I meet 38-year old Ahmad Salik for the first time in Pizza Hut at Bedok Mall. It’s lunchtime and we’re surrounded mostly by Malay diners—a fact I become hyper aware of as I spend about a minute fumbling for a politically correct way to ask him why he thinks the Malay community in Singapore is so behind.

He plunges right in without so much as batting an eyelid.

Beginning with a more scientific explanation, Salik quotes the authors of The Bell Curve, who point out a correlation between race and intelligence. He also suggests that having to learn more complex written languages like Mandarin and Tamil could explain a certain degree of cognitive advantage in both Chinese and Indians.

In contrast, most of Singapore’s Malay students learn Bahasa Melayu, which uses the English alphabet.

“Malay used to be written in Jawi (Arabic alphabet), but ever since it was romanised, many Malay children today are not able to read the Quran anymore,” he says.

“The other thing is also that culturally, Malays have never been that competitive,” Salik adds.

“That’s why people always think that we are super relaxed or laid back. And because of our Muslim background, we also see this life as temporary—a sowing ground for the life hereafter. So we prioritise other things like family, meaningful relationships, helping the community, and so on. We want a more holistic lifestyle.”

Chuckling, he goes on to say, “Look what happened with the recent Presidential election. They did it because they knew that we Malays won’t fight back. It’s like when the British first came here, we didn’t do anything. Instead, we showed them hospitality.”

At the same time, Salik cautions against looking at any of this as a “Malay problem” just because many disadvantaged families and weaker students happen to be Malay. Instead, we should be thinking about how low-income families can have the same competitive edge as everyone else, and how education reform like getting rid of streaming and the PSLE can happen.

Over lunch, however, he reveals that he thought I was interested in interviewing him about an ‘exposé’ he published on Facebook some months ago, which has since been transferred to his blog where it is documented across 30 entries.

He shares with me over email, “I wanted to become a hero, change things and help people but often ended up being misunderstood, rejected and I finally fell into depression.”

This ‘exposé’ was meant to clear the air about certain things, and even contains several apologies for mistakes he made in the past. At the same time, it details extremely intimate revelations, such as encounters with the Internal Security Department (ISD), how his third son passed away in December of 2006, and how he fell for a female colleague while still married.

His reason: “I was getting too many praises for the work that i was doing and it made me become proud and arrogant. So I decided to show my true colours by deconstructing myself. It is like pressing the restart button to start over a new life with complete truth and honesty.”

Today, relative to the soap opera proportions of his past 20 years, Salik’s life has somewhat settled down.

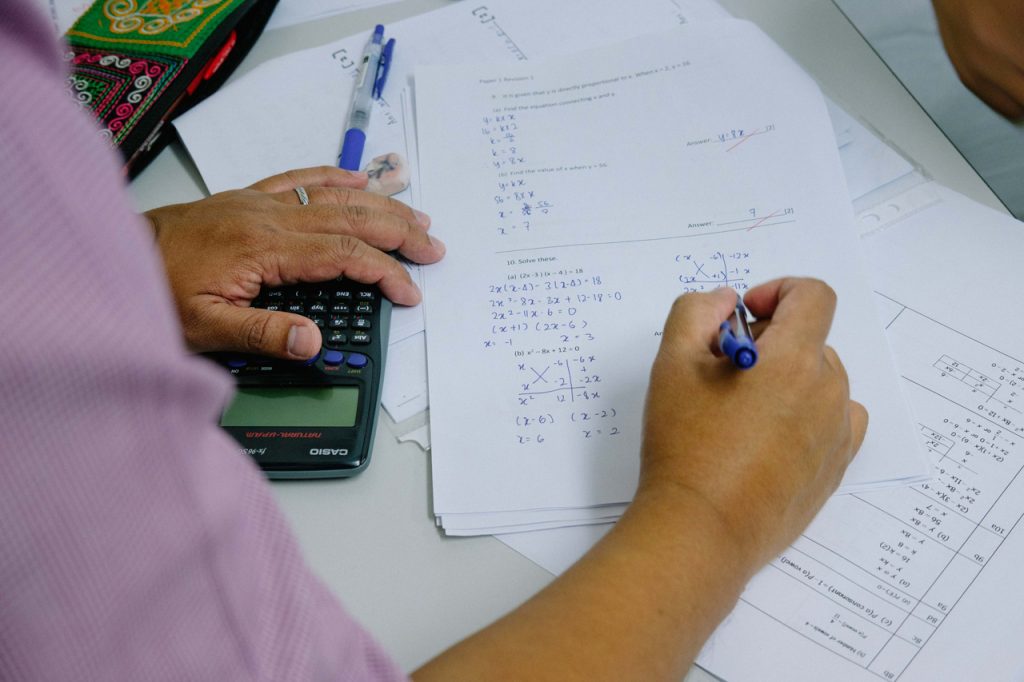

He runs a ‘study cafe’ every Saturday from 2 to 4 PM, and is free for students who can’t afford it. It’s basically a session that encourages independent learning, and he emphasises that students should only approach him for help as a last resort. After all, figuring things out on their own or working with their classmates are valuable skills in themselves.

