Top image courtesy of Inch Chua.

The naming of things holds an almost mystical power. I would know since my name is Inch, and sometimes I wonder if I grew into the embodiment of this measure or if my likeness was bestowed upon me with the name.

As a species, we name things for various reasons: to facilitate communication and acknowledgement, to categorically give them significance and recognition, and even to impose ownership and control.

ADVERTISEMENT

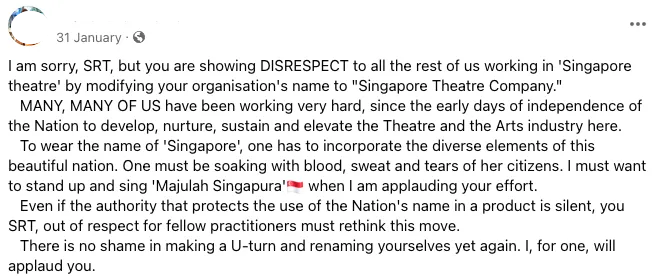

So, what’s in a name? The recent uproar following the transition from Singapore Repertory Theatre (SRT) to Singapore Theatre Company (STC) is a prime example of the peculiar importance of a name. The collective outcry, ranging from dismay to outright indignation, struck me as a curious spectacle—a blend of genuine concern and comedic farce.

For context, here’s the initial story of the rebranding as covered by the national broadsheet. The SparkNotes version is that the SRT has rebranded as the STC to mark its 30th anniversary. The name change reflects the company’s ambition to gain international recognition and move away from the outdated term ‘repertory’, which no longer accurately describes its operations.

The rebranding aims to refresh its image and better represent Singapore’s theatre scene globally. Additionally, the change allows STC to more accurately encompass its wide range of activities, including corporate and educational programs, under a new Centre for Creative Learning.

A fiasco broke out not long after, and every sector of our arts community—from illustrious icons to the ignoble idiot—has risen to opine on the matter, professing their ‘hot takes’ on their social media soapbox.

The controversy has birthed hashtags like #WeAreSingaporeTheatre, spawned petitions, and even led to the formation of informal communal alliances, all united in their resistance against a name: Singapore Repertory Theatre Company.

Following the backlash, a reconsideration of the name change was released and the revert has been officiated today.

I, for one, strongly disagree with the call to revert.

Full disclosure: I am currently an associate artist at SRT, and I’m fully cognisant of how this op-ed could be perceived. Being affiliated with SRT has allowed me to witness firsthand how it has impacted the team. It’s heartbreaking to see resources that could have been used to improve and push projects being diverted to manage this controversy.

People forget how much of a logistical and administrative nightmare it is for any company to undergo a rebranding—not to mention the administrative hassle and cost involved in changing signage, websites, publicity materials, official documents, etc.

Admittedly, when I attended my first team meeting where they shared this colossally important news, I found the announcement profoundly anticlimactic and didn’t see what the fuss was about. I genuinely accepted their reasons for a name change and fully agreed that the former name was not representative of the company culturally or functionally. I concur that the new name strategically streamlines the company’s branding, too.

However, the mean-spirited attacks on STC have been disheartening. They affect the team’s morale and hinder the ability to produce meaningful work. What seemed innocuous to me was clearly not to some of my peers, and I sorely underestimated how this news would be received.

Somehow, this debacle paints SRT as the big bad corporate wolf, hijacking the title of ‘Singapore Theatre’ from all the hardworking, true artisans of our revolution. And according to some, they must be stopped.

ADVERTISEMENT

But in all seriousness, I do recognize the valid points raised by critics. The importance of preserving historical and cultural legacies, the need for inclusivity and representation—these are not trivial matters. They are the backbone of our vibrant theatre community and deserve our utmost respect and consideration.

However, is it really about the name, or are we just grappling with something else here?

Representation and Authenticity

The contention surrounding STC’s name raises the question: Can any one entity ‘hijack’ the entirety of a nation’s theatrical expression? Is it even possible?

This debate mirrors broader philosophical quandaries about representation and authenticity, and rightfully so. Anyone familiar with the Singapore art scene could tell you the depth of how colloquial SRT/STC’s body of work is. Which, in all honesty, isn’t very deep.

