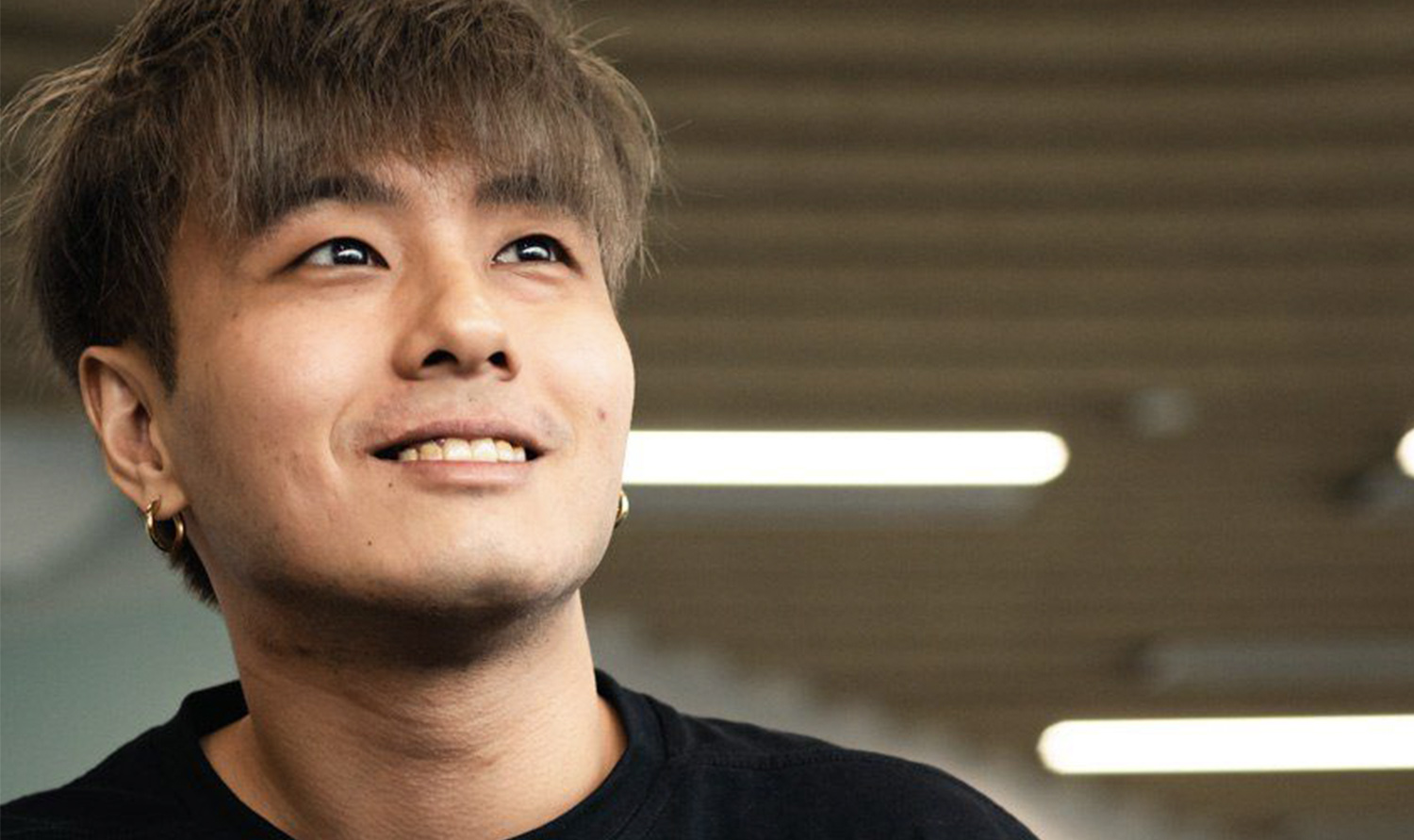

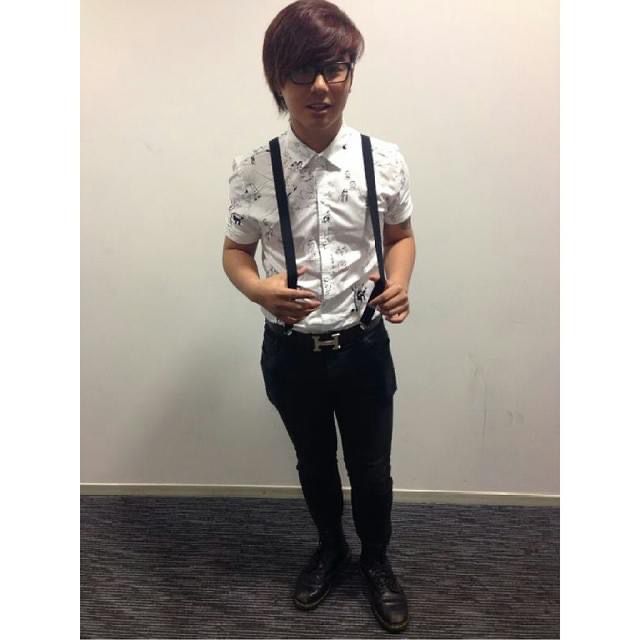

All photos by Stephanie Lee for RICE Media.

