Top image: Xue Qi Ow Yeong for RICE Media

Seeing the Soon Heng drink stall’s shutters drawn down at Maxwell Food Centre for the first time felt strange.

The hawker stall, run by two curt but genial brothers, was never closed. Seven days a week, before I clocked in at our office nearby and after I knocked off, Soon Heng’s lights always stayed on. But on that day in November 2023, its metal shutters were down without any sign or note offering clues about where the brothers had gone.

Weeks passed, and the Soon Heng uncles’ absence became a major water-cooler conversation topic: Was the stall still closed? Were they just taking a holiday? Had something happened to them?

Their absence was keenly felt. Over the years, their drink stall had become RICE’s favourite. Their kopi was always robust; their teh-o kosong peng was never diluted. And, crucially, their iced lemon tea always had a generous squeeze of lemon juice.

As suddenly as he disappeared, the younger brother, Ricky Tay, also known to customers by his Chinese name Jing Bao, reappeared at Soon Heng with a grey makeshift glove over his left hand.

The 51-year-old moved with a hint of unfamiliarity, keeping his covered hand gingerly at his side. His right hand, however, poured teh and kopi with practised ease, stirring in milk and sugar at the same steady pace as always.

As it turned out, many things had happened to the Soon Heng brothers. In a matter of a week, Ricky had lost his brother to lung cancer. Ricky also lost four of his fingers on his left hand in a freak sugarcane juicer accident.

It was the latest event in a series of unforeseen tragedies. Just three years prior, he’d lost another elder brother to cancer.

“I try not to think about it,” he tells me and my colleagues when we catch up with him at his home, a humble three-room HDB flat in Jalan Kukoh. This, as we would learn over the course of our conversations, is his mantra.

For years, Ricky drowned his losses in work, piling on the hours as a hawker to dull any emotional pain. But now, faced with the force of his most physical loss, he’s hit a turning point.

Ricky is realising, at long last, that there’s more to life than work.