But the magnitude of this outcry highlights a deeper existential unease plaguing our community—the fear that the individual and collective contributions of a theatre community might be overshadowed by a monolithic identity.

Have we given in to this fear? If not, why are we acting like we have?

You would think this is a textbook conclusion any mature practitioner would know and wouldn’t need to justify. Just as no single sound can capture the essence of Singapore music, no single theatre company can claim to represent the diverse mosaic of our national identity.

But here we are, again, stuck in this juvenile, meaningless exercise of quantifying ‘Singapore Art’ and throwing labels around. Have we really not graduated from this mentality?

Does the name of one company truly have the power to undermine the rich, varied contributions of the entire community? Why are we acting like the name of one theatre company invalidates our contributions, or is this fear itself indicative of a deeper insecurity about our place in the cultural landscape? As the Gen alphas would put it: what up with this -1000 aura?

Shouldn’t we, as an (allegedly) mature arts community, be secure about our identity by now?

If anything, this incident reveals SRT/STC as a lightning rod for whatever prior personal grievances people have with them, gasolined with the community’s fears and insecurities about identity. It reminds me of the overreaction to the non-essential artist conversation back in the dark ages of COVID.

Lest We Forget

In 1985, a program called Youth Theatre Singapore (YTS) by an entity known as STARS, helmed by its Artistic Directors, Roger Jenkins and the late great Christina Sergeant, began. This often-forgotten chapter of grassroots theatre trained and showcased the talents of young, passionate Singaporeans.

ADVERTISEMENT

Despite being expats, both Roger Jenkins and Tina Sergeant were beloved fixtures in the local theatre community. STARS was based at TAPAC (Telok Ayer Performing Arts Centre), which was a bustling theatre kampung back then, with mini congregations in the corridors. The Necessary Stage occupied rooms on the same floor; Action Theatre was upstairs, and William Teo’s Asia in Theatre Research Circus was downstairs.

STARS eventually re-birthed itself, and Singapore Repertory Theatre was founded in 1993.

Lest we forget, SRT is very much a part of Singapore theatre and has grown into a company that provides jobs for about 30 full-time staff. Can you imagine keeping 30 people on the payroll? For any arts organisation, that’s no easy feat.

Besides keeping the lights on stage warm, they’ve developed residency programs, provided training to local artists and art educators, and continue to hire local talents alongside international talents for productions. Do these factors not count for anything as far as contributing to the growth or sustainment of Singapore theatre?

Would I like to see more original, local, and maybe experimental works coming out from SRT? Absolutely. But there’s also nothing wrong with programming what a company believes will achieve theatrical commercial success. After all, sometimes you have to put on a crowd-pleaser to keep the doors open.

I believe every artist and organisation has their fair share of tussling between the business of art-making and the art itself. I would never judge anyone or any entity for attempting to find that line of balance for their art-making.

I respect companies that violently experiment and choose works that focus on cultural representation unique to our Singapore identity. I also respect companies that possess the prudence to keep Singaporean art managers and practitioners employed. It would be vehemently unjust to discount them as less Singaporean or lesser in the context of Singapore theatre.

How Precious, One Theatre Company To Rule Them All

The drama of the name change also unveils the tango of virtue signalling within our community, which I find painfully nauseating. Are we really resorting to a pissing contest over the moral high ground?

When the subtext of your speech is, “We make more Singaporean work than they do,” or even, “We decided not to call ourselves Singapore XYZ because we know we could never live up to it,” how magnanimous. Who died and made anyone the arbiter of what Singaporean theatre is and isn’t?

Is an American classic staged with Singapore actors considered a lesser Singapore work? Is a Shakespeare production with a regional cast, executed by a Singapore technical crew and designers, considered lesser Singapore work?

What about an Indian classical play directed by a Singapore director? Or a Singaporean writer producing fantasy or futuristic work that doesn’t cover anything remotely ‘Singaporean’? Or a musical, topically about Singapore but directed by a foreign director? Are we really going to start triaging what is more valuable in the eyes of Singapore Theatre?