As a child, Jason Ng had the world handed to him on a plate. He and his brothers enjoyed the hallmarks of having tiger parents—stellar academic grades and enrichment classes that fill up every available date during the March school holidays. And piano lessons.

“I still enjoy playing. But mainly because girls like it when I play the piano,” the 27-year-old shares with a glint in his eye.

The cheekiness is par for the course for this PSB Academy student. The bit about stellar grades and a privileged childhood? Not something one would expect from a recently-released prisoner, incarcerated for printing counterfeit money, under the influence of drugs, after a failed business.

Stellar Beginnings

I met Jason on a Friday afternoon at the Marina Square campus of PSB Academy. It’s where he completed his Certificate and Diploma in Business Studies (E-Learning) while serving out his one-year home detention. Before that, he had spent close to three years behind bars.

It helps that the diploma is a full online course, so Jason could attend pre-recorded lectures between shifts at work and attempt online quizzes, tests, and assessments at his convenience.

“As Jason was working full-time,” Ms Toh, Jason’s probation officer, shared with me over email, “the virtual mode of classroom delivery has allowed him to balance work, class, and supervision conditions (curfew hours, urine tests, fortnightly reporting sessions) more effectively.”

More importantly, she added, the flexibility cuts down his travelling time to campus. This gives him more time to rest and, by extension, allows him to better focus on his daily activities.

In some ways, I shouldn’t be surprised that Jason could excel academically. “I was very, very good when I was a student at Unity Primary School,” he explains. How good? I asked. “One of the best,” he replies with a laugh.

But all that changed when Jason scored a PSLE T-score of 229. “I was nervous [during the exam]; I messed up,” he explains. He remembers how his form teacher shook his head in dismay when he gave Jason his results.

“It was abysmal for what I was given—all the tuition, classes, enrichment lessons. That’s when I gave up on myself.”

His mother, who had put in the effort to ensure he excelled academically, could not hide her utter disappointment. The family was supposed to go out for a hearty meal after the results were released, but all Jason could remember was his mum’s words.

“She said I didn’t deserve to eat.”

I’m surprised he recalls her exact words. “Because it mattered. That was the turning point to me becoming a ‘bad kid’.’”

That was the exact moment when Jason decided that working hard and studying hard was pointless.

“What’s the point?” he asked, staring blankly at my voice recorder on the table.

“It’s not because of what my mum said,” Jason reassures me. “But I know that no matter how much work I put in, if, in the end, I wasn’t able to deliver, so what’s the point?”

‘Turning Bad’

Jason eventually found himself in Westspring Secondary School. “I remember thinking I shouldn’t be there,” he shares.

In Secondary Two, he admitted to “turning bad”. Jason started hanging out with the neighbourhood kids—friends who, unlike him, had more freedom.

The boy, who grew up sheltered his whole life (“Up till the time I’m in primary six, I still had to have my hand held to cross the road”), demanded independence.

When he was 16, he started skipping classes and almost became the school’s first public caning case.

“For what?” I ask.

“I can’t recall.” But he did remember his mum eventually relenting and loosening her tight grip on her son.

“She accepted I was older, perhaps,” Jason offers when I pressed him to explain his mum’s change of behaviour. Still, his mum continued sending him to tuition classes. She even hired an accountant to tutor him on Principle of Account. Not that it worked—Jason simply wasn’t interested.

“School was just something I had to accept as part of life. Everyone was doing it, and I thought it was something I needed to do too.”

Eventually, Jason’s poor school behaviour caught up with him, and he was suspended from school at Secondary Four.

As a testament to his bright mind, he still managed to finish his “O” levels with 17 points.

“My prelim results were so bad; I don’t know how this happened either,” he says, laughing.

His next order of business? Polytechnic: “I didn’t think not studying was an option. I was young, and it was all I knew.”

He eventually decided to study Information Technology on the advice of his father. Predictably, it was not a field he wanted to pursue.

“I didn’t know what I wanted, so I just listened to whatever my mum and dad suggested.”

An Ice-Cold Business

Folks like Jason often struggle in the face of blind compliance. But give them independence and time to prove their worth, and one would be surprised at what they may see.

It’s what happened to Jason when he turned 17 and started selling ice cream door-to-door. At the time, he had been expelled from Ngee Ann Polytechnic–cases of delinquent behaviour against him had piled up enough.

The free time he now had allowed him to pursue his business more seriously. The side hustle soon became an enterprise when he registered the business under ACRA.

In Jason’s words, the people he recruited were ‘gangsters’. “People like them usually get their money through bad means—beating others up, helping loan sharks collect money. But I thought, why do those bad things when you can sell ice cream for me and make more?” he shares while sipping his Starbucks drink.

But it goes beyond just good business acumen. “I also didn’t want them to put themselves at risk. If money is the issue, I told them, ‘I can help you make money.’”

Still, while business was booming, he was forced to give it all up because the sellers he hired were unreliable. “Sometimes, in the middle of their sales run, they will call me and say they have to go and fight. Then my ice cream, how?”

The business held up for five years until he decided to call it quits.

