Top Image: Marisse Caine/RICE file photo

How many times is too many times to bid for a Build-to-Order (BTO) flat in Singapore? Twice? Three times? Perhaps, the fourth time’s the charm.

For couple Jason Li, 30 and wife, Berenice Phang, 29, it seems like even after a staggering thirteenth time bidding for a BTO flat, a home they can call their own continues to evade them.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Five years out of our 10-year relationship has been spent trying to get an HDB unit if you want to put it that way,” laughs Berenice dryly. She and Jason sit behind my monitor screen, a week fresh from moving into their resale unit.

From the latest SERS debacle, changes in the HDB Loan-to-Value percentage, and the latest cooling measures to curb the sale of HDB units to those who own private property, it’s clear that Jason and Berenice are plunging head-first into the minefield that is the Singapore’s current housing market.

Here, nobody is safe. Especially those who dare try their luck for a BTO.

When it comes to balloting for a BTO unit, recent trends of BTOs units being grossly oversubscribed (sometimes 20 times over) have made the process of even getting a coveted queue number nearly impossible.

It’s a common narrative that is not about to see a satisfying denouement anytime soon, even after housing cooling measures were introduced.

If it’s not already clear, Singapore’s housing system is in crisis.

The (Bad) Luck of the Draw

“We know getting a BTO would be hard, but we didn’t think it would happen to us,” laments Redzuan, 30s, an Integrated Communications Consultant.

Redzuan tried six times to secure a BTO—a healthy mix of BTO units, Sale of Balance flats (SBF), and Open Booking exercises. All to no avail.

“There were a couple of times when I didn’t get a queue number at all because the BTO project was just so massively oversubscribed.”

ADVERTISEMENT

To give you an idea of the sheer number of people vying for a BTO flat, we only need to look at one of the latest BTO exercises in August 2022. 4,513 people had their eyes on the 398 four-room flats located in Ang Mo Kio’s Central Weave housing project.

That translates to more than 11 applicants vying for each unit.

Elsewhere, at the ever-popular Tampines Sun Plaza Spring project, the four-room flats were oversubscribed by around 20 times, with 3,094 applicants jostling for 150 units.

The larger five-room flats were also a hot favourite, with 2,813 applicants applying for 117 five-room flats—an oversubscription rate of 24 times.

“When I did get a number, it was like twice or thrice the available units,” Redzuan sighs. “I’m at a point where, if I’m being frank, it’s probably going to be easier to win the lottery than to get a BTO.”

HDB: We Don’t Talk About Mature Estates

In response to queries by RICE, HDB states many first-time flat buyers (labelled as FT families) would typically get their ballot number within the first three tries.

“Almost 90 percent of FT families who apply for BTO flats in non-mature estates have a chance to book a flat within two tries,” HDB explains. “Virtually all have a chance to book a flat within their first three tries.”

When probed about the same uptake figures for mature estates, HDB responded to RICE through a phone call, stating that they do not have those figures—the housing board wants to encourage applicants to apply for homes in non-mature estates.

Also, HDB adds that those who have been unsuccessful in two or more attempts for BTO flats in non-mature estates will be given an additional ballot chance for each subsequent application in such estates.

The Board also emphasises that applicants are encouraged to apply for a BTO flat in non-mature towns to enjoy a higher chance of securing a flat.

Mature = Non-Mature

Given HDB’s reluctance to share public data on take-up rates of BTO units in mature areas, it’s safe to assume that opting for BTO projects in places like Bedok, Kallang, or Tampines is setting yourself up for failure.

ADVERTISEMENT

HDB posits that opting for a BTO in non-mature estates such as Bukit Batok, Jurong East, Jurong West, Punggol, Sengkang, Tengah, Woodlands, (and Yishun) might be a better way to secure a BTO.

Not that it makes much of a difference since those projects are often oversubscribed anyway.

Jason and Berenice know this, which was why the couple also applied for units at non-mature estates, such as Bukit Panjang and Sengkang, on top of pining hope for a queue number at BTO projects in mature estates.