Next year, this study cafe will expand to at least 7 new locations across Singapore. They will all be held within mosques, and Salik stresses that it’s open to everyone regardless of religion. This preserves the spirit of the original study cafe, which he started with the help of volunteer tutors and ran for 3 years, bringing together students from different schools and backgounds.

It is also line with Salik’s current long-term goal, which is to start Singapore’s first integrated school.

As a result, many students end up studying at religious universities overseas. Upon graduating, they have few career options apart from returning to teach at local Madrasahs.

“Also because Madrasahs don’t pay the best, they don’t attract the best teachers,” he adds.

On the other hand, Malay-Muslim students who don’t go to Madrasahs don’t receive a proper religious education. Accordingly, many of them end up disconnected from Islam, which goes on to affect their lives in unfavourable ways.

And so his plan is to bridge this gap, to integrate quality education with religious literacy in a single school while ensuring that neither one is privileged over the other. He also wants to focus on applied learning, and not create an environment where students study just to do well at examinations.

In the same way that Catholic or Protestant schools have morning prayers that non-Christian students can choose not to participate in, his integrated “Islamic” schools will not require non-Muslim students to participate in religious observations.

Salik also clarifies that this is a vision for all. He points out that each religion has its own belief system, and that at the core of it all is always a sense of purpose in life.

On top of this, religion is what “provides the context for learning”.

He asks, “What is the purpose of you learning this? How can this knowledge make you understand your creator, yourself and the world around you better? How are you going to make use of this knowledge to solve problems and improve lives?”

He uses the example of “1 ÷ 0 = ∞” to illustrate that with God being 1 and us being 0, we can do anything if we put our trust in God. Then drawing on how the exact value of π has never been found, he reminds the students that it’s important to remember that even mathematicians have their limitations.

The overall takeaway?

“We need to balance between religion and maths and science so that we can solve problems and contribute to society. And by learning Math and Science, we get to see many signs of God’s existence, though we must always be guided by revelation.”

After pressing for an explanation, he was told, “You won’t be able to understand it anyway.”

He confesses that he doesn’t know if it had anything to do with him being Malay, but it was an incident that has shaped a need to prove to others that one doesn’t need a degree to prove their worth or be successful.

Out of frustration, he went straight to the admissions office and withdrew from NUS.

Following this, he decided to attend a Pesantren (an Islamic boarding school) in East Java, Indonesia, to brush up on his Islamic knowledge. There, he realised that things weren’t any better.

It was a rigid and authoritarian environment, and lessons were conducted in a manner that discouraged questions. He had to dress differently, and wasn’t allowed to leave the compound even to visit his wife.

“It’s great if you want to increase your religious knowledge, not so much if you want to learn critical thinking,” he tells me.

He lasted a total of 6 months before returning to Singapore. But all this was enough to teach him what education should and should not be like.

“Why Malays are synonymous with Islam is because the religion has purified and strengthened the Malays as a race,” he says.

“That is why a Malay must always be a Muslim. Separating Islam from the Malay will only confuse or weaken them.”

He tells me that after his third son passed away, he lost his faith. At the time, he had been at a school camp when his son came down with a high fever, and so could only bring him to the doctor the next morning. By then, it was too late.

On his blog, he explains that becoming a secular Muslim also had to do with certain career decisions.

He writes:

“at first it felt quite liberating. no more halal and haram, free to do whatever you want. i gave up trying to please god. if he wants to send me to hell, so be it. but it didn’t take me long to realise that without god in my life, i would feel so terrible and lonely. life became so meaningless coz you know that even if you do good, your deeds will not be accepted.”

So when he describes Singapore’s current education system as a “body and mind without a soul”, he doesn’t just mean that students are facing immense pressure to get grades and pass exams. He also means that the system lacks meaning or purpose.

“That’s why when students graduate so many of them don’t know what to do with their lives. Or they don’t know how to apply anything they’ve learnt,” he says.

Yet I question if religion is necessarily the best or only way to achieve this.

While he seems to advocate for a “to each his own” approach to religion, I don’t get the feeling that ‘no religion’ is on the menu.

“So what about people like me?” I ask, “I’m a free-thinker, but I’m happy with where I am in life, and I don’t feel like I need religion.”

In response, he says, “But you don’t know what possibilities religion might open up to you.”

Which is true, of course. But it’s also something that can be said of every other thing I haven’t tried.

Eventually, I start thinking about how Salik’s story sounds like every parable ever written. A man loses his way, makes some very bad and immoral decisions, but eventually turns to God to put his life back together. Now, he believes that as long as you do everything for God and not for yourself, things will work out. So on and so forth.

It’s not an experience I’ve had, but it is one that I respect, and one that I know will resonate with many.

I also get that perhaps, for the Malay-Muslim community, things are a little more complicated. If Islam is indeed interwoven with Malay history and culture in a way that I would never understand, then perhaps religion could be the answer.

In the meantime, Salik has already gotten the support of several partners, and is on track to set up his company early next year to establish the first integrated school. His focus also remains on making education more holistic for all, and helping both parents and students realise that they don’t need to be a part of the Singaporean rat race if they don’t want to.

“Stereotypes are never 100% true,” Salik tells me, “But we also cannot ignore that there is now a negative perception about Malays. So sometimes it becomes learned helplessness or lack of motivation.

“And this is a problem we still need to solve.”