with me. One day we hope to hold an exhibition of them.

It’s unfortunate but these recurring natural calamities and the response of the government seems to be consistently contentious. Seven years later, and it feels like the film is more relevant than ever. At the height of the pandemic and lockdown in the Philippines in August, our country has once again been rocked by another controversy with massive fraud exposed by whistleblowers. Systemic irregularities in COVID payments from our public health agency have been uncovered with billions of pesos unaccounted for. And just in the last weeks, our country has been pummeled by three typhoons one after the other, with parts of our country still flooded. And what’s consistent is the politicking of aid again.

I do not consider myself an activist, but I felt compelled to share the human stories I had come across, to share the despair and silent rage brewing. Each time a natural catastrophe takes place, I feel we seem to face two tragedies: first the natural calamity itself, and second, the mishandling and even human exploitation of the disaster, which I feel is even more devastating.

What influenced the anecdote on ghosts in your film? Was thinking about ghosts comforting or haunting?

I have always been drawn to stories of ghosts or spirits, so depending on the situation, it can either be comforting or haunting. And deep down, I must admit, I do want to believe in spirits. I want to believe that my two grandmothers whom I was very close to, are still with me, guiding me somehow, if I listen close enough.

So within that context, I feel that thinking about the ghosts in my film is perhaps more comforting, albeit melancholy. Most of the people who died during this tragedy were taken unexpectedly and so suddenly and violently, that perhaps it’s a way for people to cope with the sudden loss, to feel that their spirits are still amongst them. And it’s perhaps comforting to think that their spirits are lingering on until they are ready to finally leave.

That’s an interesting question to consider. It may be subtle, but this is the first time where I allude to my own personal story in one of my films, the first time I brought it out to light. And yet the truth is, I’ve always been drawn, perhaps subconsciously, to the darker stories slowly boiling beneath the surface, unaddressed. And in interweaving parts of my own story, it made me reflect on the lingering effects of trauma, and the root of simmering rage.

Everyone probably carries some form of trauma. How do we resolve it? I feel its in getting to the source of the suffering, shedding light on it, acknowledging it, naming it, which I believe is where sharing our stories is important. Storytelling is a tool to make your voice heard, to be seen.

I feel a crucial step in healing is when somebody hears us. Yet, many of these tragic stories from Tacloban were not being heard, not acknowledged even. In relaying the stories I came across, I felt it was a way of shedding light on the suffering, bringing it to the surface, exposing it.

This, in effect, is the essence of the title of our film, To Calm the Pig Inside.

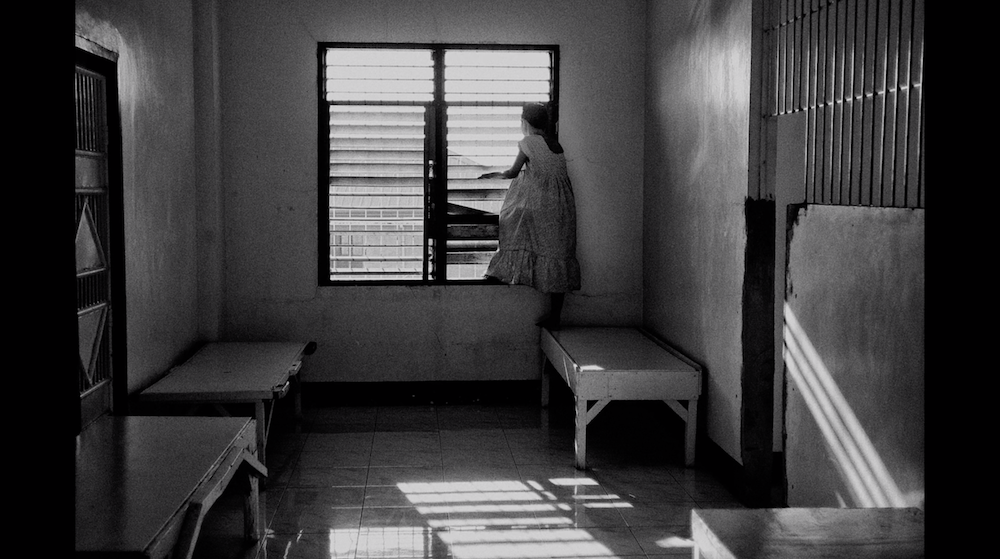

Childlike longing and naive determination are pit against the harsh realities of marital splits as Samuel, a ten year old reminiscent of Moonrise Kingdom’s own Sam Shakusky in his yellow garb (think yellow cap, yellow wristwatch and yellow backpack), sets on a course of endearing resolve to reconcile his estranged parents during the annual Mid Autumn Festival.

