I would never have imagined myself attending a beauty pageant. When I found myself stumbling through an understated doorway and up a staircase overlaid in drab, grey carpet, it was as though I had set foot in another world.

The club, Mana-Mana, sits on Beatty Road, a quiet lane off a main road in a neighbourhood otherwise known for its trendy brunch fare. It’s one of those places with the kind of neon blue and yellow display that’s probably visible from a passing aircraft. If you were to stroll past it at night after a family dinner, chances are that someone would nudge you to walk just that much quicker, all while averting their eyes from the strangers who linger outside, the smoke from their cigarettes rising languidly into the air.

And yet, inside, families squeeze around tables sipping beer and tearing through plates of otak-otak (grilled fish cake). An Indian lady, likely in her late 50s, said that she was there to support her daughter. At the far end of the venue stood a stage and a DJ booth. Behind it, a white banner decked out in silver glitter read, “Miss International Queen SG 2016.”

Rozy, who owns the club, gushed about how she never expected a turnout of this scale. “Especially for the Malay community it’s quite surprising,” she mused, “Because for religious reasons usually they don’t really support transgender people.”

The host of the event, Tompok, known also by her stage and performing name Cheta SG, echoed Rozy’s feelings. She also revealed that the event was more than just about bringing families and friends together. It was about creating a bridge between the older and younger members of the transgender community in Singapore.

“Even people who have had misunderstandings in the past, who haven’t spoken in many years—they all came here, and they started speaking again,” she added, as a touch of subdued emotion crackled in her voice.

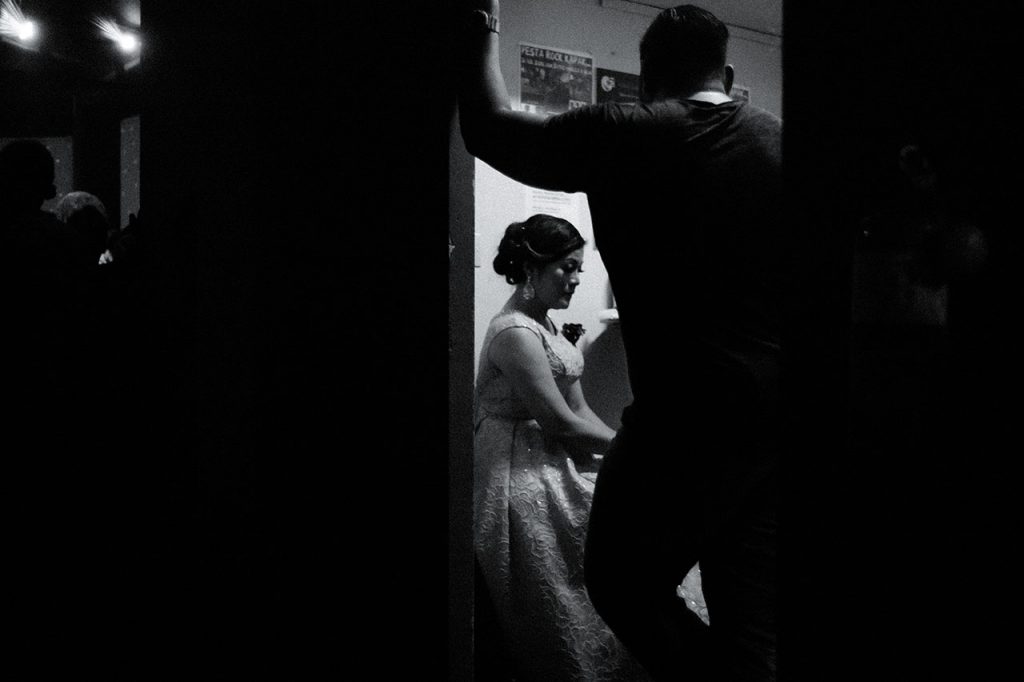

Eventually, the contestants emerged from the dressing room behind me. As they lined up in formation, cigarette smoke drifting in from the entrance swirled around them, I leaned over to ask, in a whisper, how one of them was feeling. I was immediately shushed by her stylist, as though my presence had threatened to pierce the aura of her celebrity.

As I scrutinised the heavily made-up faces, rigid with concentration, every one looked both proud and inaccessible. They seemed more goddess than mortal; more baroque sculpture than flesh and blood. Never in my life have I felt shorter or smaller than when I stood next to them in their high heels and lush, opulent costumes.

Instead, I saw women.

I saw their families and friends; raucous shrieking at every moment where a contestant was celebrated, whether for her charisma or her elegance. Awards were dispensed freely, with everything from Miss Congeniality to Miss Creativity—literally something for everyone.

They were clearly upset, and I was glad to see that. I was glad because their disappointment, for me, defined the humanity of the pageant. In that moment, the event transformed into something more than what I thought would be a biased transgender tribute. The women on stage were offered equality in being subjected to both adoration and disapproval.

They were treated like human beings, seen for what they were and were not. They were put at the mercy of objectivity and not bigotry. Their gender had nothing to do with anything. Instead, each one of them inspired both awe and annoyance, just like any other person does.

Yet this Miss International Queen pageant was no charade. The two competition categories in which the women were judged were the ‘National Costume’ and ‘Evening Gown’ segments. They were unquestionably sensual displays, but they were also tasteful, daring, and staggeringly gorgeous. There was no swim suit category.

Miss India sauntered down the catwalk with a live snake draped across her shoulders. Miss Cambodia was clothed in a green, black, and gold version of the Cambodian national garment, while a glittering, 15 inch tall tiara sat on her head. One of the ladies even wielded a brass incense burner, engulfing herself and members of the audience in smoke and a balmy fragrance as she ambled up to the stage.

What I found subtly hilarious (but also poignant) was that despite there being 19 countries represented, the contestants were all mostly local women. It was as though the pageant was more concerned with symbolic diversity, of making a statement about the universality of transgender identity, than about geography and nationality.

Outside the club, a few ladies who had come out for cigarettes and fresh air told me that the transgender community in Singapore has always existed.

“It’s just that we don’t see them or talk about them,” one said.

“Seeing all these families here today, we know it’s possible for our friends to be accepted,” another chimed in. “They are normal, just like us; everyone here today knows that. Soon, everyone else will also.”

—

Julian Wong: julian@readrice.co