All images by Nicky Loh for RICE Media

At this moment in time, we’re still in the full-swing festive sprawl that is Chinese New Year. Spirits are (generally) high, bellies are mostly full.

But the spectre of impending change looms large over what counts as celebrations under the auspices of the ever-evolving new normal.

ADVERTISEMENT

On February 18, Finance Minister Lawrence Wong will lift the curtain on Budget 2022. Therein lies the details about an impending Goods and Services Tax (GST) increase from 7 percent to 9 percent.

In his annual New Year Message, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong revealed that, for the health of the economy, the government has to enforce certain measures that would frame the year ahead as a “time of transition”.

“It needs to raise additional revenues to fund the expansion of our healthcare system and support schemes for older Singaporeans. Those who are better off should contribute a larger share, but everyone needs to shoulder at least a small part of the burden,” he said, outlining in broad strokes the government’s approach.

That “small part of the burden”: is quantified by the 2 percent GST hike and will result in an across-the-board increase in the prices of goods and services. Everything is about to become that much pricier.

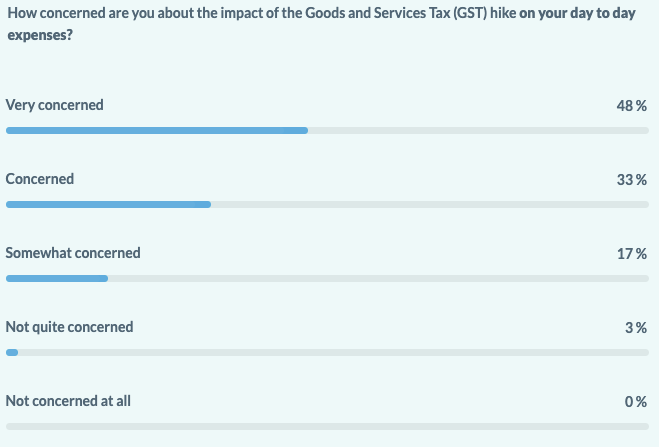

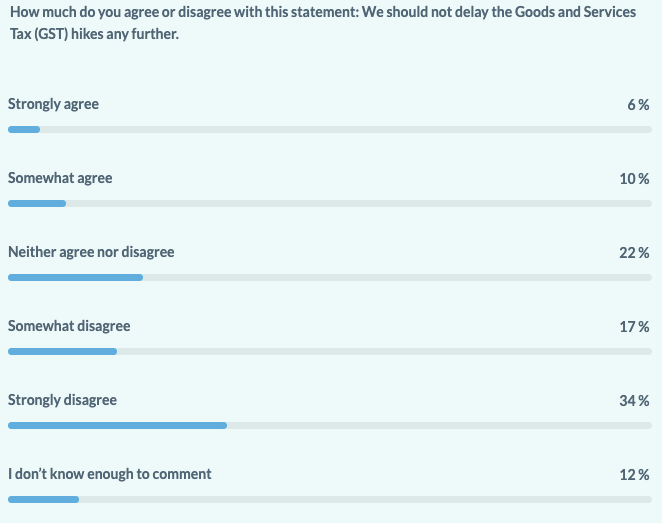

Are Singaporeans cool with it? According to a survey we recently conducted with independent research company Milieu Insight, the results speak for themselves.

43 percent indicated that they were aware of the reasons for the hike, while 45 percent stated that they weren’t totally sure of why it was happening. 33 percent of the respondents indicated that they were “very unsupportive” of it, with an additional 25 percent stating they were “somewhat unsupportive”.

This sentiment corresponds tellingly with how Lim* and Alvin Tan, two minimart operators, feel about how it’ll impact their businesses and livelihoods.

ADVERTISEMENT

Make no mistake: There’s no upside, they say.

Good Intentions Will Be Tested

Lim, 52, is the owner of Amour Minimart, a cosy store that has been operating along Bedok North Road for over three years. Extremely affable and perpetually smiley, the man is a beloved figure in the neighbourhood.

