Top image: Photo by Piron Guillaume on Unsplash

The work of a Child Life Therapist is an interesting one. While we are quick to offer sympathy and empathy when we see children needing surgery, we tend to overlook the psychological pre-operation aspect of the procedure. Still, it’s not as if we’re entirely unaware of the stresses children feel before undergoing any medical process. Consider the many things parents resort to when pacifying a child before an injection or medical treatment—sweet treats, toys, McDonald’s Happy Meal, or even iPad time.

Beyond routine vaccinations, also consider children who are undergoing invasive surgery for more severe ailments. That trepidation we feel hours before such operations? Take that and multiply it by a child’s mental acuity that’s underdeveloped and often binary. It’s either painful or not. You get better, or you die.

“I remember the look of anguish on a 7-year-old boy I worked with,” Nur Shazalyn Abdullah, a Child Life Therapist shared.

“When I asked what was bothering him, he said he was dying. Upon further probing, I realised then that he had this huge misconception. He thought he was on the brink of death because an IV plug was attached to his hand.”

Child Life Therapists like Shazalyn play a crucial role in reducing traumatic healthcare experiences that children may face and correcting possible misconceptions they have about receiving treatment and staying in hospitals.

Before joining the Khoo Teck Puat – National University Children’s Medical Institute at National University Hospital as a Child Life Therapist, Shazalyn worked as an early childhood educator. Her love for working with children, combined with a deep interest in the healthcare sector, lent itself naturally to her current calling as a CLT.

In her line of work, she saw how important it was to normalise and empower children to cope with anxiety-provoking, daunting experiences in hospitals. It is also crucial to educate children on the medical tools and their specific uses so that they are familiar with them—what are they for, and how will they help them get better?

The work of a Child Life Therapist

Many children may think that doctors and nurses are there to hurt them because of the medical tools and equipment used. As a result, behavioural issues often arise due to their fears and anxieties.

For example, children may refuse to comply with certain medical procedures because they are fearful of needles and the “scary-looking” MRI machine that looks like it may “swallow them whole.”

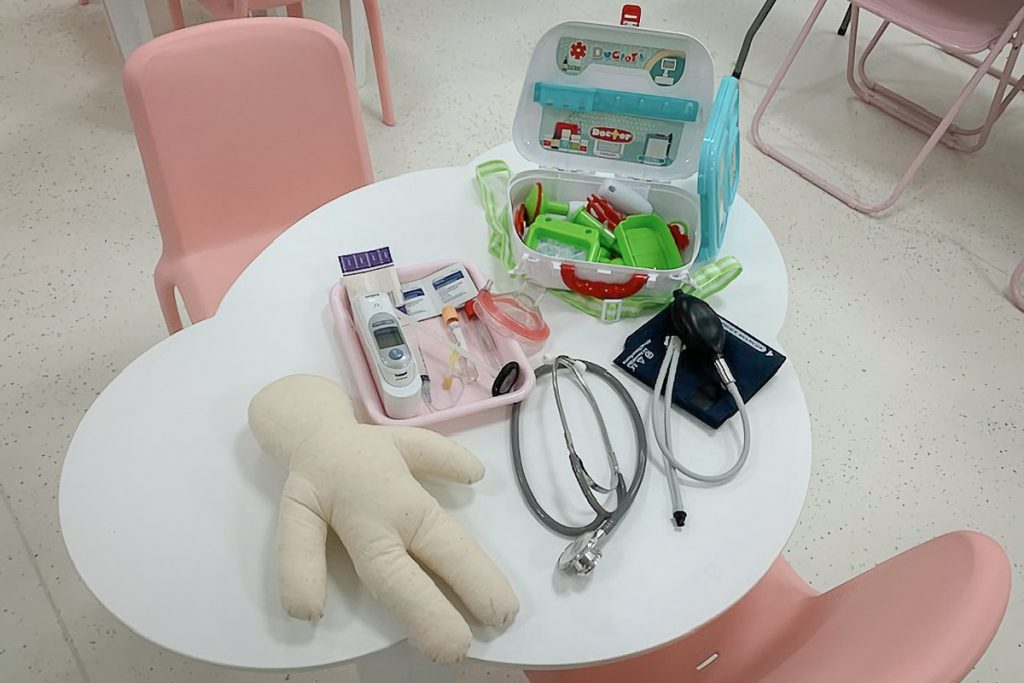

To help children understand why they are in the hospital and what is happening to them, Shazalyn uses role-play, social stories, and calico dolls to better connect with them.

Calico dolls are made of plain fabric stuffed with polyester fibre fill. Children create their unique dolls by drawing on them using felt tip pens. These dolls then become their steadfast companions as they undergo a particular procedure, for instance, IV insertion, suturing, and blood tests.