The Daily Grind

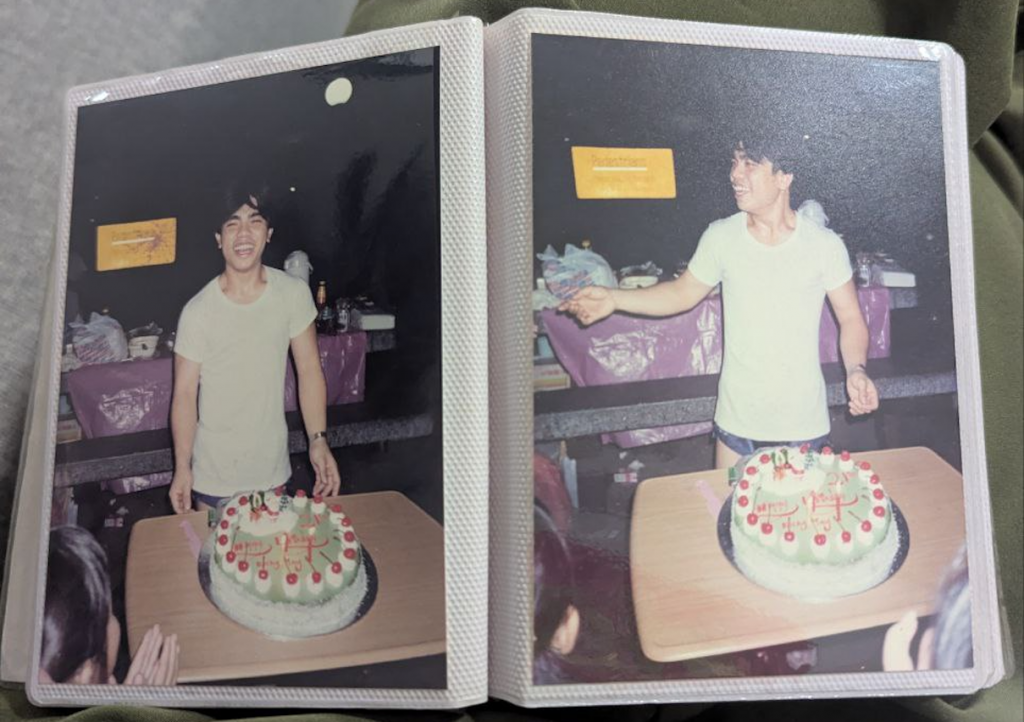

It’s a weekday afternoon, and we’re perched on Ricky’s sofa, looking through faded old photographs. Seeing him in a setting other than his Maxwell stall is a novel experience. And so is perusing the artefacts of his pre-drink stall life.

Ricky, now a portly man with a practical buzzcut, shows us photos of himself as a strapping young man. He’s handsome, with a thick head of hair, a bright grin, and running shorts that are almost too skimpy.

“Life back then was comfortable—no worries,” Ricky, the youngest of seven siblings, remarks.

Things weren’t financially comfortable. But life was simpler, he explains. Since he can remember, his family has been in the drinks business. His father sold soya milk from a pushcart in Chinatown for decades until he passed away in 1976.

Supporting a family of nine off a single pushcart’s takings would probably be impossible today, but back then, they made it work. Even if he had to go without food sometimes, Ricky speaks of a carefree childhood.

“I was always out playing and was never home,” he says, his eyes crinkling.

Gradually, though, the realities of adult life began piling up. Ricky and his three brothers took it upon themselves to keep the family business going.

Over the years, the baton passed from his father to his uncle, then to his elder brothers, and finally to him.

In the ‘90s, the humble soya milk stall moved from Chinatown—where they’d set up a permanent storefront—to Maxwell Food Centre. The Soon Heng as we know it today was born in 2000, when the family decided to pivot to become a drink stall selling the typical assortment of tea, coffee, canned drinks, beer, and sugarcane juice.

People often speak of their family’s hawker businesses with sentimentality, and I’m no exception. I expect the usual spiel about carrying on legacies and keeping their heritage alive. With how long they’ve kept the stall going, it has to mean something… right?

Ricky is refreshingly straightforward and utilitarian.

“I’ve never thought of doing anything else because the stall has been here all along,” he says matter-of-factly.

The man even laughs when we ask if he likes operating a drink stall. He laughs as if liking one’s job is a foreign concept.

“What can I do if I go out and look for a job? My education level isn’t high.”

For someone who isn’t particularly passionate about his job, though, he’s committed.

After studying till Primary 8 (still a thing in the ‘70s), he enrolled in a Vocational Institute, the predecessor to the Institute of Technical Education (ITE) of today. Upon graduation, he worked as a driver for a few years, juggling his full-time job and helping out at Soon Heng. Back then, he’d open the shop, manning it from the early morning till 9 AM before heading off to work his actual job.

It was only when Ricky’s third brother passed away in 2021 that he threw himself into Soon Heng full-time, working 16-hour days. He’d open the shop around 7 AM and stay ‘till 11 PM to close up. It was a punishing schedule that left him only around three hours of sleep on most days.

For Ricky, showing up for your family is synonymous with showing up for work.

He’s forthcoming when we ask about his family and Soon Heng—he rattles off his work schedule without any hesitation. But he stumbles when the topic turns to him and his emotions. It soon becomes clear that his brothers were the same way.

“We three brothers are close. But we never really talked about personal things,” he contemplates for a bit.

“We just discussed things like, ‘Did you order that thing?’ We didn’t really say stuff like ‘How are you?’”

Still, his siblings’ deaths hit him hard, even if he doesn’t exactly have the words to describe it.

“It’s my own brother. Who wouldn’t be sad? But there’s nothing I can do.”

A Bitter Brew

Ricky’s had a rough few years—losing multiple siblings, then his mother just weeks after our chat, and coping with the loss of most of his left hand.

After multiple surgical operations, he’s left with a fleshy stump where his fingers used to be, along with a thumb that doesn’t have full mobility.