While the film does not shy away from the realities of a broken marriage, it ultimately does hoist up a glimmer of hope, a raised sparkle crackling in the pitch black night. In its conclusion, this coming of age story presents the reality of dashed dreams as adversities that one must, and ultimately can, overcome.

SGIFF X RICE conducted an interview with filmmaker Mathias Choo.

Yes, to a large extent, Rocketship is a personal story for me. The film was inspired by an event that occurred while I was in my second year of Polytechnic, one which led to my parent’s separation for a couple of months. The entire process taught me the difficult lesson of adapting to and accepting things that are beyond my control, which is something that many others whose parents are or have separated understandably struggle with.

The genesis of the narrative was formed with that in mind. But of course the film evolved and grew into something much more with my team’s input. Everyone has a story to tell; and I am only grateful that I was able to tell mine with the support of people around me.

What was the process of working with a child actor like? How did you attempt to introduce Isaac to the psyche of Samuel and bring out the nuanced emotions needed for his performance?

It was an insightful and rewarding experience working with Isaac. Isaac had no prior acting experience (we street casted him), and so It was necessary to get to know him better before getting him on screen. Through extended conversations and regular meetups, I was able to find connections that I could draw between Isaac’s personality and Samuel’s character.

It was also important that I shared the inspiration behind the film to provide Isaac with a clearer understanding of what we had hoped to achieve. We were, of course, thoroughly impressed by his maturity for his age—he could easily pick up the emotional transitions reflected within our script. Isaac is such a curious individual, constantly asking questions regarding his motivations within the scenes, and also occasionally suggesting interesting choices of his own.

To ease him into the character, I attempted to utilize mostly improvisational techniques so as to allow for the two cast members to really connect with one another. Karen is someone who is sensitive and very self aware. Hence, she was able to get Isaac to open up, and I think this helped in generating a genuine and authentic connection between both casts which then resulted in a realistic presentation of the everyday.

The stylistic elements in this film are reminiscent of a dated time, from the use of aspect ratio to the faded, nostalgic look of the image quality. What influenced this artistic decision?

The main reason was our keen desire to compliment the use of the sparkler rockets, a key motif in our film. The sparkler rocket provides a strong visual representation of a part of my childhood. It is symbolic of Samuel’s aspirations for his parents’ reunion, and the underlying impermanence of events. On that note, it is also intriguing that playing with sparkler rockets is now something that most children in Singapore would not experience. Placing the film in a dated period is most apt.

The blunt and unrelenting character displayed by Sam’s mum came as a surprise., How did you go about crafting this character? Did you consider softening the image of Sam’s mum in the film?

I did initially consider softening Sharon’s character, but through the character developing process, realised that it would present an interesting dynamic to offer opposing reactions to an event – the separation. With Samuel as the anchor in his parents’ marriage, it is an intentional step to portray Sharon as an independent, strong-headed mother, keen to move forward albeit negatively from her experiences. Sharon embodies the struggle to strike a balance between her own desires, while also catering to her son’s emotional needs through the separation.

Most of our shots had been pre-planned prior to filming with a different apartment in mind. Just weeks before production, however, we were granted access to film in this point block apartment at Mei Ling street. The team was drawn towards the architecture of the house as the layout provided alternatives and opportunities in our visual storytelling.

We did rewrite one scene after being inspired by the set (the scene where Samuel hides the box of sparkler rockets from Sharon), and it would have not been possible if not for the unique architecture of the house.

As for spontaneous moments, one particular event I remember occurred whilst filming the packing scene – I was struggling to bring out the desired performances from the cast. After a few takes, we called for a short break while I attempted to figure out how to adjust their performances. It was then that I noticed Isaac casually interacting with Karen, and cheekily entering the wardrobe to hide himself from her. It was perhaps this playful interaction that was needed, and we attempted the scene again with him trying that for the next take, which was eventually used in the final cut.

Do you think digging into your personal inventory of life experiences will be a mainstay for you? What is a story that you are looking next to tell?

At this point, yes, definitely. I do believe that there is value in tapping into personal experiences as it provides for a lived experience for my viewers. Personal narratives are also an invaluable source of research when attempting to translate preliminary ideas into actual events for a story.

I am drawn towards exploring the notion of growth both in the micro and macro levels. Having had the opportunity to tell a coming-of-age story about a character who struggles to grow, I’m now interested in exploring the other end of the spectrum, of what happens when there’s an exponential excess in growth. I do see this increasingly being reflected with technology and the digital age, and is something that I am currently eager to explore.

Films, then, provide solace. In the moving image, we see ourselves not as mere individuals, but as part of a larger whole that intimately knows and grapples with grief. It is an expression of mutual understanding, an assurance that we are not alone.

To Calm the Pig Inside and Rocketship are currently in competition at the Silver Screen Awards. Catch SEA Short Film Competition Programme 3 online on The Projector Plus.