A minute’s walk from my place, there is a temple. Even though my Taoist grandmother has been living with us for over six years, she hasn’t been to it once.

So it remained out of sight and out of mind. Occasionally, lambent music and laughter would crackle through the night, like wayward sparks lighting up the dreary neighbourhood. I’d know that the temple was still alive and well; it wasn’t a part of my culture but it reminded me that it was an integral part of others’.

While this temple is still there, the same can’t be said for many historical buildings in Singapore.

In Singapore, talk of ‘culture and heritage’ tends to conjure connections to the tangible: buildings, food, rituals, festivals. They are visual, tactile artefacts that commit events to memory; public cornerstones that we can visit again and again.

When we then lose them, it feels like a fragment of our collective identities being stripped away. And we will continue to lose these landmarks as modernisation bulldozes anything that outlives its pitiable lifespan.

So what can we hold on to?

From Victoria Street To Ang Mo Kio (FVS2AMK) is a film about loss, which permeates the 70-minute documentary. Commissioned by the St. Nicholas Girls’ School (SNGS) Alumnae Association, it’s also an archive of Singapore’s Chinese schools’ precarious history.

Loss of language, hence the loss of culture; although a colourful cast of characters prevents the film from wallowing in gloom and doom.

First we have the students: inquisitive, vibrant, and always up to something. Amongst the staff, there’s the headmistress Sister Francoise. A personality larger than life, she is brusque, authoritative, and—as director Eva Tang tells me—very Cantonese. The mischievous interplay between students and teachers gives the film much needed breathing room and, more importantly, imbues it with heart.

The film’s central conflict makes itself known within the first few scenes. The English schools are getting everything, and the Chinese schools are left with zilch. Educational policies heavily favour English speaking schools, with English becoming the official language of Singapore.

The girls can’t even play ball during recess without those pesky students from [unnamed English school] driving them off the court.

This is especially heartbreaking when a promised new campus gets allocated to an English school instead. The camera lingers in these reaction scenes, allowing expressions of hope and disappointment to bloom in their entirety. The black and white grading of the film’s first half doesn’t just evoke nostalgia. The hard lights and deep shadows emphasise the emotional weight of the characters.

Even Sister Francoise’s disciplinarian facade crumbles away when faced with the indignant tears of her girls. As the students’ quivering voices sing the St. Nicholas’ school anthem, she embraces one of them, strained smile on her face. The moment feels poignant instead of cheesy because we’ve seen these students treated like second class citizens in their own country.

The documentary also makes it clear that it wasn’t just Chinese speakers who suffered. All non-English speaking communities were affected by these policies. Forget Chinese privilege—the true elite were those representing the Western world. Thanks colonialism! It’s like you never left.

As policies became stricter, it was time to adapt or die. This was the beginning of bilingualism, which the film’s second half captures by splicing interviews with images from the late 70s and 80s.

Though we’ve written about how Special Assistant Plan (SAP) schools are no longer relevant, back in the day there was a pressing need for it. In order for the Chinese speaking community to transition into one that could speak English yet retain its linguistic roots, special assistance had to be given to the secondary school students. This radical restructuring metastasised as the Immersion Program.

Language immersion is specifically employed in bilingual language education, where two languages are used to teach various subjects. Imagine puzzling over trigonometry in language A, while scrutinising the Treaty of Versailles in language B. This was achieved in Singapore by pairing up SAP schools with an English school counterpart. In the case of SNGS, Raffles Girls would be their ride-or-die.

Every day, after school, the St. Nicholas girls would be shuttled en masse to RGS for extra lessons conducted in English. Think of it as a more intensive remedial.

For two to three years, this was the drill.

This bizarre, convoluted arrangement would act as a bridge to the status quo we know today. The language of instruction for all schools would be in English, and for Chinese students, Chinese would be offered as a mother tongue.

We can see the effects of these policies today. Singaporeans are supposed to be bilingual, but we have an entire generation of Chinese Singaporeans who aren’t proficient with their ‘mother tongue’. Times have changed, and our people with them. But when we can no longer speak a language, we are limited in our understanding and expression of cultural experiences.

Singapore has truly come so far, and we’ve sacrificed as much in kind. Was it worth it?

“Oh, I wasn’t part of the Immersion Program, but there was still a lot of moving around between various schools,” Moi Lre tells me. “I graduated at the new campus in Ang Mo Kio.”

I tell her that school spirit must be strong for a bunch of teenagers to willingly bumble around Singapore for their education. And there’s also an entire film dedicated to them now.

