All images by Stephanie Lee for RICE Media unless stated otherwise.

Bryan Yap, a high fashion model, sashays down an open stretch in an industrial car park with yellow and blue plastic containers in tow.

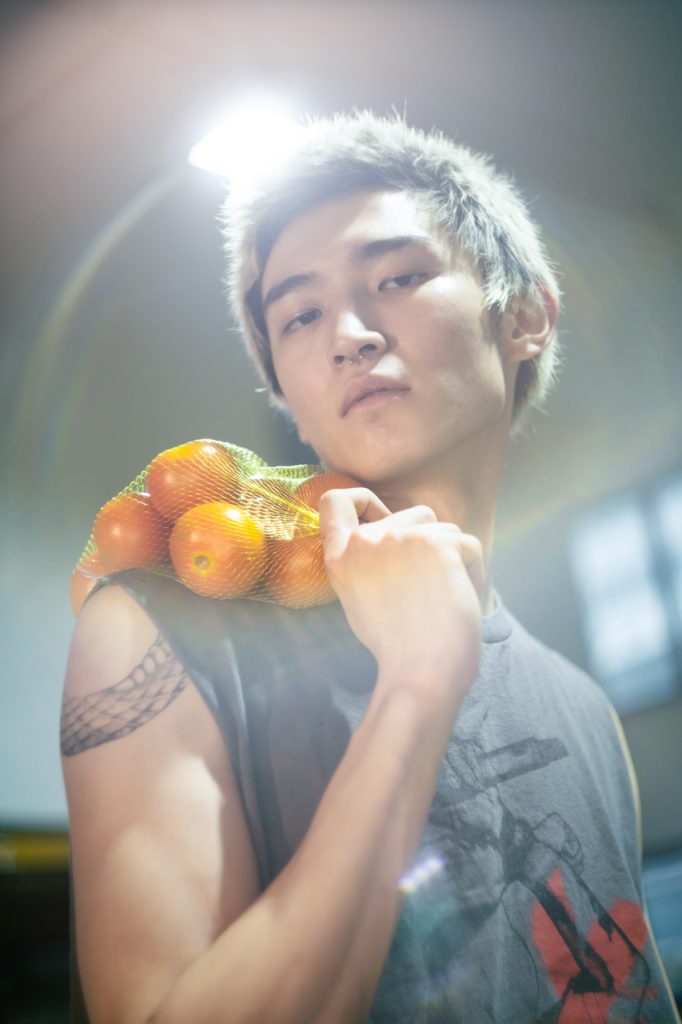

With his blonde hair and sharp jawlines, one might assume the lithe 25-year-old is walking down the runway as part of a factory-themed fashion show (Derelicte!). His Instagram account documents his life as a model, so you’d be forgiven for thinking so.

An adoring crowd is nowhere to be seen. The flashes from cameras are missing. Snooty high-fashion journalists are absent; they wouldn’t be caught dead in an industrial car park in Sembawang.

There is no runway. Bryan is just starting his shift as a vegetable vendor.

Lettuce Begin

It’s still early in his shift, but he has already worked up a sweat. The industrial fan does little to cool Bryan down.

A black cotton singlet is a wise choice for his OOTD. Damp as it is with perspiration, it conceals the sweat stains.

Unfortunately, the singlet can only do so much to hide the fact that Bryan is sweating like an igloo in an oven. He pauses occasionally to find a towel to dry himself off, away from the produce. A strong, earthy odour permeates the warehouse.

The unremarkable grey of the warehouse we’re in is dotted with vibrant colours—red chillies splayed over old newspapers, green limes packed neatly in plastic bags, and orange carrots lined across the warehouse’s many metal shelves.

The vegetables are sourced from farms in Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand. After which, they are delivered to Bryan. He packs the vegetables and sends them off to his customers.

His family business, Ah Phoon Vegetable Supplier, supplies vegetables to 40 clients across the island. His customers range from stalls in shopping mall food courts—mostly chicken rice stalls—to office kitchens.

Vegetables occupy most of the space before being loaded into empty plastic containers for his customers. His girlfriend, 24-year-old Kaci Beh, runs down a client’s order list. He squeezes past her to get to a packet of onions.

A plastic container smacks the cement floor with a soulless thud. He has 20 more orders, and that means 20 more plastic containers to fill.

