Top image: Mitrey/Pixabay

All names have been changed

Covid numbers don’t exactly mean much, not when you’ve been exposed to it every single day for the past two—nearly three—years now. Compared to the days when a single-digit increase in positive cases in Singapore left everyone clutching at their pearls, news about hospitalisations and deaths no longer hangs over our heads the way it used to, especially as the country moves towards endemicity with a hint of pre-pandemic sensibilities.

By this point, the double lines on a test kit tend to be heralded as a free MC rather than an actual cause for concern.

ADVERTISEMENT

That is until the dreaded double lines show up on the test results of a literal infant.

“I thought she was going to die,” 30-year-old civil servant and young mother Kassie* fumbles for words as she recalls how her daughter tested positive for Covid-19 in November 2021. Just over a month old, the young Allie* had only just been released from the hospital not too long ago, and suddenly she was going back in.

While Allie seemed alright at the point of the swab, she started having nasal congestions that left her struggling for air later that day and had to be warded in an intensive care unit at KK’s Women and Children Hospital.

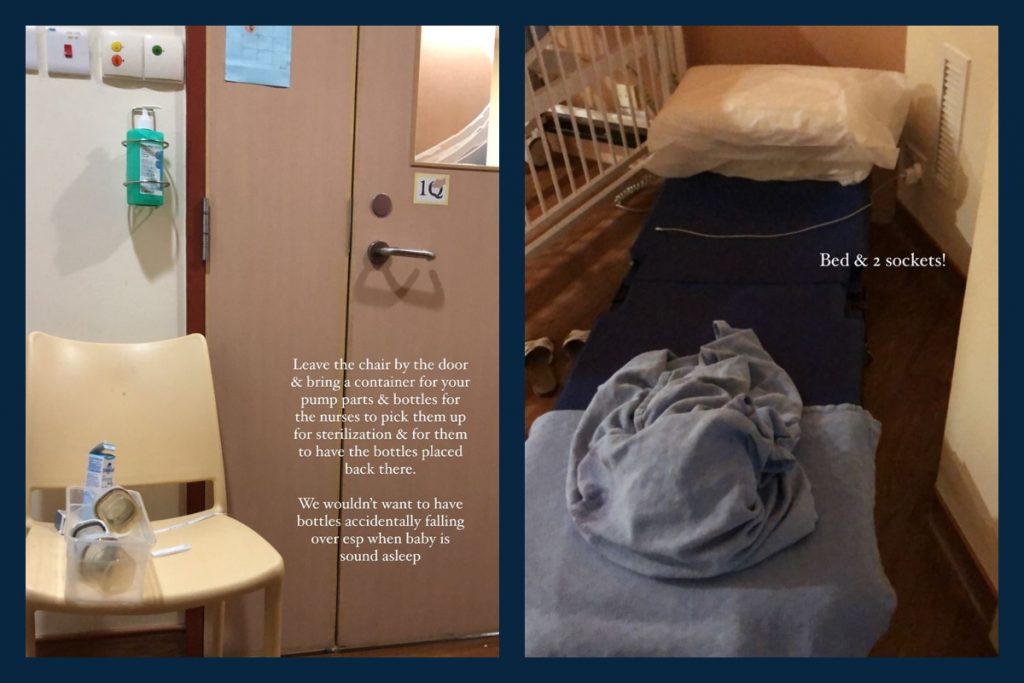

Within the four walls of the ward, Kassie only had her daughter’s sleeping figure for company. Only one caregiver was allowed into the ward so the rest of her family had to stay home. To make matters worse, her mother and husband’s cousins had all caught the virus too.

In her haste, Kassie had only managed to pack a change of clothes and roughly three days’ worth of milk powder before the ambulance came to escort the pair to the hospital.

“I didn’t know much about the virus, all I had was just this overwhelming sense of panic. I didn’t know how long I was going to be here for, or what was going to happen.”

Mummy blues meet Covid blues

Seeing Allie struggling to breathe, wriggling in pain from a PCR test and having to go through blood tests was like a dull knife twisting in Kassie’s heart. Postpartum depression wasn’t easy to begin with, but combined with her frustration over the situation and how helpless she felt, it’s as if her emotions were crushing her alive.