Since the day he returned to Soon Heng, Ricky keeps it covered up under a makeshift mitten fashioned from some fabric. I’d assumed it was still healing, but he admits that he hides his stump so it “doesn’t scare customers”.

Even with the mitten on, casual customers might not notice anything odd. He’s learnt to run the drink stall with just one hand, from opening the stall’s shutters to using the crook of his elbow to hold open the fridge doors.

You never really realise how many things in life require two hands until you lose one of them. Ricky tells me that it’s the simplest things that sometimes still trip him up.

Measuring out condensed milk used to be a two-hand affair, with one hand pouring out the cloying syrup from a can and the other holding a spoon. Now, he has to pour the milk out with his remaining hand, eyeballing the amount. When he gets it wrong, he ends up with kopi that’s a little too sweet, he candidly admits.

I don’t doubt that he’ll finetune it soon enough. Already, over the last few months that he’s been back, he’s gotten visibly more comfortable with doing everything (literally) singlehandedly.

The more we talk, though, the more I realise that his method of dealing with everything is to repress the hell out of it and throw himself into work.

Over the course of our chats, a common refrain that he defaults to whenever the conversation turns to the unfortunate losses in his life is “I try not to think about it.”

Even when he speaks about the traumatic evening he lost his hand, he’s unemotional.

“Regrets? There are regrets but it’s happened already. All I can do is accept it.”

On the night of the accident in November 2023, he’d gone to open up the shop even though his friends and family had told him to take the day off. He’d already spent seven days mourning his elder brother. As soon as the wake was over, he returned to work at the drink stall, never mind that he’d barely had any rest.

“My mood was very bad. I was thinking that it was just me left at the stall. I was thinking about how I would have to endure it and continue working,” he says.

At around 11 PM that night, he’d decided to clean the sugarcane juicing machine—a task his late brother usually undertook. In his sleep-deprived state, he hadn’t realised his left hand had gotten stuck in the rollers—the same rollers that effortlessly flatten dense sugarcane stalks.

It was only when a regular customer sitting by the stall noticed and yelled at him that Ricky realised what had happened. By then, it was too late. His fingers were stuck in the pulping rollers.

What followed was hours of anguish. Paramedics arrived swiftly but couldn’t figure out how to free his hand. They ended up having to call the sugarcane juicer maintenance man.

By the time he was freed and loaded into an ambulance, it was already 4 AM. He was so exhausted that he fell asleep, he says. When he woke up some three days later, he’d already lost the fingers on his left hand.

Although Ricky recounts the incident with the calmness of someone describing how he sprained his ankle, it’s not lost on me just how scary and traumatic it must have been.

And it seems to have precipitated a fundamental shift in Ricky’s workaholic ways.

“I do blame myself. People told me to rest—even just for a few hours or once a week—but I never listened,” he says.

“Now, I feel like if you need to rest, you should rest. Don’t force it.”

I ask if he’s walking the talk and sleeping more nowadays. He laughs sheepishly, admitting that he only manages about five hours of sleep each night—a marginal improvement over his usual three hours.

The 16-hour workdays are a thing of the past. His cousin’s kids and his sisters sometimes help out at the stall, allowing him to leave earlier these days. But even when he’s got more downtime, he finds it hard to fall asleep at night. Thoughts of his late brothers keep him up sometimes, he confesses.

His elder sister, Sandy, tells us that the past few years have been hard on the family. She’s emotional when she speaks of her younger brother’s freak accident—even more so than Ricky himself.

“My heart really hurts that something like this happened. I’ve been taking care of him since young. When I got married, he was the little boy helping to open the car door.”

She tells us that she’s been urging Ricky to rest more for ages. But it’s only after he lost his fingers that he finally listened.

The pain is evident in her voice when she tells us how she’s seen her brothers put on a brave front through their struggles: “Even when they had cancer, they never complained. I think they didn’t want our parents to worry.”

I remember seeing Ricky’s eldest brother at the shop regularly before his passing. Who would have known he was suffering in silence all along?