Once packed, the containers are moved to the pickup area. Delivery vans will arrive early tomorrow morning to distribute the vegetables.

The Duality of Clothes and Cabbages

When Bryan is not arranging onions, he spends his time posing in front of the camera in air-conditioned photography studios. Selling vegetables is Bryan’s day job; he also works as a fashion model under the modelling agency Now Model Management.

“I didn’t grow up thinking I wanted to be a model,” Bryan explains while counting a row of cabbages.

“My mum used to be a model. She showed her old model colleagues a family photo, and they suggested I try.”

That was in 2015, eight years ago. At the time, Bryan was preparing for his ‘N’ Levels. After getting his first modelling job when he was 16, he is now a second-generation model in his family.

“My mum told me to take it as a part-time job if I wanted to try it out, and I did.”

Being a model has its perks. He also admits he gets to wear clothes he can’t afford to buy himself.

Supplying vegetables, like modelling, is something he inherited from his parents. His family have been in the business of vegetables for over 20 years.

His grandfather started Ah Phoon Vegetable Supplier over 20 years ago before his father took over the reins in 2006. Bryan, having joined in 2022, is a third-generation vegetable vendor.

“I could have gone to polytechnic after I served National Service, but I felt a bit old. I only have one ITE certificate. In Singapore, it’s hard to go far with that certificate. I was lucky that my family supplied vegetables as a business,” Bryan remarks.

The last packet of vegetables is loaded into the container. Kaci, also a fashion model, scans through the following list containing an order of chillies. She puts on plastic gloves, finds a stool, and sorts chillies into a plastic bag.

Bryan walks over to a shelf lined with cabbages. “Before we had this warehouse space, we supplied vegetables from our home. We had a cold room in front of the house and packed the vegetables in the front yard. It never occurred to me that I would grow up to do this.”

He stepped into both of his trades by serendipity. While loading cabbages into the next container, he admits he dreamed of being a car mechanic. It’s what led him to pursue mechanical engineering as his Higher Nitec course.

“Mechanical engineering. Mechanic,” he reiterates, emphasising the word ‘mechanic’.

“I wanted to fix car engines. But I didn’t see any engines in two years,” he chuckles.

Runway and Reality

The business runs on three employees: Bryan and his parents. Four, if Kaci finds time in her schedule to help.

A typical day for Bryan starts in the late afternoon, around 4 PM, and ends at 9 PM at night. He supplies vegetables six days a week, with an off day on Saturday.

Unless Bryan is booked for a shoot, that is.

“The benefit of working as a vegetable vendor is the flexible schedule. If I have a shoot that day, I’ll take an off day and work on Saturday instead. My parents know that I’m handling two jobs. They have been very supportive,” Bryan says.

“My parents told me I’m young and should enjoy myself on my off days while I still can.”

He quickly scans the warehouse before admitting he’s thankful for his off days and shoots. They’re a break from the monotony of packing vegetables. Being surrounded by vegetables in a Sembawang warehouse can be quite isolating and lonely, he admits. Photo shoots and fashion shows allow him to meet new people—a nice change of pace.

Unfortunately, he doesn’t have as many modelling jobs as he would like. He gets an average of four to six modelling jobs monthly, so being a full-time male model is not financially viable. He hesitates when asked how much he earns as a model.

“Unless you make it overseas, it’s just like working in any other job,” he answers sheepishly. The question distracts him. While packing xiao bai cai into a plastic bag, his hands fumble over the vegetables.

“In Singapore, guys don’t get as many modelling jobs as girls. You don’t have to be a model to understand that.”

The demographics for fashion models in Singapore have yet to be made available. In the United States, however, only 22 percent of professional fashion models are men.

In Singapore, a male fashion model earns about four percent less than a female counterpart.

Female models earn an average of $88,480 yearly. Male models, on the other hand, make a yearly keep of $84,740 on average. Of course, a male fashion model’s salary depends on their popularity and whether they’re modelling full-time.

Like vegetables, models also have a limited shelf life. He shares that models struggle to confront the inevitable end of their careers once they hit 30.

“There is always someone younger who wants to take your place. I’ve met models as young as 16, and I feel old.”

Bryan is only 25.

“Commercial models, people with a gentler look, get more jobs,” he explains. “I’m more of a fashion model because I look like this. I look more fierce,” he explains. His gaze stays fixed on the carrots before him.

