All images by Xue Qi Ow Yeong for RICE Media.

In the kampung where his mother grew up in, neighbours would freely loan—or even give— household appliances to each other, social worker Lewis Woo tells me.

When old-timers speak of this elusive ‘kampung spirit’, a camaraderie born out of shared poverty and hardships, they speak of a time when nobody locked their doors. Neighbours shared food and minded each other’s kids. If you needed help, your village was there for you.

ADVERTISEMENT

As our kampungs have slowly disappeared, though, the conversation around kampung spirit seems to have shifted around how we can rekindle it, or what we’re doing to keep it alive. There’s a sense that as we’ve gotten further removed from our kampung lifestyles, our collective kampung spirit has diluted. We’ve become individualists, ensconced in our high-rise flats, with our gates firmly shut.

But one platform is quietly helping to bring back that spirit of community, albeit with a digital twist.

KampungSpirit, an online donation platform, allows those in need to submit crowdfunding requests via a social service agency. The requests can range from something as small as a new pair of spectacles, to funds for renovation works. Donors can then chip in to help fund the requests.

Once the request is fulfilled, KampungSpirit, an Open Government Products (OGP) initiative, does the rest of the work, procuring the item and making sure it reaches the beneficiary.

The platform’s numbers are impressive. Since its launch in January 2024, it has raised over $120,000 and helped over 330 households. But behind these figures lies a deeper story—one about human connection, the need for dignity, and the ingrained discomfort many Singaporeans feel when they have to ask for help.

A New Fridge, a Fresh Start

For Sam Weng Choy, a 42-year-old food delivery rider, making ends meet is an everyday struggle.

Weng Choy has to undergo dialysis treatment for his kidneys three days a week. His kidney ailments were a result of the long hours he worked at his mechanic job in the past.

“Work too much. Overloaded,” he offers gruffly.

Now, he delivers food whenever he’s not at the dialysis clinic. Still, the most he can make in a good month is around $800 to $1,000.

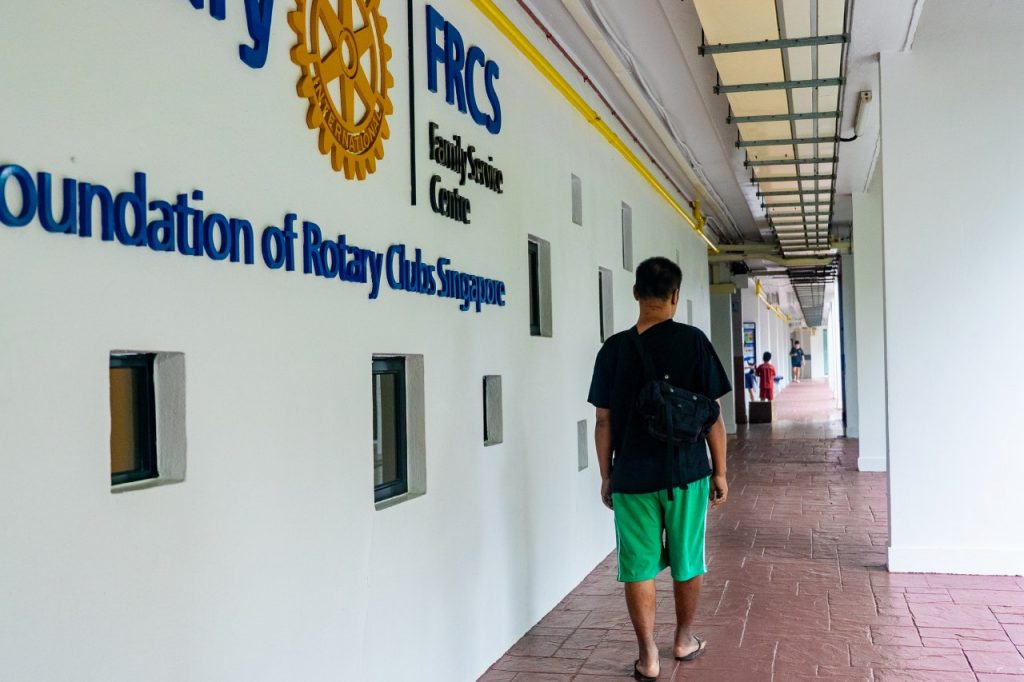

When he found himself in need of a new fridge some months back, and couldn’t afford to drop hundreds of dollars, the Foundation of Rotary Clubs Singapore Family Service Centre (FRCS FSC) in Clementi suggested KampungSpirit.