To the Last Drop

I can’t lie; the steadfast dedication to showing up to work every single day—no weekends, off days, no sick days, no mental health days—is not something I can relate to. I’m not sure if I could cope with working seven days a week, let alone 16-hour days. I can also see why the older generation might label people like me strawberries.

The truth is, being able to take time off for mental health and self-care is a privilege. For people in Ricky’s financial situation, with minimal savings to fall back on, work-life balance lies low on the list of priorities.

An office worker gets paid bereavement leave. But a hawker who closes his stall to mourn a family member’s passing misses out on the day’s takings and has less to feed his family at the end of the month.

Ricky tells us that for many hawkers, taking a day off doesn’t feel like rest because you still have to prep your ingredients for the next day. Yet, taking even two days off feels like too long of a break.

And these days, the dollars don’t stretch as far. Ricky barely makes around $3,000 each month. With two kids—a 14-year-old daughter and an 8-year-old son—it’s just enough to get by, he says.

Retirement is a distant dream.

“Retirement? In this country? It’s very hard for people like us,” he says. Ricky’s referring to people living paycheck to paycheck. Or, as he puts it succinctly in Mandarin: shou ting kou ting. “Hands stop [moving], mouth stops [eating]”.

Still, Sandy says she’s been trying to get him to stay true to his word and rest more.

“There’s a long road ahead of us,” she offers. “No matter how much or how little you earn, you must rest.”

When Ricky disappears from Soon Heng again for a few days, I immediately assume the worst. Fortunately, it’s just Ricky taking some self-care baby steps. I hear from the other stallholders in Maxwell Food Centre that he’s gone to Bangkok on a volunteering trip with a friend—an uncle selling fruit juice a few stalls down from Soon Heng.

He’s all smiles when I ask him about it after he returned. Even though the pair probably spent more time volunteering with orphaned children than sightseeing, it was still a fun time, he says.

“I even got those Labubu toys for my kids,” he says, nodding toward the trendy plush toys displayed proudly on their table beside a stack of school books.

He’s never really had big dreams for himself, and he says he plans to run Soon Heng until he dies. But I wonder if he has any dreams for his kids.

He lights up as he tells me he’ll support them in anything they want to do. He laughs about how his younger son has expressed interest in being everything from a bus driver to a soldier.

One thing is for sure, though: he doesn’t want them to follow in his footsteps. The work is simply too backbreaking, he says. While they figure out their aspirations, he’ll be behind them in the meantime, providing as much as he can.

“I don’t know what it means to be a good dad. I can’t educate them. But I can make sure they grow up healthily.”

Stronger Than Gao

There are two types of people: Those who yearn for free time and those who feel lost when they have it.

I’ve always been firmly in the first camp, so speaking with Ricky offered me an unexpected glimpse into the latter’s lives.

For many like him, it almost feels safer to keep working; there’s a comfort in the routine, in the way it keeps the harder questions at bay. When the work stops, what fills the silence? How do you sit with grief that’s been building up? What does fatherhood mean when it’s about more than putting food on the table?

For Ricky, whose entire life has been a relentless rhythm of hard work, shifting gears to simply be feels like foreign territory. Time off is less a luxury and more an unsettling space, revealing everything routine has managed to obscure.

In his generation, love has been woven through quiet acts of service: bringing home the bread, maintaining a brave front so others don’t worry, lending a hand at a family business, or noticing when the pantry needs restocking. Love is often silent and practical, measured by what one does rather than says.

But bit by bit, Ricky is learning that love can also mean caring for yourself. Not for how it helps others but for its personal necessity.

In a way, he’s now discovering a new language of care—one where rest is not a weakness, where kindness toward oneself isn’t a luxury.

It’s still poignant to see Ricky running the stall these days without his eldest brother. And I’m sure it’s harder for him, having to spend all that time at work in a space where everything reminds him of his deceased family members.

But he’s finding strength in the people who are still around.

“Truthfully, it’s also because of people like you guys,” he grins.

“The regular customers. The people who will ask how I am.”