His nonchalant demeanour betrays his stoic glare. Fierce look or not, he seems as if he’s perpetually posing for an invisible camera, even while packing vegetables.

For Bryan, his biggest challenge is the competition for limited jobs. It means that he has to contend with other career options if his modelling opportunities run dry. Good things can only last for so long.

Behind The Scenes, Beyond The Labels

While models look to continue their post-modelling careers in other ways (in front or behind the camera, mostly), Bryan sees supplying vegetables as his long-term career.

“This is my career already,” he asserts. He intends to continue the family business when his parents retire.

That said, Bryan still hopes to take his modelling career as far as possible—he doesn’t take the opportunity to be a high fashion model for granted. He travelled to London and Milan this month to look for an agency to represent him overseas.

“Doing an overseas show, that’s my dream. But we’ll see.”

The xiao bai cai are finally packed. It takes a good five minutes to complete the task. Surprisingly, packing xiao bai cai is trickier than one might think. These unassuming greens are a big headache for vegetable vendors, Bryan shares.

Xiao bai cai must be packed in a specific order—line by line, with the sturdiest ones at the bottom of the plastic bag. A haphazard arrangement spells disaster. The plastic bag might topple, and any vegetable that makes contact with the ground goes straight into the bin and cannot be delivered to customers.

Trade-specific knowledge (like how to efficiently pack xiao bai cai in a plastic bag) often goes unseen. At first glance, Bryan’s chosen trade seems easy enough—chuck vegetables into an empty plastic container and move on to the next.

Yet, sifting through chillies, lemons, and leafy greens requires deft hands and sharp eyes. Our admiration of knowledge-based or creative work makes it easy to undervalue the skills in blue-collar jobs.

The risks involved in blue-collar work are often forgotten. For Bryan and his family, their fortunes lie in Mother Nature’s hands. An unexpected rainy season means a drop in yield and more expensive vegetables when they reach Singapore. The last time this happened was in December last year.

Customers could easily switch to other vegetable vendors offering more competitive prices at the slightest hint of a price increase—over 900 wholesalers of fresh fruits and vegetables show up after cursory research in the Singapore business directory.

According to a 2022 Institute of Policy Studies survey, blue-collar workers feel that certain forms of work are preferred over others. They could find their work less valuable than white-collar professions.

Those who make a living through manual labour may have “internalised society’s lower valuation of their work,” says organisational psychologist Brandon Koh to The Straits Times.

Only about half of these ‘essential workers’ during the pandemic said their career was meaningful and saw their work as having a positive difference.

It’s a worrying trend, especially when a sense of purpose at work is linked to health, like a lower risk of heart disease and stroke. A lack of purpose also opens dangerous doors to substance abuse as a form of escapism.

Carrots and Courage

Bryan is a role model in tackling the stigma surrounding blue-collar workers. One might expect high-fashion models to live their everyday lives in secret. After all, a public image of glitz and glamour is a model’s social currency.

His TikTok account, which documents his journey as both vegetable vendor and model, are bold proclamations for the contrary.

“I don’t need people who will treat me differently based on my job. I want people who genuinely accept me for who I am. Don’t judge people based on their job. As long as you’re doing honest work and not hurting anybody, that’s good enough.”

So far, Bryan is fortunate to have fashionable friends who accept his life as a vegetable vendor. They even occasionally hang out at his warehouse.

Workers from the office space opposite his warehouse are knocking off. Bryan has 13 more empty containers to pack before he can call it a day. It will be another three hours before he leaves.

“Nice car, nice house, nice watch. My father told me that when I was young. If I have all three, I’ll be successful,” he recites.

“I don’t mind working hard in my 20s. When I am in my 40s, I will relax. I am fighting to provide a good life for myself later on.”

Bryan turns his attention to a corner of the warehouse filled with plastic bags of vegetables. The unmistakable rustle of plastic bags erupts. The xiao bai cai have collapsed among themselves. He sighs and walks over.

He sorts through the vegetables again before pausing to towel off sweat. The worlds of high fashion and vegetable wholesaling couldn’t be any more different. Bryan, however, sees little difference between the two realms.

Superficialities aside, they’re both demanding jobs. But Bryan knows where his core identity lies.

“When people ask me what I do, I tell them I am a vegetable vendor first.”