Two days later, AFP obtained the near-final draft of a landmark United Nations report about the state of nature and biodiversity. It comprised a grim summary of the ongoing Anthropocene (i.e. current) extinction event, and how it’s going to take us out along with it. The report is now out, and you can read a summary of the findings here.

But if you ask most Singaporeans what they think about climate change, they’ll likely shrug their shoulders and give a disyllabic, dismissive response:

“It’s bad.”

The very fact that you bothered to click on this article demonstrates that you have some measure of interest in the issue. For most Singaporeans, however, global warming simply means wetter monsoons, hotter dry seasons, more flash floods, and the perpetual islander’s fear: rising seas.

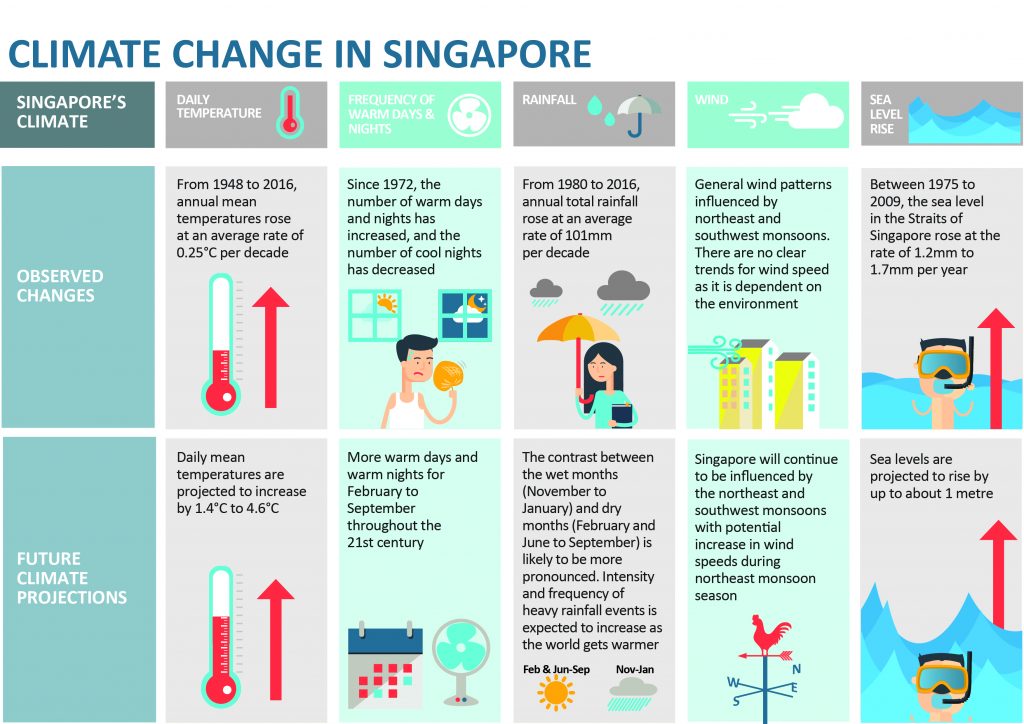

Heading over to the National Climate Change Secretary (NCCS) website yields a similar weather-based result. If you’re like me, and are disinclined to peruse government verbiage, you’ll skip right to the infographics portion of the page:

That’s it?

All these problems seem abstract and far away. After all, we have until 2050 to go carbon neutral—or was it 2040?

Aren’t there more pressing things to be concerned about? What’s the need for an emergency?

Two words: feedback loops.

Here’s an example: global warming is causing polar permafrost to melt rapidly. Permafrost contains methane, a pollutant present in cow farts and 34 times as potent as carbon dioxide. When the methane is released, more pollutants in the atmosphere result in more global warming, more permafrost melting, more pollutants, and so on and so forth.