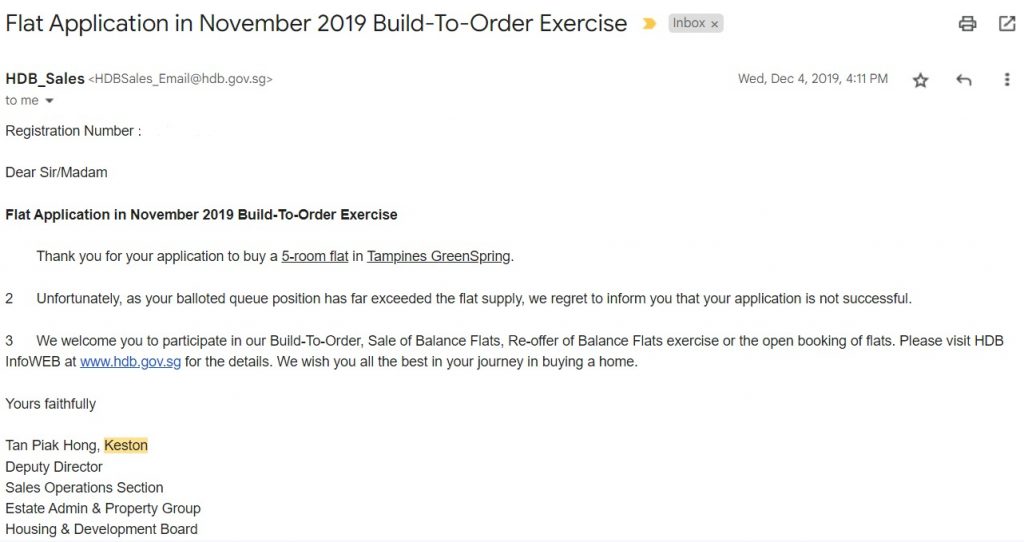

Still, their starry-eyed dreams of bringing those aesthetically pleasing kitchen ideas from their Pinterest board were quickly dashed when Jason and Berenice received another email from HDB. It was their fourth email yet—and counting—informing them that they had failed to secure a queue number.

“Whenever we receive the email notification, we pray for a while before we open the message. But the answer is the same all the time.”

“I think of those 13 times, only once did we manage to get a queue number. Even that was oversubscribed.”

Still, that’s not to say people should stop trying to get homes in these areas. After all, some have legitimate reasons for insisting on living in such mature estates.

For instance, the location might be ideal as it is close to the couple’s respective parents, so caring for future children is much easier.

BTOs: A Homeowner For Just S$10

Despite the climbing prices of BTOs and news of million-dollar resale flats, persistence and optimism is common among prospective homeowners RICE spoke to.

“The draw for me is that not only are BTOs government-subsidised flats, but they are also brand new,” Annabel Lim, who is in her 30s, shares. She tried to secure a BTO flat eight times.

“You get a brand new flat, which you can furnish from scratch. You don’t need to hack stuff away, saving heaps on renovation costs,” she says.

More than that, a BTO flat is, dare I say it, affordable. The real allure of BTO for young newlyweds fresh in the workforce is just how inexpensive a BTO is.

ADVERTISEMENT

A four-room BTOs in non-mature estates range from a reasonable S$253,000 to S$381,000, while in mature estates, they range from S$311,000 to S$617,000.

Throw in first-timer CPF Housing Grants and the Enhanced CPF Housing Grant, BTOs make for an extremely viable option for first-time buyers. Given the three or four years it usually takes to build the flat (longer during Covid), you would have time to save up a small nest egg to get a head-start on paying off renovation costs.

BTOs Weren’t Always Like This

Even as it feels the BTOs have become the bane of every prospective homeowner’s existence, BTOs are a relatively new housing system. This new-ish government initiative has only been around since 2001 with mixed results initially.

Between the years 2001 to 2003, around 150,000 government-built houses were left empty. This was before the advent of BTO flats.

Then, buyers would register under the old Registration for Flats System, where applicants would book their flats based on a general neighbourhood in Singapore.

They would know the exact spot of their estate only when they are invited to select their flats. Under this system, some buyers would inevitably be unhappy with the final location of their flat.

Under the current BTO system, potential buyers apply to the ballot for a chance to select a flat in an exact location. If the stars align and applicants are successful, you can book a home in the preferred location and choose the type of flat you want.