His shop is flanked on all sides by HBD blocks that paint a convincing picture of the platonic HeartlandTM long advertised in the Singaporean consciousness. Mothers and grandmothers accompany boisterous toddlers. Teenagers with messenger bags stand in corners texting until their friends arrive. All this happens against a backdrop of streaky variations of grey and white – the default void deck palette.

But in this almost utilitarian setting, life convenes around the minimart. On multiple occasions throughout our conversation with Lim, residents and customers wave at him as they pass the shop. I get the feeling that it’s my presence, along with my notepad and recorder, that stop them from conversing with him like they usually would.

The contrast between his operation and Alvin Tan’s is stark. The 31-year-old son of the owners of Kim Eng Mini Supermarket assists his parents in running a business that will be operating for 20 years come July this year. The establishment leverages on social media marketing and mobile commerce. By all accounts, it’s a bigger and more sophisticated operation than that of the typical convenience store

But even though the latter’s operation is more comprehensive and sizable than the former’s, the spirit behind both endeavours remain the same.

When asked why he opened a minimart after being in the construction industry before, Lim offers a touching answer. “We were semi-retired at that point in time. But we wanted to give back to the community here. People work hard. They should have some conveniences at hand”.

Likewise motivated by community, Alvin responds with, “I’m ultimately caring for my customers”. He reveals that he’s situated in a “very old, very mature estate” where a sizable number of his customers are people between 60 to 90 years old.

From his observations over time, he gleans that his regulars “don’t buy that much because they don’t have the spending power”.

“They also don’t eat that much. It’s all about convenience for them”. They frequent his shop because it’s close to where they live and his pricing suits their budget for daily necessities.

The word ‘convenience’, however, might not be apropos once the revelations of Budget 2022 are enacted. The altruism of both men and their fellow small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) operators will face a reckoning with far-reaching implications for their livelihoods and their customers.

As if to punctuate what’s at stake at the close of my conversation with Lim, a child picked up a chocolate bar from his shop and held it up to him. His mother asked if she could pay for it the next day, to which Lim smiled kindly and waved them off.

Price is Everything

“On one side, there’s NTUC Fairprice. On the other, there’s Cheers. In between, there’re so many minimarts,” Lim sighs. This is the arena in which the store owner does battle daily.

He outlines his challenges as such: “I cannot expand much because I only serve the neighbourhood. There are also bigger marketplaces. With the competition of pricing being what it is, I feel that smaller businesses like ours are being phased out. Retail is tough. It all depends on your luck”.

He reveals that he currently draws a monthly income of about $1,500, a humble amount enough for him to make do with.

The might of retail giants is also felt by Alvin, despite his operation being considerably bigger than Lim’s.

“If Giant, for example, were to continue their current way of marketing — which is very price-competitive — we will lose quite a few customers to them,” notes Alvin.

Both concede that price is key to their operation of convenience stores. But the price of competition is set to be more unsparing than it currently is.

Already, the odds are stacked against them. Lim volunteers: “The problem is, when bigger businesses have offers on the same items that you sell, you’ll start to get a bad reputation. They win on quantity. Once, I priced cup noodles that cost $1.40 at $1.60. Then, the bigger firms had an offer for the same product at $0.50. That’s why it’s very difficult for SMEs, especially minimarts, to survive”.

He also contends that bigger companies and MNCs have the strength and wherewithal to absorb the aftershocks of the hike, while most SMEs don’t.

Lim offers a damning example of how this plays out via the GST-registered companies scheme, which allows for such companies to claim GST rebates. Here’s the kicker: To even qualify, said company’s taxable income must be or is anticipated to be “$1 million”.

A far-reaching price hike, such as the one to come, is poised to have devastating consequences on SMEs like the two profiled here. But, as Alvin sees it, “lower-to-middle income groups will get the first knock of the hammer. If they can’t afford the hike, they will hold back their expenditure”. Those who are savvy to the more competitive prices touted by the bigger players will then flock there.

