A recent graduate of Yale-NUS, who was involved in multiple social justice oriented student organisations, was labelled a “sellout” by her friends because she took a job at a large multinational finance organisation—in a diversity and inclusion focused role.

For context, all Yale-NUS students take a course devoted to the science of climate change, as well as read texts critical of capitalism as part of our common curriculum. There are courses that tackle issues through a social justice lens, and plenty of student groups dedicated to social justice in which students can develop their beliefs about how to bring about a more equitable and sustainable world.

As such, the Yale-NUS community is acutely aware of the challenges that climate change, species loss, and wealth inequality may bring.

Many Yale-NUS students come to the conclusion that bringing about the equitable and sustainable world that we need will require significant regulations on most industries and an end to the world’s apparent obsession with profit.

But once they graduate, some of these same students and many other Yale-NUS students still opt for a well-paying job in the corporate world instead of going into academia, advocacy work or other industries that seem to focus on greater goods beyond profit. They compromise on what they thought they valued for money.

In other words, they “sell out”.

Despite having internalised the “sellout” label to a certain degree, this young diversity and inclusion specialist tells me that she feels that she might be doing more good in her current role than if she were at a non-profit organisation (NGO).

In her current role, she has a large degree of freedom to choose programs that she deems suitable. While she’s new to the job, she has already been entrusted with a significant sum to hire a vendor to do unconscious bias training. In contrast, when she interned at an NGO, there were barely enough resources to do multiple programs at once, and so the vast majority of time was spent fundraising—which sometimes meant asking for resources from less than savoury individuals and institutions.

Sometimes she experiences the cognitive dissonance of feeling like she is doing significant good, while also getting paid a high salary in an industry that drives on profit and not charity. However, she believes that for significant change to happen, there needs to be pressure from both inside and outside the corporate world.

Is the term “sellout” even reasonable in this case, or any other for that matter?

While it’s up for debate whether industries like finance or consulting—the behemoth and amorphous fresh-grad-poaching industries that most commonly get associated with the “sellout” label—actually bring more harm than good to the world, it seems clear to me that being in these industries would likely put me in situations that force me to go against my conscience.

One of the most prestigious financial institutions in the world, Goldman Sachs, was instrumental in Malaysia’s 1MDB scandal. The most prestigious consulting firm in the world, McKinsey & Company, helped Purdue Pharmaceutical sell Oxycontin and exacerbate the Opioid epidemic in the United States at the same time as other divisions within McKinsey were publishing reports calling for reform to the Opioid market because of the epidemic.

These clear injustices could not be achieved by one person alone. Dozens, if not hundreds, of people were put in the situation of doing what they knew was immoral or losing their jobs. The vast majority chose the former.

These clearly illegal cases of corporate malpractice that make international headlines are likely only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the moral compromises that some must make in order to keep their job.

Millions of white-collar workers around the world have probably done something for their job that they aren’t proud of. And if I were in the same situation, I would probably do the same.

But just accepting that life is full of moral compromise is no way to move forward, especially when faced with the unprecedented challenges that humanity faces today.

Anthropogenic climate change and anthropogenic species loss both pose extreme levels of existential risks to humanity.

As more reports from bodies like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change get published with increasingly dire predictions, it will become clearer and clearer that business-as-usual is unsustainable.

However, there isn’t exactly a moral imperative pushing people to act, and there are plenty of incentives not to. While governments have the prerogative to regulate industries that harm the environment, why should they hamper their local industry if other countries continue to profit? While the fossil fuel industry has the prerogative to change their business practices and become more sustainable, they risk falling behind their competitors and even failing as companies. While individuals have the ability to whistleblow and leave companies that they know are engaging in unethical practices, why should they endanger their career when no one else is?

I have quite a few friends from Yale-NUS in a similar situation to the diversity officer I mentioned earlier. They plan to go into the corporate world while at the same time caring deeply about environmental issues, wealth inequality and the like. While their stories are not exactly alike—not all of them have been called a “sellout” to their face and some have only been called one in jest—they are all fairly defensive about the label and have many justifications for their choice.