“Adversity strengthens school spirit,” she replies. “There was definitely bonding and pride over this collective hardship. But can you imagine if this happened right now? Parents would be complaining all the time!”

She neglects to say if she’s one such parent, but skips ahead to mentioning her two daughters in SNGS: “It’s very different for them now. It’s not really a Chinese school anymore.”

I’m reminded again of loss.

There is no doubt that the loss of our tangible cultural markers is a tragedy. We reside in the same space as them, and their physicality shapes us and our experience of the world.

But what sits with us long after the images, the sounds, the tastes and textures have faded into obscurity, is a feeling. That gut instinct; that annoying, inexplicable reaction that can’t be put into words; the drop on a rollercoaster mellowed into a hum that itches in your chest.

It’s the warmth when the cai fan auntie calls out “ah boy!” and gives you more rice because you look “so young, so shuai!”. It’s when you wordlessly give up your seat to an old man and he accepts your kindness with stoicism. And it’s the apprehension when your friend’s family invites you over for Hari Raya, and you have no idea how to behave, but they don’t really care.

This is culture as a feeling.

And that’s what Eva Tang tried to capture in her film.

“There are people who aren’t old girls who watch the film but they tell me that they still relate to it. It’s the gan jue—the feeling—that I wanted to convey and which I think struck a chord with the audience.”

That feeling lingers in the awkward but earnest laughter when Sister Francois clumsily jokes with a new teacher. Beneath the boisterous brouhaha is the ruthlessly pragmatic notion that the teacher was only hired so the students would be forced to speak English.

It’s conveyed in the spirit that collectively possesses Chinese students to bow when greeting teachers, while English students watch on perplexed. Isn’t this the proper way to show respect to your elders?