Sure, let’s tout works with Singapore cast, crew, creative, and topical relevance as the gold standard of what the Singapore poster child theatre production is. But that can also be painfully myopic, rigid, and limiting in the playground of art creation in one of the most globalized immigrant cities in the world.

That would be the equivalent of me classifying some of my music counterparts as producing lesser Singaporean works because they hired a foreign engineer or producer or co-wrote with others overseas or recorded overseas. If their works didn’t topically discuss anything Singaporean, would they be considered inferior Singapore music?

All I can conclude from all of this is the assertion that the title Singapore Theatre Company carries an unbearable weight of expectation, revealing our collective anxiety about living up to an idealised version of national representation. Yet, this concern belies a deeper truth: no name, no matter how grandiose, can encapsulate the entirety of any artistic endeavour. In embracing this reality, we are invited to bestow names of aspiration rather than encapsulation.

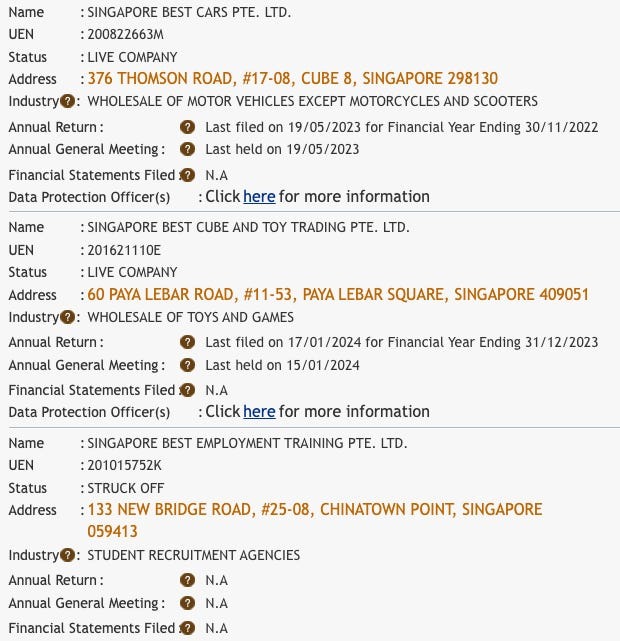

Should I get offended that a chicken rice store is called Singapore Best Chicken Rice? How dare it have the gall to represent all chicken rice and call itself the best. Should I tell these barbarians to change its name because I know which chicken rice store is the actual best? Should I feel offended on behalf of all the chicken rice stores that pre-dated them and built the Singapore hawker scene with their family recipes?

I wish so much for us to transcend petty squabbles over names and instead focus on the essence of our work—the creation of unique, original art that speaks to the soul of Singapore.

Rather than succumbing to the impulse to police titles, we might consider making better use of our time by holding ourselves accountable to the lofty ideals such names aspire to represent.

Life is Performance Art

Names, after all, are but symbols—tools we use to navigate the vastness of the human experience. They hold power only insofar as we grant them significance.

By all means, there’s no issue with sharing one’s grievances and ailments. But perhaps, just maybe… consider how this truly reflects on us and the values we perpetuate.

I am for the cause of creating authentic, unique, original Singapore art—whatever that means. And in an alternate timeline, it would have been a far better strategy for the collective cause to hold the Singapore Theatre Company accountable for the responsibilities of holding a title as such.

I cannot tell you how unprogressive it is to be screaming, “Limpeh offended, so you must change your name.” Why demand a name change when you can demand more representative works? What muscles are we exercising with our actions? The muscle of insecurity or constructive engagement?

That being said, STC has decided to revert back to its old name, SRT, after engaging with the community and empathising with those who felt disrespected. Discord of any kind would not serve the local arts ecosystem, and SRT values fostering goodwill and tight-knit ties.

Although it’s personally not how I would have liked the cards to have fallen, I can respect their desires to mend relationships, showing a willingness to listen and the humility to adapt based on feedback. A virtue rare in our landscape as well. While names are significant, the true essence lies in the art created and the community it rallies.

Life is performance art. I look forward to how we will all remember and re-account all of this.