At 75 years old, Betty L. Khoo-Kingsley has written an apology letter to her grandchildren on behalf of her generation for wrecking our planet.

As she pulls out her laptop to show me this letter at the SG Climate Rally at Hong Lim Park, the suffocating 5 PM heat beats down on my back, reiterating her point by thoroughly soaking through my shirt.

“I admit that my generation is instrumental in causing the dire state of our planet, so I feel like we should be responsible for cleaning it up too. How can we say that it’s difficult when there are clearly solutions?” she says emphatically, listing a school in Thailand that has been powered by solar panels for years.

“Climate change cannot and will not happen without radical action, because we are already past the tipping point. Scientists have been warning us for years.”

Her impassioned sense of urgency evokes an unfamiliar stirring in my chest. It feels like hope.

After all, it is one thing for our youth to care about the state of the planet that they’d live to see, but it requires a deeper level of selflessness to actively protect Mother Earth for future generations.

Barely an hour after arriving at the rally, one of the ‘older’ speakers, Professor Sivasothi from the National University of Singapore, takes the stage. He candidly acknowledges the youth who’ve shown up to fight for their future.

“I stand before you saying we needed a kick in the butt. We are not here to hand over a problem to the government, but we’re saying we will work together,” he says.

“I’m concerned that the world our children inherit will be more hostile, as there are far-reaching implications of a world that has depleted its natural resources,” she tells me.

“I prefer to call it a climate and ecological crisis. Ecologically, it would be a huge loss if our children could no longer see some of the beautiful places or had to look up old photos of extinct animals that did not survive the actions of man. Just like how I have to look at black and white photos of the last Tasmanian tiger in Hobart Zoo today.”

At home, Karen inculcates good habits in her son by talking to him about fossil fuels, renewable energy, and the effects of global warming. She also tries to teach him broader values by reminding him that everyone in society needs to work together to find solutions, rather than just protecting one’s own community.

Since most schools in Singapore don’t prioritise environmental or global issues, she’s adamant that parents need to do their part to educate themselves and their children on these topics.

“People often like to say that we know the issue, but who is really going to make a stand? Most of the people around my age like to complain rather than come together to see what they can do,” he says.

“My daughter is very conscious, such as by reducing her plastic waste and eating more veggies.”

I can’t tell whether the sun is getting stronger, or if I am simply warmed by his sentiment, but hope is no longer a foreign feeling.