Some of them cite the need to take care of their family financially before worrying about grander issues; others talk about wanting to use the money, prestige, and skills that they might get in the corporate world for greater good down the line.

The reasons for “selling out” are complex and varietous.

While everyone I talked to about this topic had unique perspectives and circumstances, every aspiring or current corporate I spoke to was closely aligned in their beliefs about those who un-ironically use the term “sellout”.

First, they believe those who genuinely label others as “sellouts” are probably hypocrites. The diversity officer shares that while her friends who have labelled her a “sellout” may not themselves be going corporate, they have probably considered doing it.

A Yale-NUS student currently interning at a multinational consulting firm also told me, “I think that a lot of the people who use the term ‘sellout’, if given the opportunity to get a high-paying consulting job, would take it. We are all worried about our own future, and I don’t think that many people in my situation would make a different choice. So, I find the use of terms like ‘sellout’ to be very hypocritical.”

Second, they believe those who shame others for their life choices can only do from a privileged position. For instance, only the high SES can really afford to take a low-paying NGO job, and achieve the moral pulpit that allows them to shame others for their job choices. If they were in a different position, who knows what choices they would make?

It has become blaringly clear to me that using terms like “sellout” and shaming in general are the absolute wrong ways to achieve environmental and social justice.

Today, shaming is used as a tactic in many social justice movements, and it will be easy to just borrow what seems to work for other social justice issues and use it to combat environmental injustice.

That’s a terrible idea. While shaming is a popular tactic in many social justice movements today, it ought not to be—not just because it is mean spirited but also because it’s plain ineffective.

Personally, being shamed only makes me more closed off to others’ perspectives.

Going to college in Singapore, I have been insulated from the sometimes aggressive social justice activism and identity politics that can be found on US college campuses.

However, when I went on a summer study abroad programme to China sponsored by a prestigious US university and was reunited with my fellow countrymen and countrywomen, I experienced a poignant moment where my point of view was attacked because of my identity. I was eating lunch with two Chinese-American classmates, and somehow the conversation was about how Asians are often falsely stereotyped in the United States.

One of the two classmates had a lot to say. It was clear she had a lot of emotional investment in the issue, but that was most of what I could get. She used jargon that I didn’t understand, and the majority of the time, I could not make out her argument.

While I tried to clarify what she meant, my questions didn’t bring me any more understanding. All they did was get her annoyed.

Eventually, she said something along the lines of, “I never have very productive conversations with white people.”

I took that as my cue to leave.

As I was walking away from the table, the first emotion I felt was anger. I was trying to engage in an honest conversation with her, and because she couldn’t convince me of her point, she decided to discount my perspective because of my race. She was tacitly saying, “You’re just another racist white person and you don’t even know it!”

What kind of cheap sophistry is that? Whatever she was saying must have been bullshit.

But as I made my way back from the canteen to the hostel, my anger turned into dismay. If shaming is how the social justice activists of contemporary America try to get their point across, then America is fucked.

