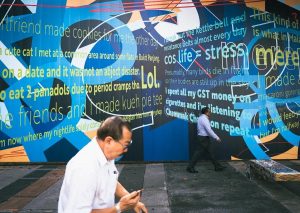

Top image: Stephanie Lee / RICE File Photo

This World Mental Health Day, we should figure out how to use our mental health days off work, because I don’t think I’m using them right.

For most people, taking a mental wellness day doesn’t come as easy as taking MC for a physical ailment. And taking MC can already be a tall order for some.

ADVERTISEMENT

Becoming comfortable with talking about our mental health struggles is a feat unto itself, and I’d like to think that I can guiltlessly acknowledge when I’ve reached my limits. It’s just that I don’t know what to do with myself when I do take a mental health day. I find myself lying around on my phone, staring into space, or straight-up napping. I end up moody, lethargic, and upset that I took the day off, and get none of the relief I expected.

What is wrong with me, that I can’t even feel mentally unwell in peace?

And I know it’s a me problem, because it’s not that my boss doesn’t understand. She’s an enlightened millennial working at a Singaporean media outlet–of course she knows what mental illness is. And I’m sure she knows the dance as well as I do. I’ll say that I’m feeling off and that I need the day off for mental health reasons. She’ll say “No worries, take care!” I’ll turn on Do Not Disturb for the day… and then I’ll spend a restless, unfulfilling day stuck in my own head:

(a) uncomfortable in my own skin now that I’m just sitting here,

(b) way too aware of just how disruptive my mental health is to my life; and

(c) kind of wishing I never took the day off to start with.

When I’m sick with the flu, I take time off and rest. Likewise, when I’m sick with anxiety, I take time off and… overthink?

I don’t speak for everyone, of course. Mental wellness days are positively correlated with better mental health, and it’s good for employers to grant them. Companies may be more amenable to giving time off for mental health breaks now, and even if they aren’t, employees are realising that they need more breaks than the odd public holiday here and there. As a concept, mental health days are good.

So, in the likely event that I take another in the future…

How Do I Have a Good Mental Health Day Off?

Going online yields nothing too helpful. At best, the advice is well-intentioned but doesn’t really tell me how I should spend my day. I get it, mental health matters. I should know, I took a day off work for this.

At worst, the search results yield trite and vague advice. I scroll past three articles telling me to do yoga before realising I have to think through this on my own.

I start by trying to think what I expect out of a mental health day, and stumble upon my first problem. I’ve never actually thought about what I want out of a mental health day. Mental health days off from work feel characterised by more what they aren’t rather than what they are. They’re usually invoked as a last-ditch attempt for respite instead of constructive time set aside for recovery. I don’t know what to do with myself during these breaks because they function as stopgap relief measures; I don’t plan for them. But maybe I should.

As strange as it sounds: If the problem is a lack of planning, should I start planning to take mental health days off?

ADVERTISEMENT

‘Planned mental health days off’ is a mouthful, but it’s not a new concept. We’ve just been calling them other names: sabbaticals, or leaves of absence, or one of another dozen phrases that denote time spent away from work to focus on other matters, well-budgeted for in advance.

Every person I’ve seen on sabbatical has always seemed better off for it. They take time to do whatever it is they want to do–like professors who go on sabbatical to pursue their research interest and promptly fall off the grid for a year–and then come back full of vim and vigour.

Oh, that sounds good. It seems that all roads lead back to the urge to take a sabbatical.

But to take a sabbatical, you generally need to have some measure of tenure at your workplace. It’s not really in the cards for fresh grads and interns, and most full-time workers can’t take them all that often. We’ll just have to settle for mental wellness days for now.

How I’m Spending My Next Mental Health Day

Sabbatical aspirations aside, if I’m planning on revolutionising my mental health day experience, I should change how I think about them. The Platonic ideal of a mental health day (for me at least) involves lots of bed rest and staying in my room quietly, but I’ve found that’s not actually good for my mental health.

Maybe it’s leftover guilt that I haven’t worked through. It’s hard to set aside societal programming. I can’t help but wonder if my colleagues and superiors think I’m skiving off work. In the absence of the authoritative MC, I feel like I have to prove how sick I am, and this extends to how I treat myself on mental health days.

For one, I find myself becoming unusually ascetic. I second-guess myself, and lie down in a dark room because I think that’s what sick people do. I’m so busy with this that I forget to try to get better.

And because I’m so fixated on how I ‘should’ be acting, I don’t leave myself a path to get better–things like getting out of the house, meeting up with my friends, or, fine, doing yoga. I might not even necessarily have to take a day off work to tend to my mental health; I might ask to take more breaks, or to take a lighter workload for a few days. It’s all about what works, really, because there’s plenty of ways to care for yourself.

At least I know I’m not the only one, because it feels like unnecessary shame and guilt are part and parcel of the Singaporean experience. But if we’re going to be more mental health-literate, and create a more flexible, comfortable work environment, then we need to be okay with different approaches to mental health issues.

A mental health day may not necessarily be spent lying down in a dark room, and that’s alright. Substance over form. It’s important that we prioritise feeling better over looking better.