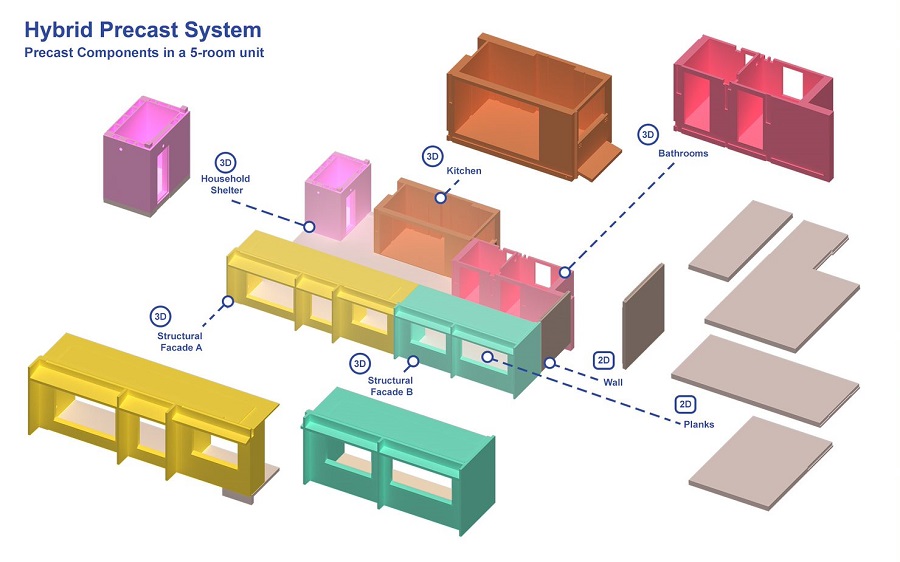

A downpayment is secured to ensure buyers are committed. HDB would then assesses the demand for each BTO project and starts construction only if demand exceeds 70 per cent.

Although it is very rare that BTO projects were ever cancelled, it has only happened five times due to a lack of demand. In fact, three of five projects were successfully relaunched.

More Than Just a House

“When you have your own place, you make the rules,” Annabel shares when I ask what buying a home means for her.

ADVERTISEMENT

“You get to decide whether or not you want the cabinets to be built-in or if you would like to leave the Christmas lights up till January,” she asserts.

While exercising your new-found independence is liberating, for Redzuan, having a place to call home allows him to deepen his relationship with his wife. While Redzuan likes living at his parent’s place, staying with them is not how he envisions his next phase in life.

“As a newlywed couple, you want your own space,” he explains. “When you live together, you can start learning new things about each other, and that cannot happen while you’re living with someone else. We need to get our own space space to move on to the next step of our marriage.”

Just like many couples who crave a space they can call their own, Redzuan decided to go down the road of clinching a BTO. And like many other couples too, disappointing results abound.

Where Have All the Flats Gone?

So, where are all the flats? With such high rates of oversubscription, it’s evident that there are just not enough BTO projects and houses to meet demand.

To this inquiry from RICE, HDB responded that they have been ramping up the supply of BTO flats and will launch up to 23,000 flats annually in 2022 and 2023.

According to HDB, this is a significant increase of 35 percent from the 17,000 flats launched in 2021.

Moreover, HDB mentions that “in terms of the supply of non-mature estate flats, which are generally more affordable, we expect to launch a total of about 12,800 flats in non-mature estates in 2022, which is about 3,550 (or 38 percent) more than in 2021.”

Officially, there is a concerted effort to ensure first-timers get to book a flat. Still, the reality on the ground seems to suggest otherwise.

Annabel, who failed eight times to get her BTO, eventually settled for an Executive Condominium in Sengkang. She seconds the notion that applicants may need to cast a wider net when searching for houses.

“The advice I’d like to give is don’t be so fixated on the location. Now, Tengah might not seem too enticing, but ten, twenty years down the road, perhaps the estate would offer a much better value compared to Bishan or Ang Mo Kio,” she says.

“Don’t be so fixated on the short term. Consider the location’s long-term developments and maybe read the URA plan.”

ADVERTISEMENT

To further meet the robust housing demand from first-time applicants for BTO flats, HDB “has increased the BTO allocation quota for first-timer families for 3-room and 4-room flats in non-mature estates from the Aug 2022 BTO exercise.”

While we can appreciate the efforts put in by HDB, a glance at the application rates for the non-mature estates tell us that the competition for those units is just as cut-throat and intense.

Take northern BTO project Woodlands South Plains, for instance. Most of us can agree that it is a tad far from most things, like the Central Business District or Orchard road (but not the Zoo).

There, the application rate for a 4-room BTO was 3,131 to 268 units—a whopping 11.7 people clamouring for a slice of Woodlands living. At this point, getting a BTO is not merely a function of luck; it is an outright miracle.

The Emotional Toll of BTOs

While getting a house is entirely transactional, it can take a mental and emotional toll to be constantly snubbed by an impartial and unfeeling balloting system.

“I’m a person who prioritises family. The fact that I couldn’t get a house so many times and couldn’t provide as the ‘man of the house’ was very frustrating,” recounts Jason. “I was full of anguish. Whenever I don’t get it, I’ll ask, what do I do?”

Berenice talks about their initial happiness and enthusiasm that, 13 BTO applications later, quickly devolved into despair and exasperation.

“After our first BTO application at Bidadari, the excitement quickly melted away. The fact we couldn’t get any queue number delayed our plans to start a family as well,” says Berenice.

“It affected us because we wanted to get married. We could have gotten married earlier if we were to get a queue number and a house ready.”

