As Farid walks towards an HDB flat unit, he catches a whiff of the putrid stench of a decomposed body. Instinctively, he raises his hand to cover his nose. Minutes after joining a Muslim funeral services company, Farid is already attending to his first body.

In comparison, his veteran colleague Hamdan strides into the flat to greet a doctor and the deceased’s family.

Hanging back, Farid tries to control his gag reflex.

“Farid, help me,” Hamdan calls, beckoning the younger man into a bedroom. Instead, Farid bolts for the kitchen and throws up in the sink.

Though the TV series premiered in 2017, I heard about it only after attending a course on Islamic funeral rites last month. Some of the students, like me, signed up for the class because they wanted to be prepared when their parents pass on. Others have had the experience of washing the body of a deceased family member, but felt that they needed a refresher class. One participant said she was contemplating a career change.

Muhammad Amir Ali Bin Idris Ali and his wife Raiha Binte Tahir have been teaching the course for about seven years. They also run Pengurusan Jenazah NUR, or NUR Muslim Casket.

Raiha is a jurumandi, and her job is to wash and shroud the bodies of deceased Muslim women, preparing them for burial. Typically, between five and six family members (of the same gender as the deceased) will assist the jurumandi.

Amir, on the other hand, has a more all-encompassing job title of pengurus jenazah, or funeral director. He washes and shrouds the bodies of deceased Muslim men, leads funeral prayers and burials, and drives the hearse, on top of handling administrative work.

“I prefer not to be too serious,” he says. “It’ll make you sleepy.”

As the class progresses, I realise that while I might have had some rudimentary knowledge of the religious aspect of managing a funeral, I had not even thought about some of the most basic questions: Who should I call when there is a death in the family home—the police, ambulance, funeral director, or doctor?

Where do I go to obtain a death certificate? If a death occurs overseas, should the body be repatriated to Singapore?

Amir impresses upon us that any misstep can delay the burial procedure.

During the practical session, one of the men volunteers to be the body for his peers to practise shrouding, while the women use a life-size rag doll.

What strikes me is how vigilant Raiha is in making sure that the aurat—or intimate areas—of the rag doll are always covered with either a seamless batik or towel. For a woman, this starts from above the chest to below the knee. Raiha constantly reminds the volunteers to be gentle, especially when they tilt the rag doll on to its side.

When I visited the couple at their residence a few days after the course to learn more about their work, Amir is keen to hear my feedback. I assure him that I now have a basic understanding of how to help wash a body; I also ask for his name card to stick on the door of my fridge, just like the other emergency contact numbers.

But what has been more difficult to reconcile is the humbling—and uncomfortable—realisation that one day, my body too will be washed, and that I can only hope it will be treated with dignity.

When Raiha shares that she has witnessed some jurumandi handling bodies carelessly, my anxiety increases.

“They don’t bother about aurat, whether they’re gentle or whether they’re rough,” she explains. “They don’t care. They want to finish on time.”

To Raiha, nothing is more important than preserving the dignity of the deceased. Sometimes, she has to deal with an “overflowing of fluid … oozing of blood non-stop [and] faeces” while washing the body. To mask the odour, she lights a stick of incense.

“Dead bodies, they are really helpless,” Raiha adds. “That’s why you must have empathy.”

It helps that they are both in the same line of work because they can learn from each other. At one point during our conversation, Raiha breaks off to tell her husband that she once used makeup to conceal a tattoo on the deceased’s face.

