All images by Xue Qi Ow Yeong for RICE Media.

Chinese New Year’s greatest hits have been blaring in supermarkets and malls since Christmas decorations came down. Over the din of frantic last-minute grocery shopping, the volume of the festive celebrations feels almost deafening.

The steamboat pot is out, yusheng dates are locked in, and another round of reunion dinners is upon us. For many, it’s a familiar routine: smiles, small talk, and the quiet dread of navigating family expectations.

But for 28-year-old Benjamin Harris, these gatherings cut deeper. For him, the festive cheer often gives way to uncomfortable reflections about identity and belonging.

Raised as a Chinese Christian, Benjamin is all too familiar with Chinese New Year traditions. As a child, he remembers how his home would be overflowing with relatives. He remembers the sweet snacks and the highly anticipated angbaos.

He did not predict his world turning upside down when, right before enlisting for National Service, he discovered he wasn’t ethnically Chinese. He was Malay.

Benjamin’s story cuts through the veneer of Singapore’s multicultural pride, revealing the fragility of identity in a city that often defines belonging through ethnicity and tradition. In a country where every major festive holiday amplifies a shared national heritage, his experience challenges the foundations of what it means to truly belong.

We grow up speaking native tongues to our families, following rituals and beliefs tightly woven into the race we’re born into. But what happens when the foundations of identity—cultural, emotional, familial—clash with a biological truth we never saw coming?

The Growing Disconnect

For as long as Benjamin could remember, his parents had placed a strong emphasis on a Chinese-Christian upbringing. His parents sent him to a Methodist kindergarten, and they went to church regularly. His grandmother made sure he spoke to her in Hokkien.

“As a child I never questioned my race. My dad didn’t have the typical Chinese name, but I never thought to ask questions.”

His resemblance to his adoptive father also helped his parents keep the charade up.

“We share the same tanned skin and facial features. There was no way I could have figured out that I was Malay,” Benjamin says.

“Maybe another reason why I never questioned my identity as a child was because I never crossed paths with kids of other races. My kindergarten had only two Indian children, and we all followed Chinese and Christian traditions.”

But he did know he was adopted, at least. A relative let slip about it in the midst of a family gathering in 2008, when he was 11. Hoping it was a joke, he looked over at his parents.

He was met with a silent confirmation—he wasn’t his parents’ biological son.

Years later, the additional revelation that Benjamin was an entirely different race than he had been raised to believe plunged him into an existential tailspin.

He would have known much earlier about his true ethnicity if not for his mother. Under the guise of “safe-keeping”, his mum had held onto any form of identification Benjamin had—his Identification Card (IC), his passport, even his birth certificate—and he had been none the wiser about his race.

It was only when he got hold of his IC before enlisting in National Service that he found out the truth.

“In that moment, I no longer felt like I belonged. Looking back, I couldn’t fully process the news at that age, but now I realise how [the news] changed how I viewed anything family-related,” Benjamin shares.

“It made me question whether my entire childhood was a lie.”