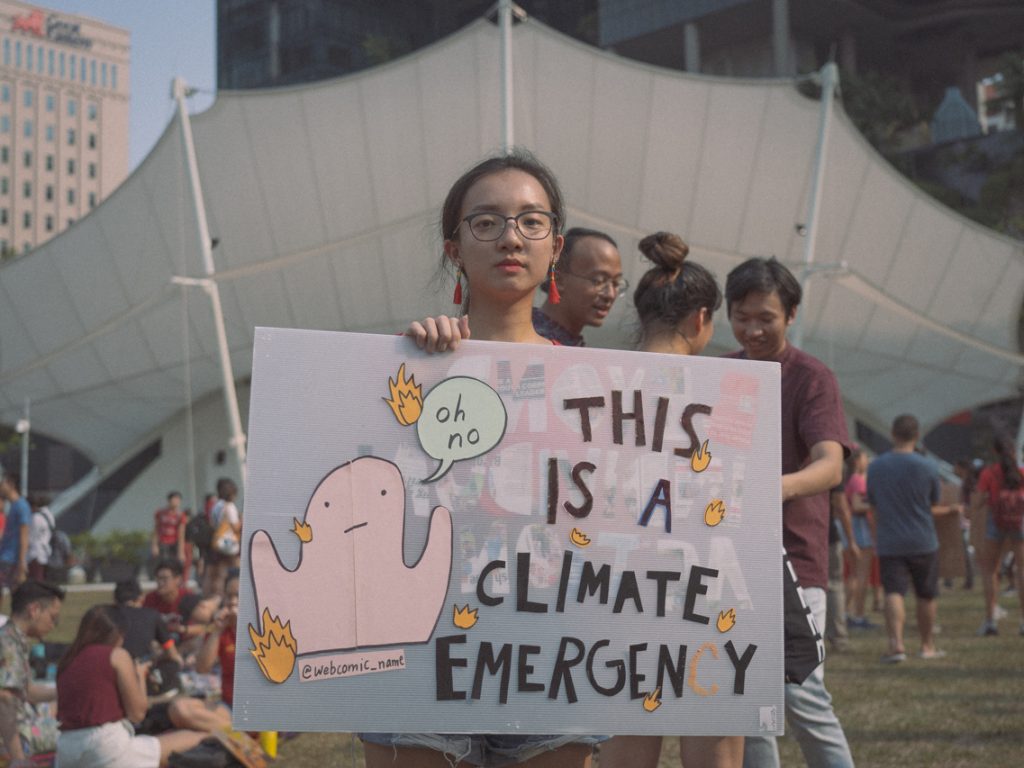

In other words, our youth are aware that merely being inspiring doesn’t cut it anymore.

Prior to attending the rally yesterday, I spend three hours trawling the hashtag #ClimateStrike on Twitter. Each time I refresh the page to reveal another picture of another country, another city, another crowd of tens of thousands of students taking to the streets in what’s possibly the largest coordinated global strike to date, I grow exponentially prouder of the younger generation.

Even though our youth didn’t participate in the worldwide strike for climate change on 20 September, nor take to the streets in protests and marches, the three-hour rally marks a significant milestone in youth activism for Singapore.

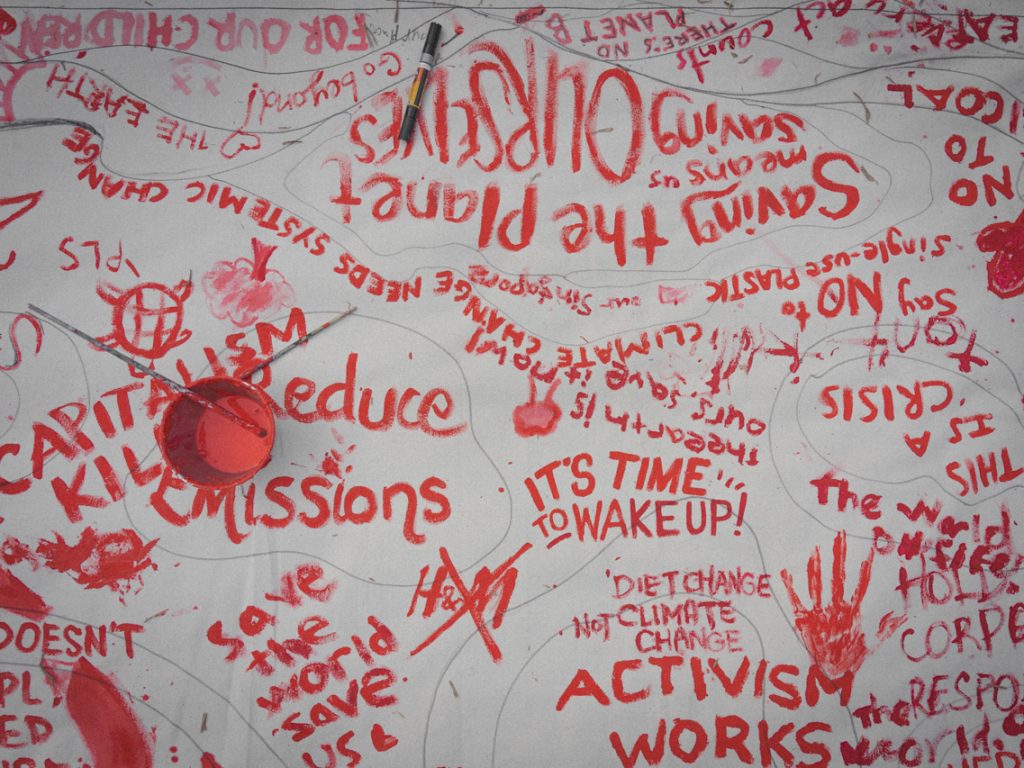

At the rally itself, a sign reads, “Sea levels are rising but so are we”, while another says, “I’m studying for a future that is being destroyed”.