If you think it’s just about ice, consider this: the oceans are one of the biggest carbon sinks out there, and studies as early as 2011 showed that when oceans get warmer, they release more and more carbon dioxide. More pollutants mean more global warming, more ocean warming, and more pollutants being released. You get the idea.

A little global warming today, caused directly by human-emitted pollutants, results in much more global warming in the future.

As the planet warms, the weather becomes more unstable. Internationally, food security is threatened by drought, flooding, and natural disasters. Fish eggs boil in the seas; crops wither and die in the heat.

Can we live with taller mercury, bigger droplets, worse gusts, and bulging waves? Yes.

Can we keep going when the shelves run dry? No.

Singapore is a city-state, which means we have nowhere to turn to for vast farmlands and essential crops.

Essentially, feedback loops ensure that our present actions determine whether we see the collapse of human civilisation in the next decade.

“If it doesn’t impact them directly, people just don’t care,” says one friend, even as he acknowledges fears over melting permafrost releasing deadly plagues.

“People want what they want,” says another. “There’s nothing we can do.”

Climate apathy is not a problem restricted to Singapore. Many human cognitive and emotional biases, baked in from our hunter-gatherer days, cripple our ability to respond adequately to the threat.

For one, optimism bias powers our will to survive against adversity, and will not let us fully appreciate the whopping scale of the oncoming catastrophe. Secondly, our short-termism makes us properly categorise our problems in order of urgency, preventing us from tackling the leaky pipe that drips today but explodes in a decade.

Perhaps the problem of apathy is even more significant in Singapore, where we are already (internally) renowned for our political indifference. After all, we are accustomed to an efficient, productive, and transparent government.

But there are issues that every Singaporean cares about and campaigns for, knowingly or unknowingly. We do this in every private conversation, over a disposable can of beer or cider; over styrofoam packets of chicken rice and kway teow.

Return my CPF. Pay ministers less. Stop hiring generals. Train breakdown.

The two key aspects of these bread-and-kaya issues are an identifiable enemy, and/or a daily effect on Singaporeans’ lives: CPF makes you poorer, PM Lee earns too much, Desmond Kuek trashed SMRT, I’m going to be late for work again, shit.

Overall, global warming is a double-blind issue: we can’t identify one clear guilty party, and we can’t identify one clear Singaporean victim. This ambiguity only heightens our inability to come to grips with global warming on a daily basis.

For the more activism-inclined, and those who acknowledge the presence of global warming but don’t seem to care enough, perhaps the only way forward is to rely on our own human networks. These include friends, lovers, parents, siblings; people whose opinions (rightly or wrongly) are given drastically more weight than those from a minister, a climate scientist raving about GHGs, or an internet writer rambling about the end of the world.

Let me put it this way: if you care about your children, your younger siblings, your nephew, your niece, you owe it to them to find out more. Read up on global warming, on Singapore’s impact as a country, and on your impact as a consumer. Then get the word out.

Tides are changing. A survey this April found that, among caring for their parents and other social causes, the environment was an important issue to millennial Singaporeans.

But it’s hard to tell if they are simply paying lip service. Are young people prepared to sacrifice the life they know to preserve the future?

And even if they’re serious, millennials do not make up a large portion of Singapore’s population.

So the question remains: do older (and younger) Singaporeans care enough about global warming to spur the government to take stronger action by divesting from carbon-producing industries, drastically limiting consumption and waste, and committing to a less comfortable, carbon-neutral future?

Local media has a large role to play in this discussion. It’s very easy to just sit back and roll the tapes on Asia’s Strangest Home Videos. Perhaps news channels could, instead of devoting the last 5-10 minutes of their nightly broadcast to dash-cam fight footage or cute animals, commit that time to remind us of the impending catastrophe—and what we should be doing about it.

A democratic government acts on the will and awareness of the people. So let’s be aware, and spread the word. We are two minutes to midnight; half a degree shy; 12 years away from the climate catastrophe. The least we can do is talk about it.