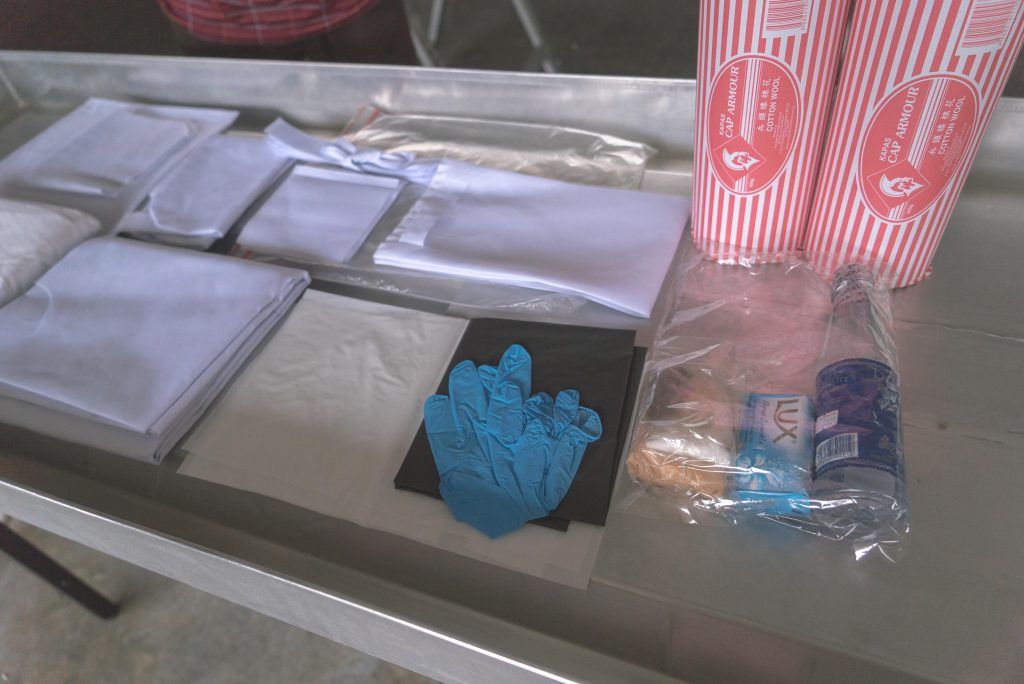

The couple is always on standby, and they sometimes receive close to 30 calls in a month. When they are not working, Amir and Raiha are at home preparing their work materials. They cut bales of white cotton cloth into shrouds, as well as pack plastic bags that each contain sandalwood powder, camphor powder, rose water, Sintok roots, perfume, and a bar of soap. These are the items to be used to wash the deceased.

When I ask the pair what they think of 6×7, they point out the factual inaccuracies in the show.

“We don’t attend to a decomposed body directly at their home,” says Raiha. “The police will not let you near the body.”

In reality, they can only collect a decomposed body from the Singapore General Hospital after a postmortem. They will then wash and shroud the body at Pusara Aman Mosque on Lim Chu King Road. It is also unlikely that a novice would be allowed to take on such a daunting task.

If an individual dies from a known or natural cause, an autopsy is not necessary, Amir says. And they will wash and shroud the body at the deceased’s home.

Raiha continues, “We learned for years. He learned in a few days.”

At 49, Raiha reckons she is one of the youngest among the 20 or so female jurumandi in Singapore. Because of her relatively young age, she occasionally gets “bullied” by meddlesome older relatives of the deceased, Amir tells me.

Based on experience, he can usually spot those who might prevent his wife from doing her job. He tries to preempt the situation by reminding the helpers to follow the instructions of the jurumandi.

That said, Raiha is perfectly capable of defusing such situations on her own. Though she is affable and quick to smile, she is firm when instructing stubborn family members. It is crucial that the deceased is buried as quickly as possible, and any unnecessary disagreements will only delay the process, she reminds them.

A former teacher, Raiha says she has taken courses on human psychology, and knows how to handle fussy individuals.

The jurumandi also has had to deal with odd requests from family members. Raiha shares that some have wanted to keep the bar soap used to clean the body, to be used to shower children who might have difficulty forgetting the dead—think the neutraliser in Men in Black.

Some also believe that bathing an individual with the water that was used to wash the dead can cure him of his drug addiction.

“It’s wrong, you know,” says Raiha. “It’s all ancient myth.”

As Amir sought more hands-on experience, he found himself spending less time with his family. So he suggested that his wife join him. Since most washing requests were made during the day—when their two children were at school—Raiha agreed.

The couple shares that as novices, it was difficult for them to gain hands-on experience.

“Most jurumandi don’t like you following them because they don’t want you to learn,” says Raiha. “To them, every new female funeral director is a threat.”

“Periuk nasi terganggu (disruption to livelihood) lah,” Amir adds.

Eventually, Raiha found a mentor and served as an apprentice for more than a year before being deemed capable enough to “go solo,” as she puts it.

When the couple established their own company in 2009, their customers were mostly friends and families. As part of their publicity blitz, they looked up the addresses of Muslim residents in the Yellow Pages and mailed them flyers.

“Glue, glue, glue. Stamp, stamp, stamp. Post, post, post,” recalls Amir. He even shudders as he remembers the paper cuts he got.

A breakthrough came three years later when the couple began to run funeral management courses. Their social network widened and their business grew.

Today, the couple instructs in English and Malay at mosques, learning centres, private homes, and the Muslim Converts’ Association of Singapore, also known as Darul Arqam.

Sometimes, course participants express an interest in shadowing Raiha to gain more hands-on experience, perhaps even to become a jurumandi one day. She usually takes them along to work at least once to assess their suitability, though most do not stick around for long because of family commitments or economic considerations.

In 2014, the Berita Harian reported that as veteran jurumandi have grown older, there has been a lack of younger successors, especially amongst women. One funeral director has suggested the low salary ($100 per job) as a possible deterrent.

Yet Raiha opines that if one were to raise the salary of a jurumandi, then the cost of the funeral package would also increase.

“You cannot charge people too high,” she insists. “I think it’s not right.”

Being in such close contact with the dead has also given Raiha a better appreciation for life: “You feel that your time is near. Everyday is a blessing.”

With both their adult children having their own careers, Amir and Raiha say that it is unlikely they will take over the family business. When the time comes and they are too old to work, they will simply shut their operations, Amir says.

“Or pass it down to our students,” adds Raiha.