Securing a brand new fridge took a weight off his shoulders, Weng Choy says, looking pretty chuffed. He’d considered getting a second-hand fridge but asked the crowdfunding platform for a new one instead.

“I tried getting a second-hand washing machine before, but it only lasted for a year. If the fridge spoils, and I have to ask for it again, it will give [the social workers] trouble.”

ADVERTISEMENT

But the relief isn’t just about getting the appliance. It’s about the symbolic value of receiving something brand new—a luxury that those in need don’t often experience.

Donated and second-hand items are, of course, meaningful in their own way. But getting to enjoy a brand-new item is a different feeling.

Lewis, a social worker at Care Corner Family Service Centre, puts it this way: “For some people, owning a new item is like starting life afresh. A brand new fridge or washer might seem trivial to others, but for them, it’s a huge thing.”

“The psyche that we found is that a lot of times when people are going through challenges, they feel they’ve lost control over many aspects of their life. And when you lose control, that causes a lot of anxiety. So being able to choose what you want actually gives them back that sense of control.”

The Struggle of Asking for Help

Yet, despite the tangible benefits, asking for help is not easy. For Weng Choy, like many others, there’s a deep sense of discomfort around seeking aid.

“I try not to disturb people unless I really have no choice,” he says.

This tension—between independence and the vulnerability of asking for help—is why I think KampungSpirit’s model works. I’m not sure if this was the intention of the platform’s creators, but its digital nature allows people like Weng Choy to remain anonymous, giving them the space to ask for what they need without the awkwardness of face-to-face interactions.

“If I can get more help online, then I will look for it,” Weng Choy confides. “If you ask me to rely on people [in real life], I don’t prefer it.”

It’s a sentiment that also resonates with Nurul Jannah Hamzah, a single mother of two special-needs boys.

“I don’t want to trouble other people, especially my family members. So I feel like it’s better for me to approach Care Corner for help,” the 37-year-old tells me.

“They are a neutral party. They can offer ideas and assistance. Sometimes, I feel that family can be judgemental.”

In a society that prizes self-reliance, acknowledging your inadequacies and asking for assistance—especially in person—can feel like an insurmountable obstacle. As Nurul explains, “Some people are very scared to share their downfall, because society might look at them as weak.”

The Quiet Power of Crowdfunding

In Nurul’s case, the KampungSpirit has provided more than just material support. Nurul left her senior office manager job during the pandemic to care for her two special needs children; her 17-year-old has autism and mild cerebral palsy, and her 8-year-old is autistic as well.

Nurul later secured a hybrid job as a marketing director at a non-governmental organisation, but still couldn’t cope with the work demands. Since then, she has been earning enough to sustain her and her kids through content creation, but she always wanted to upskill, she says.

Even after subsidies, a digital marketing diploma offered by ASK Training would cost her $500. Besides having to cough up that amount in cash, she was also worried that devoting time to her studies would leave less time for her to work.

