All photography by Charmaine Poh.

Specifically, I was looking to interview and photograph individuals who identify as “T”, the closest approximation to the Taiwanese version of “butch.”

Tan Liting, the Singaporean playwright and director, had written a play called Pretty Butch, which looks at the lives of five characters grappling with their uneasy place in a world that largely insists on following the gender binary. It was about to be presented in a staged reading at the Taipei Arts Festival, and she had asked me to make these portraits in response, documentary images that when collated together, would begin to visualise what lived reality as T was like. But what did female masculinity look like, and what were the boundaries of butch-ness?

I began by searching for and finding infrastructure that supported this identity: dedicated shops selling a wide array of binders, salons offering permutations of non-binary haircuts, and community spaces to support these journeys. I even found shops selling shirts cut to a typically masculine silhouette, but taking into consideration the generally slender female shoulder width.

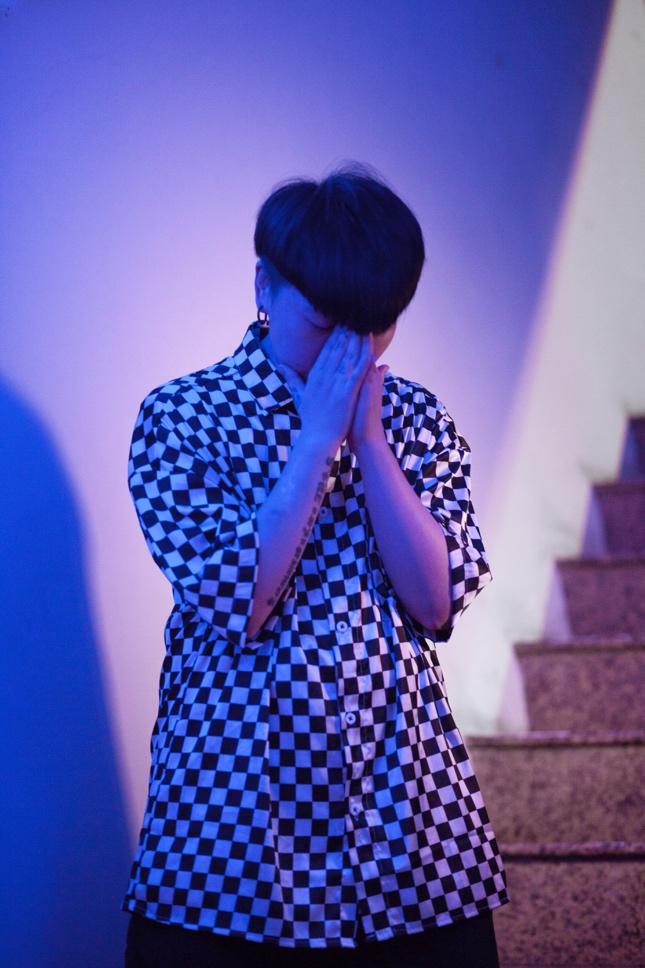

Yet none of us are free from public reading; appearing masculine is also asserting an image that demands to be read as masculine, and with it, the associated power dynamics that exist in mainstream society, no matter the truth of the interior. Being butch inevitably includes an active decision to “do butch”, as professors Audrey Yue and Shawna Tang have written—a nod to the everyday performativity that one adopts in their attempt to construct their ideal personhood. And beyond attire, it also informs the way people stand, sit, walk, talk, and look. I began focusing on gestures as a way to signal these social codes of gender and sexuality, piecing together a puzzle that continually shifts and evolves.

One of the Ts, Hai Ting, who identifies as more of a 娘(niáng)T, gave an example of how it was her girlfriend who pursued her. Another, Eddy, said that she was perhaps “a bad T” because she considered her relationship with her girlfriend to be egalitarian with a disregard for gender norms. In these two cases, the femme partners are both an embodiment of butch desire, as they are an affirmation of the desirability and celebration of butch identity. As spoken-word poet Ivan Coyote wrote, addressing femmes, “Some of them think I am queer because I am undesirable. You prove to them that being queer is your desire.”

As I photographed her, I noticed visible scars on her arm. She told me that in her younger days, confused by her gender and sexual identity, she used to self-harm. These stripes mark the bodies of more than one of the Ts I met in Taiwan. This self-admonishment is present in numerous contexts, especially closer to home, where these identities are even less accepted. A Singaporean friend, who identifies as genderqueer transmasculine, recently told me how they hated the word “butch” growing up.

“It was like a girl who was trying so hard to be a guy but still wasn’t. It was like a mark of…”

“-failure?” I interjected.

“Yes. Failure. That’s a good way to put it.”

It was this that characterised the biggest difference I noticed: “butch” in Singapore seemed to carry a heavier, more negative connotation in comparison to “T” in Taiwan.

When Liting wrote Pretty Butch, she had written a play for all who feel a little in-between everything. It is a play about the best of misfits: those who are brave enough to be honest with who they are and how they want to live.

At one point, she stands alone, front and centre, and addresses the audience. “What does it mean to be man enough, or too manly, especially if I’m a woman?”

A silence follows.

Even when the answers don’t seem easy, and the lines of gender continue to blur, my hope is that these portraits say something true about what it means to carve out a space for oneself to breathe. Long or short hair, binder or not: here’s to pride, without apology.