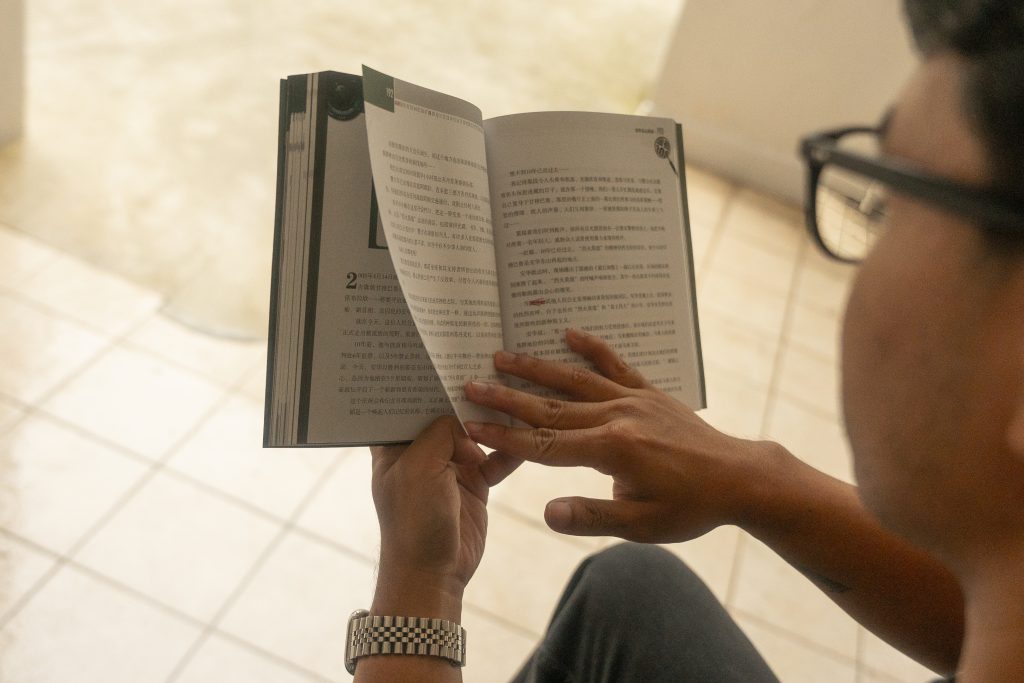

In hindsight, the signs were always there—subtle hints that Benjamin didn’t quite fit in. Nowhere was this clearer than during his years at Nan Hua Secondary, a Special Assistance Plan (SAP) school. Established in 1979, the SAP scheme was created to preserve Chinese-medium schools in Singapore and inculcate traditional Chinese values in students.

In such an environment where the Chinese identity takes centre stage, Benjamin’s experience was far from smooth.

For someone whose parents emphasised the importance of Chinese and Christian traditions since he was a baby, the bullying he faced in school left him feeling disoriented.

He endured microaggressions that chipped away at his ‘Chinese’ identity—taunts like ‘blackie’ and ‘yalam,’ jokes about his skin colour, and the all-too-familiar stereotypes about Malays and their supposed lack of educational achievements.

It instilled self-doubt about his identity. And by the time he completed secondary school, he found himself identifying less with his Chinese upbringing. Still, he never considered the possibility that he was anything other than Chinese.

As it turned out, his parents had been hiding more than they let on. When his parents married, his father converted from Islam to Christianity. For that, he was disowned by his Malay-Muslim family. To avoid the shadows of his past, Benjamin’s dad also changed his name.

It was the missing piece of the puzzle. Finally, Benjamin realised why his parents never spoke to him about his race. Benjamin’s dad never introduced him to Malay culture. Instead, he continued raising his son as a Chinese-Christian.

“Being told you’re one race and finding out you’re another is very jarring. Growing up thinking I was Chinese and then finding out I was Malay. But in actual fact, I can’t really say I belong to either,” Benjamin says.

While it might seem liberating to move between being seen as Chinese, Malay, or mixed-race, racial passing often brings a deep sense of disconnection. For Benjamin, it led to a profound alienation—his perceived identity clashed with the one he’d internalised. The world viewed him through the lens of his biological race, one he knew little about and struggled to reconcile with.

There’s an underlying assumption that cultural authenticity is tied to one’s racial or ethnic background. For an adoptee in a cross-cultural adoption, questions of authenticity are exacerbated.

What makes you Chinese if your parents don’t speak a word of Mandarin or dialect, and you can barely order cai fan without tripping over your words? Or are you not Malay if Malay cuisine isn’t your comfort food and your Bahasa Melayu is more guesswork than fluent conversation?

Can you truly claim a cultural identity if you don’t share the same genetic history or lived the experiences of those deeply immersed in it?

Who Am I?

During his identity crisis, Benjamin distanced himself from his parents, indirectly blaming them for feeling this way.

“How do you reconcile the fact that you’ve been fully immersed in the Chinese-majority experience, but your genetic heritage doesn’t match the racial identity you’ve been assigned by society?” he asks wearily.

