Top image: RUMI THE POET’S CUP

All other Images: Hykel Quek/Rice Media

A black sedan turns into Haji Lane, stuttering its way down the road not because it needs to but because it can. Pedestrians closest to the car, alarmed by its sudden presence, cautiously move to the roadside. A sheet of A4 paper plastered along the car’s windshield reads, “This is why they need to close Haji Lane to vehicles.”

When someone turns into Haji Lane, it’s easy to forget that the road holds the title of “Singapore’s Narrowest Street“—its larger-than-life character does that to people. It’s perhaps why walking along Haji Lane on a Sunday evening—or any evening for that matter—is not the easiest thing to do.

ADVERTISEMENT

Besides navigating the crowd, there’s an off-chance that a vehicle could turn into Haji Lane at any moment, desperate to get to the street on the other side. It’s a coveted shortcut only for the brave motorist—a tight, four-metre tarmac overrun with makeshift chairs, tables, and the occasional clothes rack absent-mindedly left by a frazzled shop owner.

It didn’t use to be like this. Since 2013, Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority has created weekend car-free zones by temporarily closing down selected roads.

However, as part of pandemic safety measures, road closures were suspended. Still, despite relaxing pandemic measures, these closures continue to be put on hold.

Haji Lane is one such road that has continued to allow cars to pass through. Here, locals and tourists saunter freely down the street—barely four meters wide in some parts. Every so often, someone stops in their tracks and holds up a phone to take a picture of its many murals and street art—it’s almost inevitable you’ll end up in the background of a stranger’s shot.

Crucially, without the road closures, businesses along Haji Lane are struggling.

The case of the Curious Car at Haji Lane

I peruse these thoughts as I traverse the narrow five-foot way here at Haji Lane to meet Mr Aden, Director of Rumi the Poets Cup, a cafe dedicated to shining a spotlight on the local arts scene.

In an Instagram post by Rumi a few days ago, the cafe called for people to come together to petition to bring road closures back to Haji Lane—the soul of Singapore’s historic Kampong Glam.

“I also saw the car that drove through here just now,” Aden informs me. “Someone must have taken it upon themself to prove that no one benefits from keeping the road open on weekends.”

Aden’s love for the history and culture of Haji Lane is evident. It only made sense that the cafe he started opened on the street where he spent most of his formative teenage years.

He vividly recalls the “hipster movement” that was once associated with the street and rattles off the names of shisha cafes that occupied the same shophouses we were looking at.

“We lost the street’s character here because businesses were shutting down. Haji Lane is not about the lane. It’s about the people. It’s about the businesses here—that is the character of Haji Lane,” Mr Aden alludes to the sense of community along this road.

Aden recounted a recent incident when vendors along the street helped each other clear their belongings off to make way for an emergency vehicle. “Everyone’s clearing everyone’s stuff. This is the kampung spirit we have in Haji Lane and should hold value,” he says.

ADVERTISEMENT

Aden speaks persuasively and with charisma. It’s no wonder that his brainchild is now spearheading the voice of Haji Lane, demanding for the road closures to return.