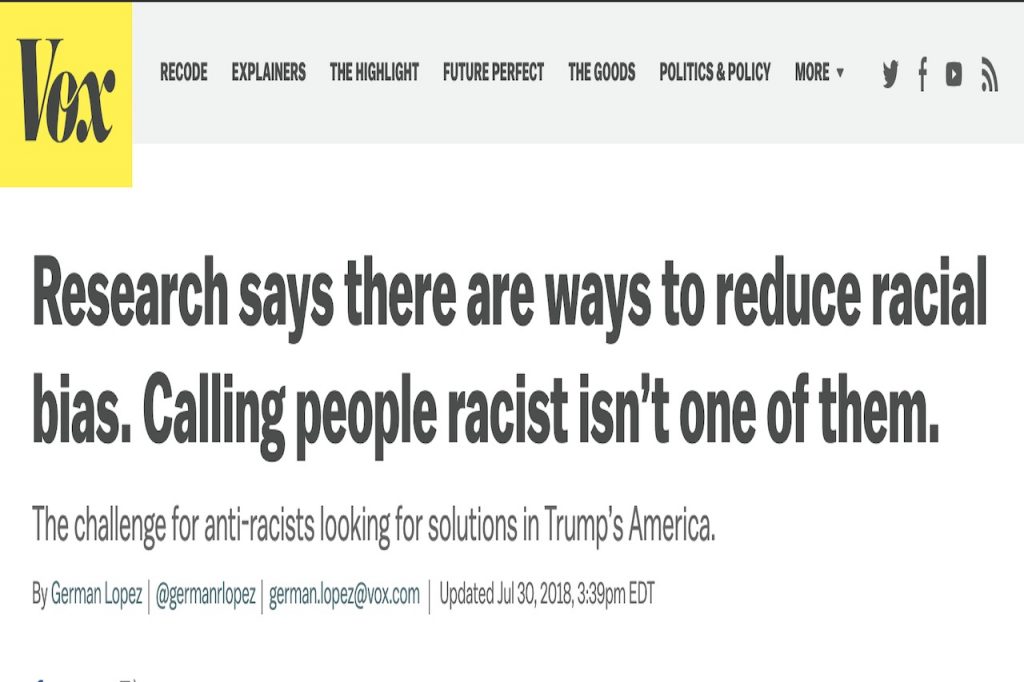

Since that kerfuffle in the Beijing Yuyan Daxue canteen, I read a Vox article by German Guttierez that seemed to vindicate all my intuitions about the counterproductiveness of shaming as a means to achieve social justice. After reviewing various bias reduction studies, and speaking to multiple psychologists about the effects of shaming in political discourse, Guttierez found that shaming is an incredibly poor tool for changing people’s minds.

Instead of shaming, he found honest conversations and the fostering of empathy to be the most effective measure in reducing bigotry and bridging the political gap.

While I wanted to believe that whatever this girl was trying to say was total bullshit, in retrospect I realise that it probably wasn’t. She probably had a legitimate point to make, but when I proved to be an uncharitable interlocutor, her go-to move was to say that my whiteness impeded my ability to understand the truth.

Maybe there is some truth to that; maybe my identity was obstructing my ability to understanding what she was trying to say. I’m not sure.

What I am sure of, though, is that most people would have had a similarly negative reaction if put in the same situation, and that that sort of social justice tactic will get us nowhere.

As the man made existential threats mount, it’s increasingly tempting to try and shame people into doing what we think is right; to call those who willfully join industries that might perpetuate the problem “sellouts” or even worse.

We need to resist that urge. We need to accept that we can’t know for sure what drove someone to their career—they may have needed a high-paying job to support their family and could only get one in a field they found socially questionable; they may have been told that they must go into such an industry by their parents.

Whatever the case, we need to accept that calling someone a “sellout” only serves to vilify and divide.

Instead of looking at the problem as: how do we get the “sellouts” to do the right thing? Activist should instead view the problem as: how do we get normal people to make noble sacrifices for the good of humanity, even when there are so many other things to worry about? How do we get governments, corporations and individuals to make noble sacrifices even when there are so many things telling them not to.

Instead of shaming, we need to have honest and charitable conversations with each other about what it will take to truly tackle these issues. Instead of presenting a false binary of revolutionaries and “sellouts”, we need to show how individuals can incrementally live more ethical and sustainable lifestyles in the modern world.

It only takes two syllables and two brain cells to call someone a “sellout”. But to actually convince them through reason and empathy could require hours of emotional and intellectual labour.

This type of activism that I am proposing is many times more difficult than the most common forms of activism practised today, but no one ever said that saving the world would be easy.

Have you ever been called a sellout? Tell us about it at community@ricemedia.co.