Even though he laughs when he says it, Lim paints a grim picture of the fate of business-owners such as himself: “What other options are there? Do Grab or foodpanda?”

Convenient Vices

Cigarettes and alcohol are in the class of goods whose price increase will affect consumers most tangibly. As it stands, minimarts make a sizeable income from those products alone.

For Lim, cigarettes account for 40 percent of his total revenue. They also hold a spillover effect: customers who come to him for cigarettes also end up purchasing other goods, such as drinks and/or snacks, in most cases. And while Alvin declines to state how much tobacco and alcohol sales contribute to his revenue, he says that the industry trend for a business of that size is roughly between 50 to 60 percent.

This means that the takings from a significant revenue-generator for convenience stores are about to be deeply impacted.

But come what may, Lim reveals that, once again, the playing field is uneven.

Good times or bad, people will never stop stretching their dollars. In this chaotic battleground, whoever wields the cheapest price wins. Price-savvy consumers who have no qualms about purchasing contraband tobacco or finding illicit alternatives might well switch to sources that can give them what they want at a price they deem reasonable. This is well-poised to threaten legitimate businesses.

Illicit trade is exacerbated by the fact that the government currently levies the third-highest tobacco burden in the region, taxing a specific tax rate of $0.427 per stick. The 9 percent GST hike is an additional overlay to that. Existing as they do within this volatile framework, Lim and Alvin guarantee that they will lose customers to entities — both legal and illegal — with the cheapest options.

The Floodgates Will Open

In any case, “revenue will drop”. Going by the math, it seems almost inevitable.

It’s simple physics: Every action begets a reaction. It’s no secret that alternatives to cigarettes, most visibly in the form of vapes, are already available in the local black market.

They appear to be in wide circulation, though the government has classed them as outlawed goods. With the implementation of the proposed hike, it seems likely that they will rise to be attractive — if dangerous — substitutes for now-even-higher-priced cigarettes.

Lim and Alvin concur that smokers will either reduce the frequency of their cigarette purchases or find their way to vapes if they can’t afford the habit.

“When they can’t get their vape pods, what will they buy? Cigarettes. Even then, if they want to buy cigarettes, they’ll go to the cheapest, if not, cheaper, source. The reason they’re vaping in the first place is because it’s cheaper than cigarettes”, explains Lim.

Whether vapes take over the market en masse remains to be seen. But given the current climate, their appeal appears to be more inviting than ever.

A Resounding No

The general antipathy towards the GST hike is universal. Frustration about its imminence is a given in any conversation about it.

Like many others, Lim is patently against it: “Big companies won’t be impacted as much as us. They can make back everything. For small businesses, it’s not that easy. Lower-income groups get a $100 GST rebate. What is that going to do?”

Alvin initially conceded that if the country needs money, there’s not much we can do to prevent a hike from happening. But from a business standpoint, he does admit that it might be a bad move to implement it so soon.

“Never during a pandemic”, he affirms, subsequently citing the popular local meme of the people being given a drumstick only to be asked for a whole chicken in return.

At present, rebates are available to cushion the impact of the price surge. But there’s a prevailing feeling that they are a temporary panacea for a deeper, infinitely longer-lasting development.

There is a more meaningful, less harsh alternative to the GST hike for both men. They’d like the government to listen to, address, and cater for the concerns of SMEs before resorting to raising prices across the board.

As Alvin sees it, the government should consult small business owners like him.

“There are so many small businesses in Singapore, not just MNCs. We need to have some input. MNCs can afford such hikes in the first place. So, these hikes will come at the expense of SMEs.”

Equality, not equity, is the lens through which this issue should be addressed, according to SMEs. Come February 18, we’ll know how much we’ll have to tighten our bootstraps.

In the interim, relish the 7 percent while you can.