When I first moved to Malaysia, thirteen years ago, I lived in one of Kuala Lumpur’s less affluent neighbourhoods. My first impressions of the country, and the city, were formed from a modest second-floor flat in a mould-blackened low-rise, low-cost development, where the local drug dealers policed the stairwell. The flat belonged to my wife’s family. They had lived in the area a long time, previously owning and occupying what is sometimes referred to, not always flatteringly, as a squatter house, before the developer’s bulldozers ate the fruit trees, filled the fish ponds, and leveled the chicken coop, along with the house.

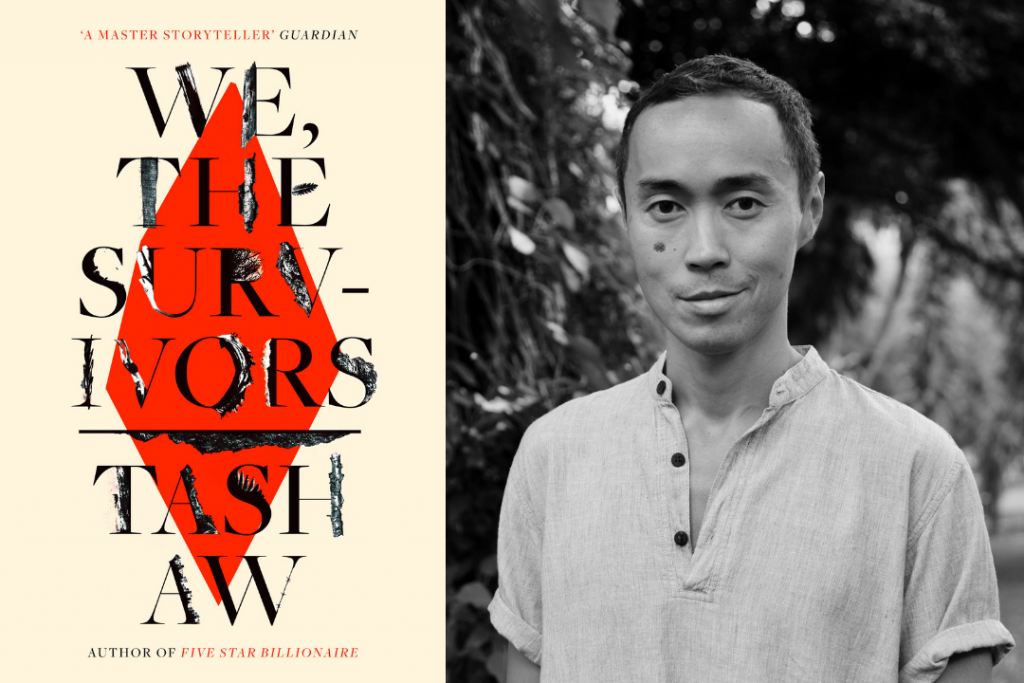

Through my neighbours and my wife’s family I quickly understood that not all ethnic Chinese Malaysians have been blessed with the financial wealth typically attributed by stereotypes. In fact, it took me time to learn that the archetypal ‘rich Chinese’ image was even how many Malaysians view the country’s second most populous ethnic community. Not to say that there isn’t a grain of truth to the clichés—certainly many Chinese Malaysians have done very well for themselves—but that grain of truth is far from the full truth. As such I was glad to see Tash Aw’s latest novel shine a spotlight on what is to some Malaysians a near-invisible community. I could relate to the characters because they were my former neighbours. Some are and were even members of my wife’s extended family. Or perhaps by marriage I am a member of theirs.

The story is framed as a series of interviews, conducted over several months, and interspersed with brief sections where the protagonist observes his interviewer, a young New-York-educated woman named Su Min, measuring the socio-economic distance that separates his life from hers, and perhaps by extension highlighting the potential distance between Ah Hock and the reader.