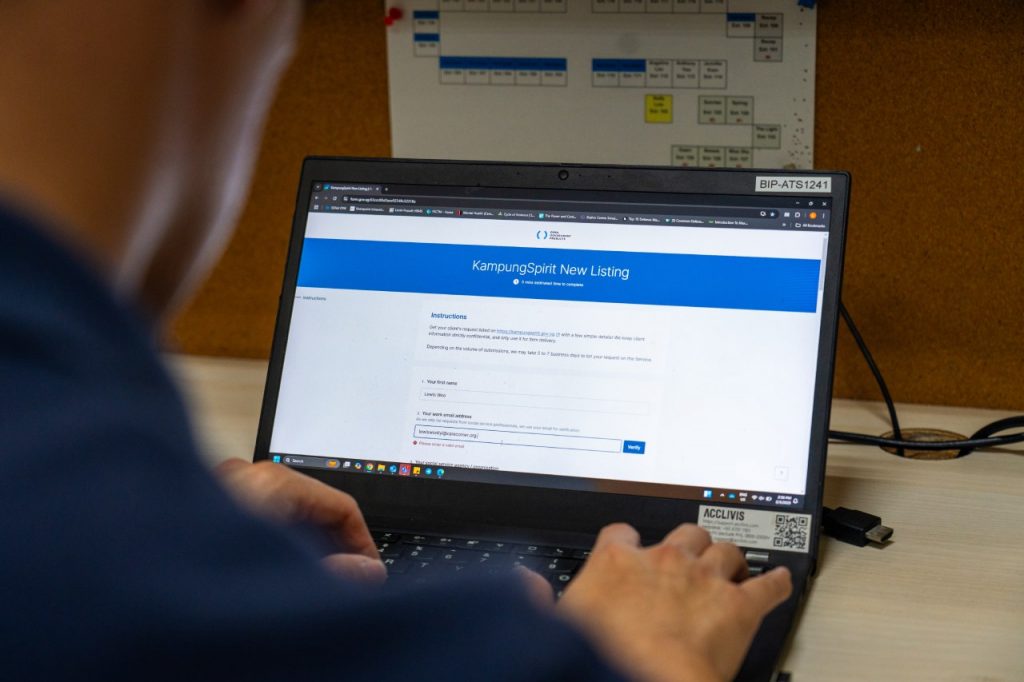

Lewis, her social worker, recalls that he was aware of KampungSpirit, but wasn’t sure if they’d accept Nurul’s request to fund a diploma.

“When I first pitched the idea to KampungSpirit to raise funds for the diploma, I went in with this ‘let’s try’ mindset. I was pleasantly surprised they actually agreed to have the listing listed.”

Nurul herself tried to keep her expectations low.

“I didn’t hope so much because I thought it was impossible,” she admits. “I didn’t think this sort of thing could be paid for by others.”

To her surprise, her funding request was met with overwhelming generosity.

“People are actually doing crowdfunding for my studies, so all the more I feel motivated. I want to work hard,” she says animatedly.

These anonymous donations lit a fire under her, and she ended up graduating the course with a distinction.

Lewis chimes in: “When she sent me the picture of her graduation, I almost cried. I was very happy for her.”

Today, Nurul is on her way to a new career, having secured several job interviews thanks to her diploma.

Ju Zheng Yang, Weng Choy’s social worker, adds that he sees great potential in KampungSpirit as a driving force for mutual aid.

“Through this kind of movement, my clients see that there are many kind people in society willing to contribute to help them. I also believe that this can also influence others. We get more people to come together to support other vulnerable families.”

Rekindling Community in an Isolated World

KampungSpirit highlights a sobering reality: it’s easier for many people to accept help from strangers on the internet than it is to ask for help from friends, family, or neighbours.

The reality is that the Singapore of today is markedly different from the one that birthed the kampung spirit myth. We have to accept that the magic of kampung spirit is impossible to recapture in its original form, simply because we’re no longer facing the same struggles of abject poverty and unemployment. We also no longer live in villages with poor infrastructure run by secret societies.

While we can’t hope to recapture the kampung spirit of the past, when neighbours relied on each other because they had to, we have something that’s different. We have communities that transcend village—and even familial—boundaries. We have social media and technology to give voices to people who need help. And we have thousands of people willing to contribute their money to improve a complete stranger’s quality of life.

Pitching in $10 for a fellow Singaporean to buy a new fridge might be a simple act. It’s also evidence that there is still kindness and selflessness out there. We didn’t leave our compassion behind in our kampungs. Mutual aid may look different now, but it still takes a (virtual) village.