All images by Zachary Tang unless otherwise stated.

If the Global Times wanted to shame me publicly, they’d simply have to publicise my Higher Chinese grade (D7) and my major in university (English literature). Or that time when I directed a clueless tourist to NTUC FairPrice after she asked for the location of the nearest 酒店 (literally ‘wine shop’, but translated as ‘hotel’).

So I was obviously the perfect candidate to write about Huayi, the Esplanade’s long-running Chinese Festival of Arts. If a banana, jiak kantang, ang moh pai like me can learn to love the art—and language—of his forefathers, then surely anyone else can. Right?

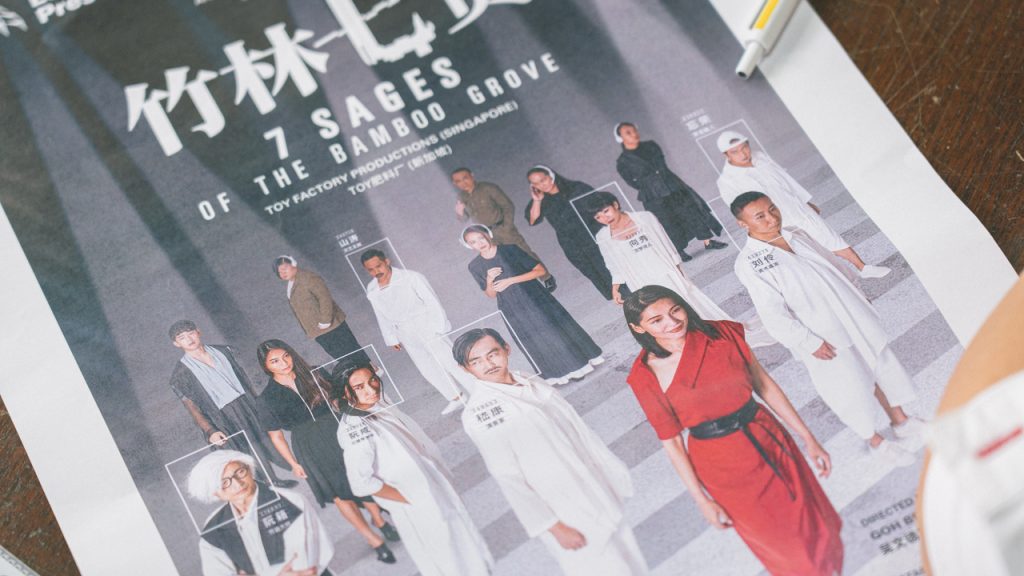

Toy Factory’s rendition is set in a futuristic, dystopian world where citizens are continuously disciplined and monitored via individual headsets, and all artistic endeavours are forbidden because they are deemed to threaten state control. Jun Hong plays Ruan Xian, a violinist who joins a band of 7 artists plotting a revolution to overthrow the dictatorship orchestrated by the dazzling, clad-in-red Sharon Au (see below picture).

Despite the modern (and pressingly relevant) premise of the show, from my point of view, only elderly cheena people would watch and get involved with Chinese art. Thus, prior to meeting Jun Hong, I steel myself for an encounter with a slightly decaying old man reminiscent of my Chinese teachers who have collectively left me with lifelong trauma associated with the language.

Imagine my surprise, then, when a sprightly 29-year-old shows up and warmly greets me in one of those unplaceable, cosmopolitan pan-Asian accents.

After all, he is more well known as one of Singapore’s most accomplished violinists. More to the point: his experience with the Chinese language is one as flecked with terror as mine. He tells me, “Out of all the subjects [in secondary school], Chinese was the scariest for me, especially the oral section. You have to improvise on the spot!”

“Furthermore, my parents speak English at home … [When I became a violinist], I did some interviews in Chinese, like with Zao An Ni Hao. I would just pause and hesitate, and replace certain [Chinese] vocabulary with English. I was pretty embarrassed but I had no choice,” Jun Hong laughs.

Initially, Jun Hong struggled with the script of 7 Sages as well. Before casting Jun Hong in the role of Ruan Xian, Jiang Daini, the company manager of Toy Factory, made him record a “two paragraphs, decently long” monologue in Chinese.

“I’m definitely not super comfortable with Chinese and the text was quite complex, so I didn’t know some of the words,” Jun Hong confesses.

“I had to Google some of it. But it was hard to Google because if you don’t know how to pronounce the word, you don’t know the hanyu pinyin. So you can’t Google it.”

Ah, the classic Catch-22 of the Chinese-challenged. And the age-old solution to this conundrum:

“For words I couldn’t find I just made up the word.”

So why would someone more ang moh pai than me decide to act in Chinese in front of over 2000 people over 2 nights? More importantly, can he convince me of the method behind his madness?

From this point of view, languages like Chinese or Tamil give character to the art and help to convey a message, but do not form the body of the art itself. If this sounds abstract, just think of Korean drama serials and movies.