Between the sounds of Allie’s laboured breathing and her fluctuating adrenaline, the cacophony of children crying from the rooms down the hall seemed like a reflection of the discord within her heart.

But with her family off fighting their own battles, Kassie had to stay strong to not cause them any further worry.

“You can’t stop asking ‘how did this happen?’, but you also know it’s not like anyone wants this to happen.”

Rather than sit and wallow in her misery, Kassie began giving breast milk again in a bid to ‘do something’ for Allie. Not only did she courier her pumps from home, but she also had papaya milk delivered to the hospital every day for her consumption in order to boost her body’s production.

In a way, Kassie considers herself lucky to be in the hospital. The nurses would regularly check in on the pair and assist her with taking care of Allie. Compared to the days of her confinement, she could at least rest easy at night with an experienced pair of hands to attend to Allie’s cries.

ADVERTISEMENT

Stephanie, on the other hand, had a much rougher time handling not one, but two Covid-positive kids at once.

‘I really wanted to give up’

Five days after her mother tested positive in February, Stephanie woke up with a scratchy feeling in her throat. A day later, her six-month-old daughter started running a high fever. The next day, her two-year-old niece’s results returned positive too.

For the sake of ease, the four of them self-isolated within Stephanie’s parents’ apartment, allowing her husband, father, sister, brother in law and helpers to move around their own apartments without having to worry about cross-contamination. However, that also meant Stephanie and her mum had to handle both kids by themselves.

The biggest side effect of the omicron variant, the 37-year-old engineering trainer shares, is the heavy brain fog and overall sense of fatigue. As it is she’s already sleep-deprived and suffering from an extremely sore throat, but combined with caring for the two kids it felt as though she was stretched to her absolute limits with no room to breathe.

Her daughter could only fall asleep if she was latched, but every time she picked up her daughter, her niece would ask to be carried too. To call them a handful was an understatement — there was never one without the other. At night, Stephanie would have to keep her niece company till she fell asleep before she could put her own daughter to sleep. Even then, those prized moments of rest didn’t come easy, and the peace doesn’t last. The two youngins were light sleepers, any jostle or disturbance would cause both of them to wake up in tears, and the cycle would repeat.

As much as it was difficult on Stephanie, it was equally hard for her niece. She didn’t understand why she had to stay in the apartment or why she had to be away from her mother for so long. She took to calling Stephanie ‘mummy’ too.

It was heart-wrenching every time the young girl grabbed her grandmother or Stephanie’s hand and pulled them to the door, pointing at her shoes. She didn’t want to be locked up anymore—she wanted to see her parents again.

All this while, her daughter continued to throw tantrums from being unable to breathe right or even eat, and there wasn’t anything Stephanie nor her mum could do to make her feel better. Trapped between a rock and a hard place, all they could do was grit their teeth and force themselves to push through.

“There were quite a few points during our isolation where my mother and I really wanted to give up,” Stephanie admitted. “We thought of asking my sister to bring her girl home, but in the end everyone else, except my father, caught Covid, so we all returned to our respective homes to recover.”

Numbers mean nothing, seeing is reality

As part of the home recovery programme’s guidelines in late February, Stephanie was required to bring her daughter to KKH for a physical examination. It wasn’t until she stepped into the waiting room, surrounded by dozens of other young children and infants, did she realise just how dire the situation was.

The air filled with the sounds of children crying as the hospital staff did their best to keep up with the influx of patients. During her three-hour wait there, she even witnessed several young children on oxygen masks being wheeled in from the direction of the A&E.

“It’s horrible when you see just how many infants are affected by this,” she gripes. “All these kids just crying in front of you. You don’t see this when you see the published numbers, it’s only when you’re there do you really feel the brunt of the impact.”

During her stay at KKH, Kassie quickly realised the limited information online on what to do when an infant tests positive for covid wasn’t due to the lack of it, but purely because the volatility of the situation meant that guidelines were constantly being updated on the fly.