Gradually, his family dinners faded away and became a thing of Benjamin’s childhood. He can’t remember exactly when, but his extended family stopped coming over, citing that they were busy with other commitments. The spot where Benjamin’s family placed their Christmas tree each year was soon replaced with piles of boxes.

When his grandmother fell ill, the festivities stopped altogether. Chinese New Year now meant staying in his room, a far cry from the times of loud, carefree laughter he once shared with his cousins.

The comfort and familiarity he used to find in his family’s cultural celebrations turned into reminders of his ethnicity limbo—an unusual feeling of isolation that not many can ever relate to.

The impact of his identity crisis manifested outward. The walls of his home, where Chinese New Year decorations once hung, are now marked with patches of dried-up Blu Tack. The family photos that once sat proudly in front of the television have disappeared, tucked away in a file cabinet.

Aside from Benjamin’s room, the house betrays no trace that a child ever grew up there. It’s as if his childhood presence has been erased.

To Benjamin, it’s a clean slate.

Weighed down by unspoken emotions, his relationship with his family remains tense. Time and again, Benjamin found himself wondering if his adoptive parents ever truly wanted him—especially when their emotional presence felt distant, if not entirely absent.

“We didn’t spend much quality time together. Yes, they invested a lot of material and financial resources, but nothing emotionally. It made me think then, why did they even adopt me, you know? It made me very disillusioned with family,” Benjamin sighs.

Although part of him wishes his dad would share his experiences with Malay culture, Benjamin fears it might unravel the identity he’s painstakingly rebuilt. This fear also explains why he has no interest in finding his biological parents—he doesn’t want to risk destabilising the life he’s created.

Instead, he chooses to view his ethnic identity in a different light: as a journey to reinterpret the cultural narratives imposed by Singapore’s rigid racial checkboxes.

“I’m lucky, I guess. In a sense, I get to carve out an authentic sense of self that is not determined by the ethnic status quo society is obsessed with,” he offers.

“I can be just Benjamin—the guy who’s adopted, wears a copious amount of batik shirts, and isn’t one race or the other. I’m both. I’m comfortable now, knowing that I can be as fluid as I want. It’s liberating, and it’s a chance to leave my past behind.”

Redefining Culture

Despite his estranged relationship with his adoptive parents, Benjamin isn’t in a rush to figure out his past or find answers. Instead, he’s trying to find a balance between the culture he grew up in and the one he never had experience with.

Most of his time is spent finding ways to understand Malay culture by volunteering with advocacy group Lepak Conversations, learning Bahasa Melayu, and spending Hari Raya celebrations at his Malay friends’ houses.

He also spends his Chinese New Year and Christmas holidays with his partner and her family or his group of friends. This year, he’s choosing to enjoy a reunion dinner with his partner’s family before flying off on a solo getaway to Bali right after.

For him, these celebratory gatherings are simply markers of public holidays—there’s always the feeling that it’s someone else’s cultural commemoration.

This sense of disconnection isn’t unique to Benjamin—it’s a struggle many of us know too well. Even when we’re immersed in our culture or confident in our ethnic identity, there’s often a lingering feeling that we’re on the outside looking in. We go through the motions, understanding the traditions but not fully embracing them.

Why do the very rituals meant to define us sometimes feel so hollow?

Perhaps it’s because, over time, these traditions have become more about obligation than meaning. The more we conform out of obligation to family or society, the more we lose sight of what those rituals should signify.

This detachment highlights how we’re caught between two worlds: the heritage we’re born into and the one we’re actively trying to create for ourselves. In Singapore, cultural continuity is not a given, especially in a multicultural society where identities and values evolve over time. Instead, it’s something we wrestle with, reshape, and ultimately redefine.

Maybe belonging isn’t about perfectly fitting into these traditions. It’s about reclaiming them—adapting them to reflect who we truly are. Authentic connection doesn’t come from blindly following the past but from reimagining it to match our ever-changing selves.

That’s how we claim ownership of our stories just like Benjamin—and maybe, in the process, we finally feel like we belong.