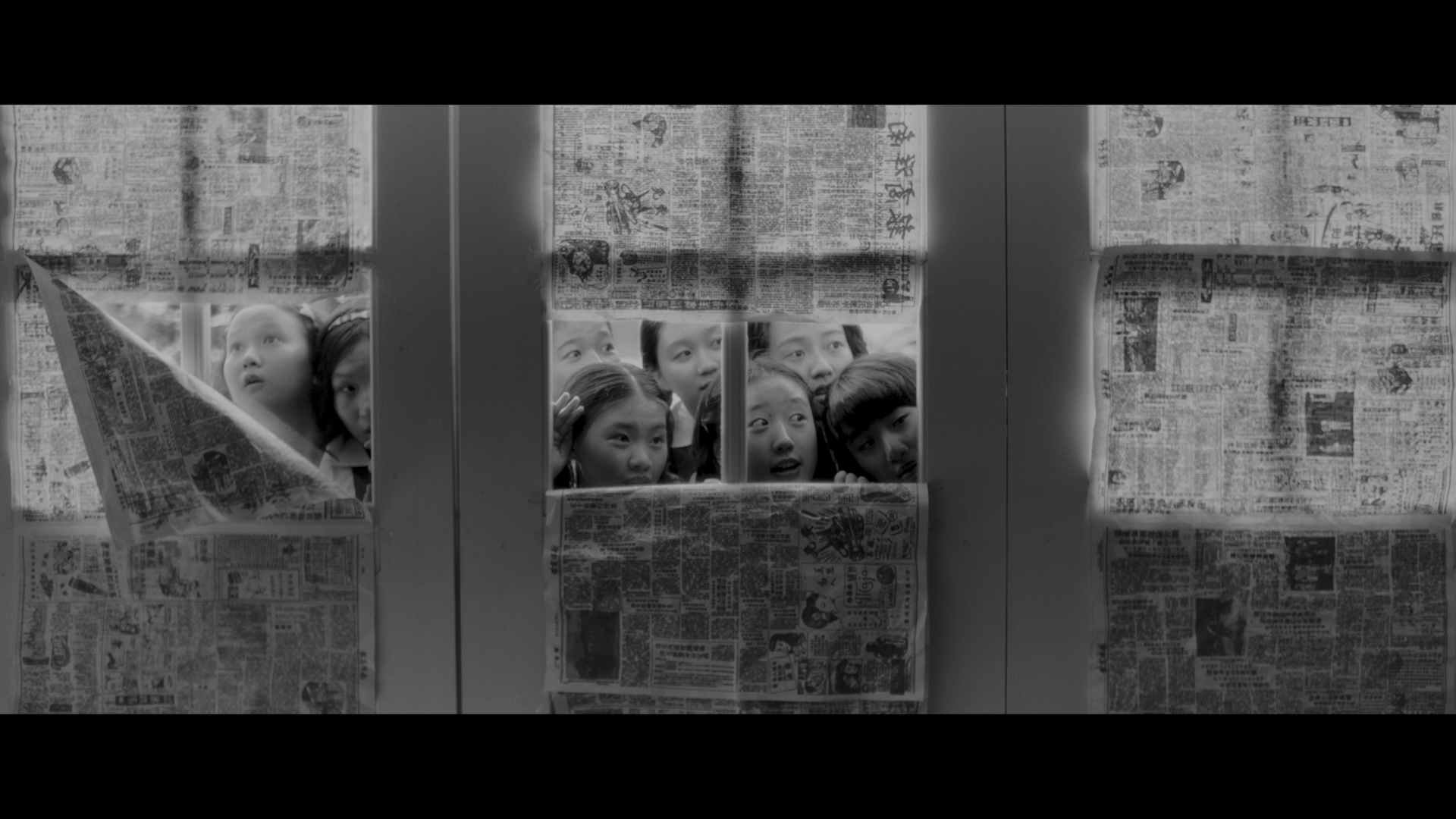

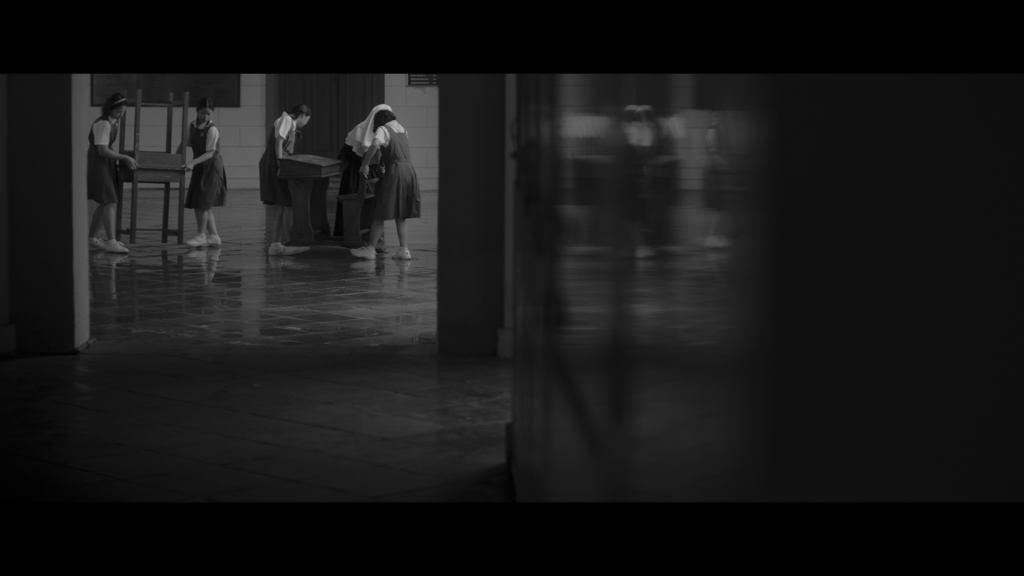

And it’s all over the students’ faces as they peep through gaps in newspaper-covered windows, looking with wonder at what was supposed to be their new school. The feeling transmutes as disappointment takes over, and the girls grit their teeth and soldier on. It’s not resignation, but a Confucian understanding of hard work and sacrifice that would leave the Soviets astounded. The girls would continue to drag tables and chairs through puddle soaked corridors because they know the value of education.

These bittersweet vagaries are hard to grasp but they exist. Each person’s feelings are deeply personal, and that’s part of what makes it so hard to articulate. But there’s a thread that stitches them together, weaving through each of us to form a collective unconscious. We can leave a film together and understand each other’s intimate sentiments, even if it’s tough to express what we’re feeling.

And that community of shared experience, isn’t that culture? Isn’t that our heritage?

What struck me the most was just how many old girls returned with their families. And there were young girls—SNGS students most probably—who brought their parents along. It felt like intruding on an extended family reunion.

These feelings are a legacy. We pass them on from generation to generation through stories like FVS2AMK, sharing histories as they relate to our present, and imagining a future to live in. As Eva shared, you don’t need to be an old girl to identify with that feeling. There’s something in art like this that we find touching, that we find a connection to.

That’s something that can’t be taken away so easily.

Amidst loss, here’s something we can hold on to.

Did you feel something you couldn’t quite describe while reading this? Try writing in anyway, at community@ricemedia.co.