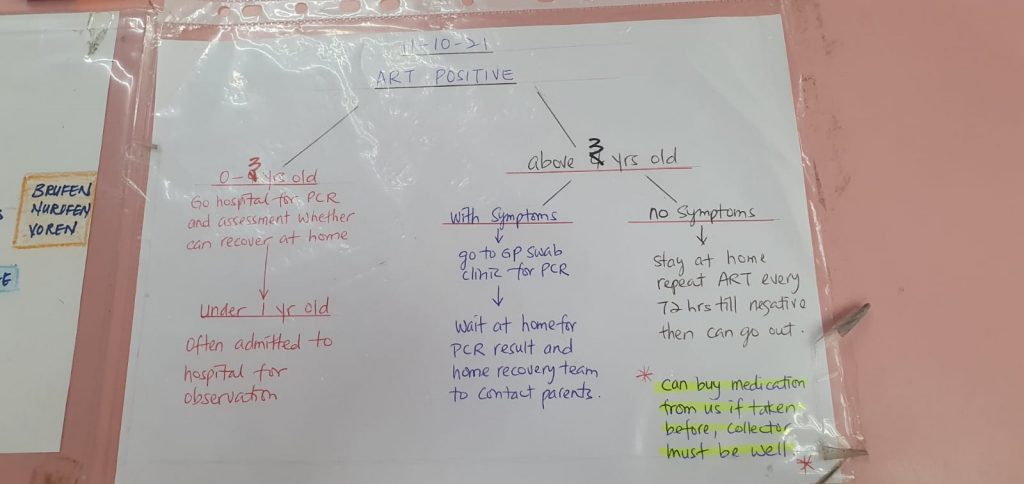

So many of the protocols had changed during the time between Allie catching the Delta variant and the Omicron variant. When Allie was warded again in March, Kassie noticed the documents pasted across the walls of the hospital were all handwritten. She reckons it’s also the reason why parents are told to wait for the officials to give them a call with the most relevant and updated instructions.

Not alone, not ever

When both mothers felt lost and helpless, social media offered them the biggest support group. Telegram groups run by paediatricians offering free telemedicine care and consultation, as well as other Telegram and Facebook groups such as SG Quarantine Order Support Group and Young Mothers of Singapore respectively, became a place where they could seek and actually get answers regardless of the time of the day.

They credit these groups for being the calm within the storm. Other mothers wrote lengthy guides listing out what they could expect—what steps to take from the moment they realised their child has fallen ill, how to sanitise the house and prevent cross-contamination, what to prepare if they had to be warded, the list goes on.

“It really takes a village to raise a child, and that goes beyond just the immediate family,” Stephanie shares. “When it’s 3 AM and you feel overwhelmed, the community is there for you.”

Following their experience with the virus, both of them have made it a point to give back to the community by detailing their ordeals at length, hoping that their post could help another parent in need. The two of them had also, almost immediately, graciously come forward as profiles for this piece.

With Covid, it pays to remain kiasu

What Kassie remains worried about though, are the underwriting issues she’d have to deal with when it comes to getting Allie insured, and the potential long-lasting effects she might face.

“I don’t know if Covid will affect her respiratory system in the future. There’s also a chance she won’t be able to get insured, or if she does, there might be an exclusion cause for anything related to her lungs or heart because of this.”

She considers herself fortunate that Allie recovered with no immediate issues. Stephanie and her family, too, had since recovered when last we spoke, though she noted there were still some lingering symptoms, especially a scratchy throat.

Long covid, as it is, has caused adults quite a fair bit of suffering. Even right now, I can hear my colleague hacking their lungs out from the next room. For young developing children, the possibility of long covid causing chronic problems like asthma, or even reverted development, aren’t completely nill.

The 7-day moving average from mid-February 2022 showed about 243 cases of children between the ages 0 to 4 per 100,000 population. Children aged 5 to 11 made up 258 cases within the same population size. It’s a small proportion, but the numbers are too substantial to turn a blind eye towards.

Sure enough, masks are no longer mandatory and social distancing measures have eased up, but the risk still remains for those too young to get vaccinated. Parents understandably feel more anxious as it gets harder and harder to protect their children. Is it, then, possible to get our lives back on track without throwing others off it?