Su Min and Ah Hock exist in the same time and place, but the intersection of their lives is so small as to be almost non-existent. Nevertheless, a complicity develops between them, each helping the other in different ways; the interviewer coming to Ah Hock’s aid when he is sick, for example, or Ah Hock negotiating the release of Su Min’s impounded car.

As Ah Hock recounts his childhood, we learn that his father has gone to work in Singapore and is “earning a decent wage in a warehouse”. At first it seems like the father might return. He maintains contact. Letters, short on detail, “like a public service announcement” or “a newsreader announcing a headline”, are written in clichés that highlight the contrast between the two countries: “Singapore is very clean. Or, Here, spitting is Not Allowed, Or, No One Has to Pay Bribes Here.”

This story of migration and separation, or versions of it, is a common one. But in this context, it is also easy to read as a metaphor for how two countries went their different ways, one faring better than the other (on a material level at least).

The other main character is Ah Hock’s childhood friend, a small-time gangster named Keong, though ‘friend’ is a loose term here, since Keong might better be described as Ah Hock’s nemesis. Try as he might, Ah Hock never manages to fully escape Keong’s dark gravitational pull, which ultimately drags him to the scene of his crime. Yet, while Ah Hock contemplates his lot from his prison cell, Keong, ever the chameleon, loses his gangster manners and hairstyle, transforming himself.

There are no heroes here—least of all the protagonist—and very little redemption, yet scrape a little at the surface and we see that this is a novel about heroism. As the title suggests, it deals with the feats of endurance required by the characters to simply survive, in what is a largely uncaring and cruel world, where most of the protagonists lead short, hard lives, with little or no occasion for joy.

As an uneducated single-mother with no access to childcare, Ah Hock’s mother is repeatedly ostracised, condemned to work for low wages in a series of dead-end jobs. Again, survival becomes her only goal, her work leaving her too exhausted to raise or nurture her son, who is often left to his own devices, wandering aimlessly around the wastelands that make up the coastal area around the mouth of the Klang River.

While Malaysia’s other dominant ethnicities are almost entirely absent, the Bangladeshi and Indonesian immigrant communities play a significant role, and we understand that they too merit inclusion in the titular ‘We’, that they count among the survivors. Though here, as in real life, many do not survive, falling prey to disease, or the abuse of human traffickers, among other things, including our murderous protagonist.

Malaysia’s chronic overdependence on cheap, and often illegal, foreign labour, is one of the important themes in this book. Aw points out that the type of manual work that might once have been an option for non-academically inclined Malaysians like Ah Hock is simply no longer available, since wages are undercut by those willing to endure the harshest of conditions for what amount to starvation wages.

“If a Bangladeshi worker went to Singapore,” he writes, “he’d earn fifty times what he’d earn back home” but they “mostly end up here, because in Singapore there are rules, permits, all that nonsense you can’t change. Try to bribe someone, you go straight to jail. No permit, no talk. But here it’s different.”

This difference, and the divergence between Malaysia and Singapore, while not the main theme of the book, is repeatedly revisited, and by doing so Aw highlights the moral vacuum that allows the worst kinds of behavior to flourish unregulated in Malaysia.

Perhaps the part of the novel that works best is the microcosm of the fish farm where Ah Hock finds work as a foreman. Like Malaysia, the farm’s success is largely predicated on a plentiful supply of cheap labour. But when that workforce is no longer available everything starts to collapse and spiral out of control, leading the fish farm to ruin and accelerating Ah Hock down his road towards perdition.

Though occasionally Ah Hock seems a little too articulate, in its details We, the Survivors is accurate and authentic, often unflinchingly so. Aw’s use of language is plain and unadorned, giving the story an unambiguous immediacy, as well as perhaps an accessibility to a potential readership his earlier work might not have had.

All in all, this fine novel makes a very welcome addition to the Southeast Asian canon and Malaysia’s expanding store of internationally recognised literature in English.