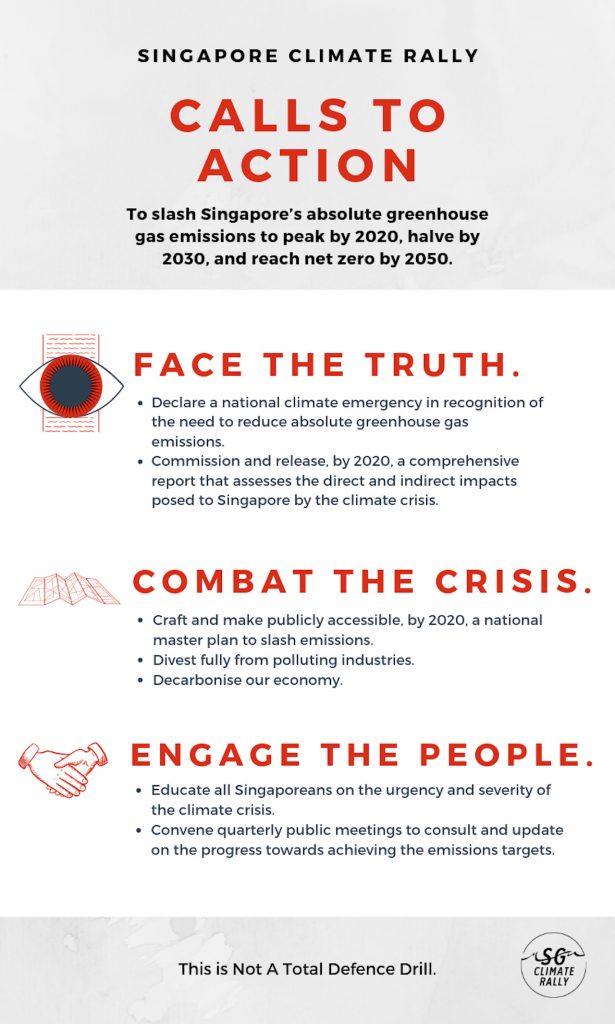

Ultimately, the event pushes for stronger mitigation efforts through institutional change, since individual action is no longer sufficient with the time we have left, according to Komal Lad, the founding organiser of the rally.

“I’ve known about climate change since primary school, because we were taught to switch off our lights and fans when they were not in use. Yet, even now, about 10 years later, there still haven’t been significant changes in our actions or mitigation policies to combat climate change,” she says.

Last year, Komal started making personal changes to reduce her carbon footprint when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports warned that we had less than a decade to drastically reduce our carbon emissions. But recent climate-related headlines, such as those about heatwaves and Arctic wildfires, leave her worried about Singapore’s lack of climate action.

The rally is the perfect avenue to demand that respective institutions heed their calls-to-action. She wants our national carbon emissions target to align with IPCC’s recommended timeline: to peak absolute greenhouse gas emissions by 2020, halve them by 2030, and reach net zero by 2050.

It’s a lofty goal, but at this stage, incremental steps can appear more patronising than progressive.

During his speech, he proposes that our education system include environmental issues as a compulsory subject in school.

“Let’s teach our parents a lesson for once,” he declares, and the crowd cheers and applauds.

At this point, Mother Earth isn’t just burning up—she’s screaming in pain. Anything less than radical, tangible, and systemic change that specifically targets the industries contributing most to the climate crisis is no longer enough to save her from the fire.

But all we’ve done is offer her a glass of water, hoping that will douse the flames.