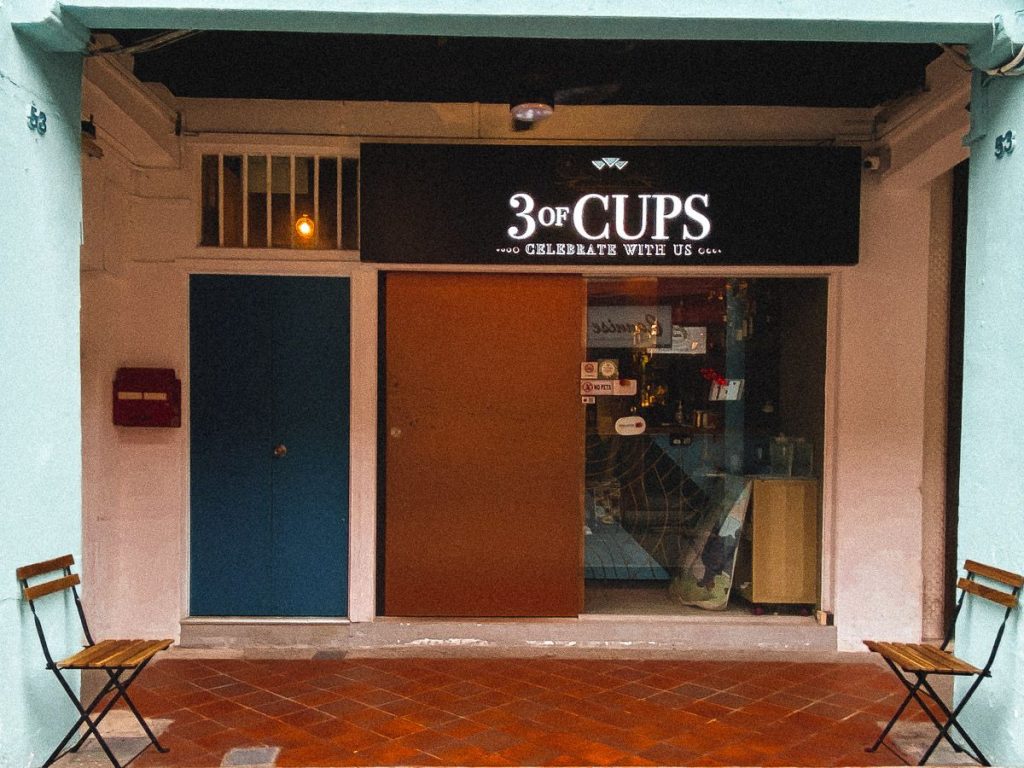

Other establishments, which are part of that unified voice to bring back the road closure, raised similar themes of the kampung spirit. Mr Ashin, a manager of tarot-inspired bar 3 of Cups, speaks on how Haji Lane’s businesses contribute to the larger street culture.

“For the community here, we support each other. For example, What the Pug relies on my customers and Rumi’s customers,” Ashin replies, “Haji Lane has a sort of road flow. The crowd flows from one part of Haji Lane to another. For example, my customers will go over to What The Pug to buy macaroons after they’re done eating and drinking here.”

Indeed, because one can find so many things to do in such a narrow street, the road has made such a name for itself both locally and internationally.

The relationship among business owners along the street has grown organically from a purely commercial standpoint to one of interdependence and community.

And it shows. During the interview, several employees and shop owners from the different establishments walked along the street, coming out of their shop units to chat.

Aden himself pauses the interview to greet some of the other shop owners and employees— another instance of that elusive kampung spirit. In fact, Haji Lane’s vendors even celebrate national holidays together.

“We have everyone here. It doesn’t mean we cannot be unified because we are competing. During Hari Raya, we set up a long stretch of tables, and all the vendors come and makan with us,” Aden recalls with fondness.

Making ends meet

Unfortunately, contributing to the street culture of Haji Lane cannot pay the bills.

The bottom line presents a sobering reality for shop owners along Haji Lane—one that is starkly different from the intangibles of contributing to and maintaining street culture. Occupying one of Kampong Glam’s earliest shophouses on Haji Lane does come with its own set of real, physical costs.

According to Aden, renting a shophouse can set you back anywhere from S$8,000 to $54,000 a month, depending on the size of the space and where it’s located along Haji Lane. While exact numbers were not disclosed, one can only imagine the rental for Rumi, a cafe that occupies an entire two-storey shophouse.

Despite its two floors, Rumi has limited interior space. When I entered the cafe for a drink, I found myself squeezed into one of Rumi’s cosy corners. Of course, small and intimate spaces were great for hanging out—not so much for business. This becomes painfully clear when customers stay for more than an hour.

At its fullest, Rumi can only accommodate 16 customers. I imagine seating plans must have been much bigger of a headache when the “one-metre” rule was enforced during the pandemic’s peak.

“If the road remains open, Rumi’s profits are projected to decrease by about 40%,” Aden estimates. “For the bars down the street, profits will probably decrease by about 50%.”

Simply put, making the road car-free creates a comfortable (and safe) environment for locals and tourists, bringing in even more foot traffic.

When the road was car-free, Rumi’s maximum capacity grew to 36 people at any point; the cafe served about 6,000 unique customers every month. It’s a far cry from the 3,600 monthly customers it’s now serving without the road closure.

To give a better perspective of the scale, what Rumi currently earns in a week without the al fresco space is what it used to bring in over three days when chairs and tables could be set up outside.

I thanked Aden for his time. Despite the difficulties, it was clear that he remains steadfast to his original vision for Rumi—a cafe dedicated to elevating the local arts scene. Car-free street or not.

The Culture of Haji Lane

I stayed a little longer at Haji Lane after the interviews. Every so often, a vehicle would turn into the narrow street. Each time, pedestrians made way for the monstrosity that is a vehicle ambling down Haji Lane, squeezing themselves into a tight frame, almost as if to blend into whatever space at the side of the tarmac.

Although cars are an infrequent occurrence, pedestrians wear the same look of disdain when they do show up. It’s almost as if the car has rudely intruded on a space meant for people and people only.

From the corner of my eye, I can see Aden, Ashin, and a few other people from the surrounding shophouses gathering and chatting at What The Pug, a new addition to Haji Lane. There is a sense of familiarity amongst themselves, made possible only through their shared experience of creating and maintaining the culture of one of the world’s coolest streets.

There’s a sense that all these efforts by the F&B owners to keep the road car-free go beyond that of a strategic business decision.

They are sticking their necks out for each other to preserve the community that they chanced upon on Singapore’s narrowest street. In many ways, keeping each other afloat means conserving the sense of community a bit longer.

“Of course, profits are important for a business, but we want to do much more than just focus on the bottom line,” Aden explains. “We try to give back to the community by organizing activities such as chess night, poetry night, and so on. We want to be more than just a business.”