“I’m pretty sure you watch Korean shows,” Jun Hong asserts. He is right: I had just caught Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, a movie entirely in Korean, at The Projector.

“Why did you watch it? The whole reason why you watch a show in the first place is not because of its language. But because the show is great. The language doesn’t matter, right?”

I concede that point.

His personal experiences performing in cosmopolitan orchestras have reinforced these sentiments. “When you play together in an orchestra, the communication is still there [even if everyone speaks in different languages],” he recounts.

Likewise, for theatre, language is not the issue.

“Knowing the words and saying the words [for 7 Sages] is not that hard. What’s tough is believing and going into the character.”

In any case, Jun Hong notes that “just because a play is in English doesn’t mean [audiences] will come. They will only come if they think it’s great.”

To put it differently, he is suggesting that—to adapt a phrase from the diversity playbook—he does not see language, because, he says, “the art form is the one that’s tying it all together.”

“So I wouldn’t associate [art] with different languages. I don’t see language as a barrier at all.”

From this perspective, the language of any art performance remains essential in drawing audience members.

Take classical music, for example. Jun Hong doesn’t deny that it’s hard to get Singaporeans to attend classical music concerts “because [music] has no words, no plot, no background,” which makes us feel that we lack a language and framework with which to understand them.

This is the same obstacle faced by non-English arts events.

But we shouldn’t be so hung up on trying to understand art, Jun Hong counters. Whether classical music performances, Chinese art festivals, or contemporary dance, we don’t have to know what we’re supposed to listen to or look out for. Instead, “you go in to experience something you haven’t experienced before. Something fresh. Something inspiring.”

The logical conclusion of this thought is that we can, and should, enjoy performances on our own terms. We don’t have to process a play’s deconstruction of the mind-body duality, expressed in rhyming Classical Chinese (for example) in order to enjoy the show.

Everyone is inspired by different things, so if we attend a Chinese theatre show because we adore a particular Mediacorp actor or are enraptured by the fabulous costume design, there’s nothing wrong with that. Ignore the uppity culture snobs who tell you otherwise.

Jun Hong elaborates: “I think the only reason why people will come to a show is if the show will have an impact on them, if they’re able to connect with the show and have some personal resonance with what’s happening.”

The worst thing to do actually is to tell the audience to go in to learn Chinese, learn classical music.

No one can deny that in some societies, we seem to be hurtling disastrously towards the form of government presented by 7 Sages. With a globally aging population, the heart-wrenching tale of a father’s dementia in The Long Goodbye is all the more relevant to audiences. And Prism of Truth, a multilingual, mixed-media experience that dramatises a court trial to interrogate the meaning of fact, is, in our post-truth, POFMA era, a startling reflection of our society today.

Yet for the longest time, I’d been fixated on how it’d be a waste of money for me to watch Chinese theatre because the dialogue would fly over my head. How can I fully immerse myself in the world of the play if I don’t understand what the characters are saying? Yes, I know there are surtitles for most Chinese plays, but that had always felt like a dilution of the art form to me: I would be reading instead of experiencing the play.

But Jun Hong made me reframe my notion of what it means to experience art. Talking to him, I saw that I didn’t necessarily have to understand a show to be in its world, or even enjoy it. After all, some aspects of a performance are indeed universal, as Jun Hong implies when he says that “art itself is a language”—the frozen mask of fear on an actor’s face; the pregnant silence after a character asks a question.

By unduly focusing on the language the characters speak rather than the language of the play, I was only depriving myself of art experiences I would have potentially enjoyed and be challenged by.

That’s how Jun Hong sees our festivals—whether they focus on a particular language, genre of music, or art form.

While he admits that “festivals will attract people already within such circles,” he does not think they are exclusionary. Instead, he says, “festivals are about bringing people together. We’re celebrating the diversity that we have, celebrating what’s special and unique about the field, celebrating each other”.

My eyebrow twitches. While I have no doubt in the sincerity and legitimacy of his sentiments, the argument seems a bit too … PR. You can marshal people to celebrate any number of things: anime, freeze-dried fruit, bubble tea, but that doesn’t make the item inherently worthy of attention or celebration.

Yet, like all enduring clichés, I realise that there is truth in what he says despite its hackneyed quality. As I have discovered for myself—or, to be more accurate, as Jun Hong has helped me discover—a Chinese arts festival like Huayi can have an appeal beyond the cheena or rare bilinguals of Singapore. You just have to find it for yourself.

After all, if even an ang moh pai, a Chinese traitor, an abject D7 sub-pass person like me can find a hook in Huayi, then I’m pretty sure anyone else can.

Huayi 2020, Esplanade’s Chinese Festival of Arts, returns next year. It runs from 31 January to 9 February 2020 and comprises theatre, dance, music, and family-centric programmes.

Is Chinese art obiang or omgz? Demolish us for this terrible sentence at community@ricemedia.co