“My emotions went from excited to hopeful, then to sad, excited, annoyed, angry and finally resigned,” Redzuan relates. “My wife and I just tapped on each other and managed our own emotions. We tried not to be too sad, but we couldn’t help it.”

“Now, whenever I hear the word BTO, I cringe. It just brings back painful memories.”

ADVERTISEMENT

“We know that it is difficult,” reasons Berenice. “We also know that the BTO ballot is random. But we still went down to HDB to understand how the system works. We took our applications and showed HDB: ‘This is the number of times we tried to apply and still didn’t get anything’. We just wanted to understand the rationale behind their balloting.”

The couple found out that there is no magic or ‘secret way’ to get a ballot for a BTO unit. And if any articles purport otherwise, take their pointers with a massive dose of salt.

“There’s no such thing as bias or anything to get a queue number. There wasn’t any help that we could get from HDB, essentially. So, it was quite frustrating at that point,” says Berenice.

They then tried speaking to their respective MPs, but that was a bust too. The couple was nearing their wit’s end—even after trying all possible avenues like SBF and Open Booking to obtain that precious queue number.

To wit, Jason and Berenice’s visit to HDB was a non-starter, the ballot system is random, and no one, not even their MP, could help them get a forever home.

Giving up and Giving in

After relentlessly trying for something and failing, there is a point in time that you call the time of death and tap out.

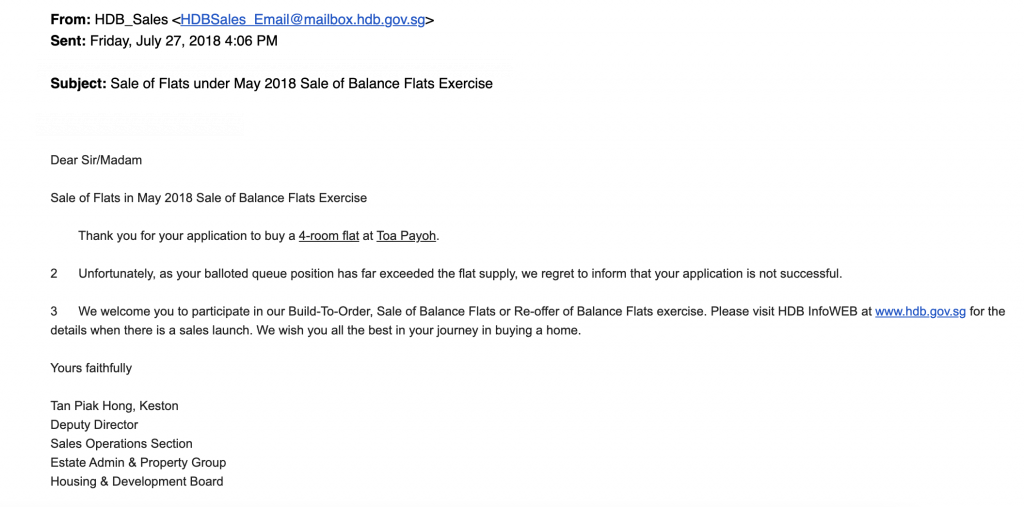

Redzuan gave up after six tries. Like most first-time buyers, Redzuan was a dog with a bone and kept trying all possible methods to secure a house.

He recalls one time when he had set up three laptops to increase his chances during an Open Booking exercise, but the slots were filled within a mere four minutes when the portal opened.

“It is a very tedious process, and it was tiring for both my wife and me,” says Redzuan, “because we tried all three routes—BTO, Sale of Balance and Open Booking—and all three have different processes.”

After the sixth rejection for an Open Booking, Redzuan gave up and started looking for a resale flat. That was another monster altogether, as Covid-19 was in full swing, and heated demand was driving up resale prices.

Their luck changed for the better when they chanced upon a listing on PropertyGuru for a one-bedder Executive Condo, which they eventually bought.

For Jason and Berenice, after a non-refundable S$120 spent on registration fees, the 13th rejection for an Open Booking was the last straw.

ADVERTISEMENT

“When we failed the 12th time for a BTO project in Bidadari, we decided to throw in the last S$10, just to see if we could beat the odds, but it was still the same results,” says Jason shaking his head.

That final nail in the real estate coffin reaffirmed Jason and Berenice’s decision to purchase a resale flat.

After being thoroughly scared by the system through the years, Jason and Berenice were in a better place financially to opt for a resale and did precisely that. Annabel did the same thing as Redzuan—she is now looking to move into a private condominium.

Still, the ordeal of trying to get a roof over her head left her with more questions than answers. “I’m worried also for the next generation, like my younger colleagues and my kids. Will they be able to afford a house in the future?” she asks.

“Would there even be a $700k HDB flat for them in the future? Or will it just be in the millions? Can they even dream of upgrading?”