Expelled

Instead of pivoting (as most Singaporeans would) to another business, Jason went back to school – to Republic Polytechnic (RP) this time around. But not because he wanted to do it.

“My mum thought I could still try to apply for RP. She was insistent that I continued my studies.” He went along with it because he didn’t want his parents to nag, Jason explains.

Jason’s stubborn insistence on going against what constitutes success while still pandering to familial expectations placed him in positions where he had to be a jack of all trades but, predictably, a master of none.

It’s what led him to be expelled from Republic Polytechnic as well. “I was often late for school because I had to manage my ice cream business. I didn’t have the time to do both.”

What led to his dark patch in life once upon a time, one may ask?

While on holiday in Perth, Jason was informed of his expulsion from RP, and upon returning home, had a rude awakening that hit too close to home: One of his best friends, Pei Ling, had died. It was reported as Singapore’s first fatal Uber car accident.

“I rejected her invitation to eat,” he recalls matter-of-factly. “So, she decided to go prawning with her sister-in-law. If I hadn’t rejected her, she wouldn’t have been in that car. She wouldn’t have died.”

Then, his grandfather passed away. Coupled with his failing ice cream business, Jason turned to recreational drug use to escape from the harsh realities of life.

In one month, he lost 30kg. But even then, his parents didn’t suspect anything.

His substance abuse, coupled with overwhelming grief, made it so that he couldn’t think or act straight. “At one point, I remembered my mum telling me as a kid, ‘You think we so rich, ah? You think we print money, ah?’”

It led him to print S$150 worth of money using his printer at home. “I even dipped the paper into coffee and microwaved it to make it crispy. Then, I put it in my wallet and forgot all about it.”

A Foodpanda cash payment order using those fake notes (“I wasn’t even using the fake notes intentionally”) led to him being visited by five police officers one afternoon.

“It was a Burger King meal,” he recalls. “When I saw the officers at the foot of my bed, I was so confused—I couldn’t comprehend what was happening.”

Jason was 21 when he was arrested. “My family, including my extended family on my mum and dad’s side, came for all my court appearances without fail. My mum especially—she was so incredibly supportive,” he says.

The Turning Point

Seeing everyone wholeheartedly turning up by his side moved Jason. He promised himself then that he couldn’t disappoint his family anymore.

It was one of the few decisions Jason made on his own without the burden of familial or societal expectations. “I didn’t want them to go through the whole ordeal again.”

While in prison, Jason decided to continue his studies. This time, of his own volition.

“If I wanted to do a big-scale business, I needed more knowledge,” he admits.

Jason turned to the one person he knew who could help him research programs offered by private institutions: His mother.

True to form, she leapt into action when he expressed interest in studying. “I told her to send me some courses I could take while in prison. We both decided PSB Academy works because it had a full e-learning diploma course.”

Currently, Jason works several jobs—data entry, luxury goods, and referral programs for insurance agents. “Anyone that needs customers and they have a service or a product to sell, I will find customers for them and earn a referral fee,” he shares over text.

The knowledge and skills he gained through the Diploma in Business Studies (E-Learning) at PSB Academy equipped him with a comprehensive understanding of the business and commercial environment.

With applied appreciation of core business disciplines such as accounting, business statistics, economics, management, and marketing, the diploma prepared Jason for the changing economy, despite having lost touch and valuable time behind bars for three years.

Future Musings

Juggling compulsory work attachment while on home detention kept Jason on his toes. He found time between job stints—a central kitchen assistant, digital lock salesperson, interior designer—to watch pre-recorded lectures and lessons.

Ms Toh, Jason’s probation officer, sang praises when I asked how she felt Jason fared balancing home detention with the rigours of studying.

“Jason’s motivation towards upskilling has made him more knowledgeable, competent and confident about himself,” she tells me over email. “He has also shown diligence, commitment, and strive during his supervision phase and brings forth positivity in his conversations with his reporting officer.”

It helps that Jason was determined to finish his diploma.

“When I want to do something, I will do my best. It’s just the way I am.” It perfectly explains why his formal education path post-PSLE has all failed—it was a pathway not of his own accord.

Jason’s journey was once a myth—that the pathways less trodden lead to a type of conventional failure. If anything, his success is emblematic of how meritocracy has changed shape over the years. But, of course, success can be subjective.

“How would you define success?” I probe.

“Financial freedom is one thing,” he offers, “but true success is to be truly happy.”

“Are you happy?”

“No. If I were truly happy, I would not still put this much effort into everything I do.”

Jason cannot tell me definitively how far he is from his definition of success—not that it matters.

“Whatever it is, I will still try my best—I’m not the kind to give up.”

As we near the end of the interview, I wanted to know what gives Jason hope.

“My past. All the things I’ve overcome, the deaths of my friends and loved ones. Everything I’ve been through, whatever that comes in the future, I can take it because I’ve gone through so much in my past.”

Jason recalls a time when he tried to take his own life. “My parents had to talk me off the window ledge. But you see, it’s only because I’ve been through such despair; that’s why I know that whatever life throws at me in the future, I can take it.”

“I’m stronger than what I think I am now,” he concludes, assured.