Shazalyn uses calico dolls to talk to the children and to “perform surgeries” on the dolls. This play method helps children be aware of the treatments they will be going through at a developmentally appropriate level. Thus, they will express themselves better when they see their dolls as an extension of themselves.

The dolls also serve as a form of emotional support in an unfamiliar environment, coupled with the child life therapists who offer a listening ear and a supportive environment through play.

Social stories

Shazalyn believes that many hospital-related fears and anxieties stem from a lack of understanding. For instance, misconceptions may surface when children consume media content or even when they overhear snippets of the conversations between the doctors, nurses and their parents. Children are, after all, highly observant of their surroundings.

She remembered a time when a child overheard a conversation between a doctor and a nurse about the use of contrast dye, usually injected into the veins, to be more visible in the scans.

“The only thing that the child could make sense of was the word “die” instead of “dye.” We know they mean two different things, right? But children will not think of that. That’s when misconceptions occur. I needed to let them know what they are going through to avoid possible misunderstandings.”

Here is where Social Stories come in handy.

“Let’s say the child needs to go for an operation. I will read a story featuring another child who is preparing for one. While going through the pages and asking questions along the way, the child will know what to expect at different stages in time—before, during and after the operation.”

Through these interactions, she can gain valuable insights into what each child is thinking, why they feel that way and how their thoughts may lead to them exhibiting certain behaviours.

Reducing trauma and stigma

Over the years, there has been a focus on individualised care, which recognises and validates a child’s subjective experiences, and provides specialised support and treatment they require.

Shazalyn recounted a time when a child needed to be held firmly while undergoing a particular medical procedure. Being physically restricted with little or no movement can be a very frightening experience for the child. If the experiences and feelings are left ignored or unexplained to the children, there is the possibility of lingering effects of trauma or nightmares after their hospitalisation.

By providing the necessary support and resources, child life therapists help children understand why they have to undergo those surgical procedures.

Most importantly, children need to know that doctors and nurses are not there to punish them—they are there to help them recover as quickly as possible.

“There are some people who think that we are there just to play with the children, but that is not true,” Shazalyn explained. “We use play as a tool to educate the children, to allay their fears and anxieties, and help them cope better with their experiences in the hospital.”

She added that there is little emphasis placed on the psychosocial wellbeing of children in Asian countries compared to Australia and the UK, possibly due to the stigma of seeking psychological help. Consequently, some parents or even medical professionals may think that it is unnecessary for additional support in the hospital.

“What is the biggest lesson you’ve learned from interacting with children at work?” I asked.

“Never assume the child knows nothing,” Shazalyn laughed.

“What do you mean?”

“Some parents may not want to say anything to their children about their treatment and surgery, but not saying anything to them can also backfire. The children collect these bits and pieces of information as they observe people around them.”

“So that means their imagination might run wild, and a lot of misconceptions and false information might be planted in their minds if they were not clarified.”

Sticker treasure hunts

Shazalyn firmly believes in a holistic approach when it comes to caring for children in the hospital—right at the beginning, even before the child receives treatment. “We want to get the child, their family members, including their siblings involved as much as possible in child life therapy.”

Besides working with the children’s family members, Shazalyn also works closely with psychologists, art therapists, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists, depending on the children’s individual needs.

When some children are referred to her for refusing to walk after the surgery due to anticipatory pain—the fear of feeling pain—the goal of the therapy will then be to encourage them to overcome the psychological barrier by taking the first step.

“When that happens, I will organise a sticker treasure hunt in the ward to motivate them to move, overcome their fear of feeling pain, and to start walking again. They are usually very excited when they see their favourite themed stickers pasted around the ward!”

It brought back memories of her seeing them in action. “Such an activity would also make them momentarily forget about the pain. Even if the pain were to return, they would be more confident since they have already taken that first step.”

In these cases, the physiotherapists will also be present to support the children when they begin walking after their surgery. She believes that collaboration between different partners will undoubtedly be helpful to ensure the provision of holistic care for the children until they recover.

The future of CLT in Singapore

Currently, many parents are unaware that child life services are offered in children’s hospitals. That is why Shazalyn is passionate about raising awareness of the importance of child life therapy.

At this juncture, there are two hospitals, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital and National University Hospital (NUH), offering child life services. Children’s Cancer Foundation (CCF) also has a team of child life therapists who specialise in supporting cancer-stricken children.

Shazalyn beamed with delight when we discussed the prospects of child life therapy in Singapore, “I think the situation has improved over the years after speaking to doctors and nurses while doing inpatient services.”

“What can we do now moving forward?” I asked.

“More advocacy still needs to be done to get parents on board as child life therapy is essential,” Shazalyn said. “I believe we are moving ahead. One, two steps ahead. That’s good and very encouraging.”