Top image: Stephanie Lee / RICE file photo

On February 23rd, posts began circulating on social media, voicing concerns over a set of slides from the Ministry of Education’s (MOE) Character & Citizenship Education (CCE) school lessons. These slides—which aimed to teach students about the ongoing situation in Gaza—were eventually leaked to the public, spurring further outrage on an already dicey topic.

Israel’s war on Gaza is a catastrophe that continues to have a far-reaching emotional impact worldwide. The death toll now stands at over 30,177 Palestinians killed in Gaza and the Occupied West Bank, on top of about 1,139 killed in Israel. But it’s considered a delicate subject to broach in Singapore on grounds of potential public disorder. Signs and symbols related to the conflict have been banned; gatherings and protests of any form have been disallowed and subjected to police investigations.

ADVERTISEMENT

How has this episode of the leaked CCE slides affected Singaporeans? Could it cause the authorities to clamp down harder on discussions on sensitive issues? Or might it be a watershed moment, prompting them to provide more avenues or guidelines for such discussions to take place?

The Slides That Started It All

It all started with multiple individuals sharing screenshots of conversations with their children regarding a recent CCE lesson at school discussing the situation in Gaza.

Before long, these conversations were being shared and reshared, with others leaping into the fray to add their thoughts.

Singaporean actress and radio DJ Vernetta Lopez, who has been vocal about the conflict, reposted one such Instagram Story from a parent who was informed by her daughter that during the lesson, there was a slide that read, “Hamas does not believe in Israel as a nation and wants the total destruction of Israel.”

When the parent called the school, she was allegedly told that the slides were issued nationwide and “are not editable by teachers”.

Several teachers RICE spoke to confirmed that schools have been issued fixed sets of slides to share among upper primary, secondary, and junior college levels. While the lessons themselves are compulsory, schools are free to implement the broader lesson format as they deem fit. According to them, some schools had the CCE sessions conducted by the school principals during assembly, while others had teachers conduct the lesson in individual classes.

For all the suddenness of the outrage that they have caused, these CCE lessons did not emerge from a vacuum.

As early as November last year, there were discussions for lessons on the conflict to be held in schools. At that time, Dr Mohamad Maliki Osman, Second Minister for Foreign Affairs and Education, said that as educational institutions engage students in understanding global issues, they will “continue to emphasise Singapore’s multicultural context and the importance of preserving our precious racial and religious harmony”.

He said that schools here provide a safe environment for students to “engage in civil, respectful and balanced discourse and allow different opinions to be voiced and discussed objectively”.

ADVERTISEMENT

Judging by the reactions of students, parents and teachers online—as well as people RICE spoke to—it seems that many students felt they were unable to do so during the CCE lessons they sat through.

Good Intentions, Bad Execution?

As word about the CCE lessons spread, public outcry quickly materialised on social media. On Saturday, February 24th, MOE’s statement on the matter amassed a whopping 3,058 Instagram comments within a span of 20 hours.

These comments were largely critical in tonality, reflecting a range of concerns from both citizens and parents.

‘Intellectual dishonesty’ was raised, with many accusing MOE of glaringly omitting critical facts about the conflict—including the historical context before October 7th, the scale of the attacks, displacements, and civilian deaths currently being perpetrated by Israel in Gaza. It was pointed out that other recent developments, like the International Court of Justice ruling that it’s “plausible” Israel has committed genocide, were not included.

Beyond this, a common criticism emerged around the lack of open consultation between MOE and parents. Several parents expressed that the absence of an ‘opt-out’ option meant they had not been given a fair or open choice about whether their children would be exposed to the teaching material—even though sensitive topics such as sex education typically have these safeguards in place.

A substantial proportion of the commenters asked MOE why—in light of the mounting and highly visible backlash it was receiving—it did not make the slides available to the public. Surely, they pointed out, this could only help the situation by allowing parents to verify the content for themselves and independently quell their worries?

It didn’t take long before several public advocacy figures began weighing in on the situation. Assistant Professor Walid Abdullah, host of politics podcast Teh Tarik with Walid, created a social media post supplementing factual information missing from the slides.

Heckin’ Unicorn lent their prominent LGBTQ+ platform to the affair, while speaking up about the importance of intersectional allyship. It was eventually Plan B, a local current affairs podcast, that took the step of publishing a leaked copy of the primary school slides alongside a three-and-a-half-minute analysis of the content.

Outside of social media, some parents turned their feelings of outrage into concrete, coordinated action by writing to MOE and individual schools, using open letter templates available online. Apart from the abovementioned concerns, these parental letters questioned why there was even a need to bring such a potentially divisive topic into classrooms. Parents wondered if examples from local history might have been more appropriate and perhaps more familiar for teachers to handle confidently.

ADVERTISEMENT

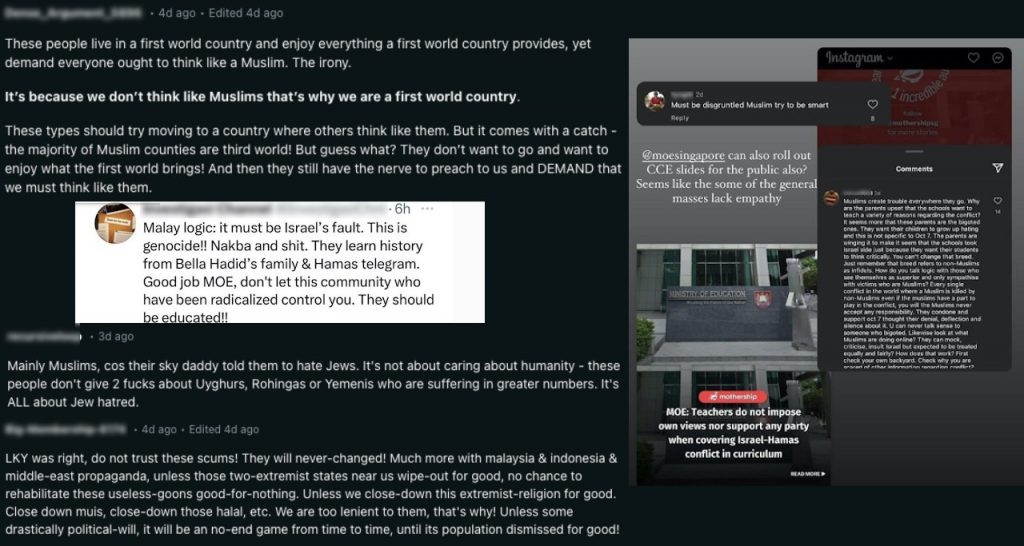

It is perhaps worth noting that in the wake of this entire incident, there have been several waves of social media comments on the topic of radicalisation among the Malay-Muslim community.

These comments make sweeping—if not outrightly bigoted—generalisations about this particular demographic while also implying that they alone are responsible for the backlash to MOE’s actions.

MOE’s full response to the CCE furore arrived on Sunday, February 25, when CNA released an interview with Education Minister Chan Chun Sing.

In it, he reiterated the aims of the CCE lessons for students: To help them process emotions, reflect on safeguarding Singapore’s multiracial harmony, learn to verify information responsibly, and appreciate a diversity of views while conducting respectful conversations.

When asked why the educational package did not include events that happened before Oct 7, Minister Chan said: “Our CCE curriculum and teaching do not depend on it being a running commentary because we are not teaching history or current affairs. But we want to extract from the situation what is the news that our students should be aware of.”

It is unclear at the time of writing if MOE plans to engage with parents any further on the issue.

Discomfort in the Classroom and Home

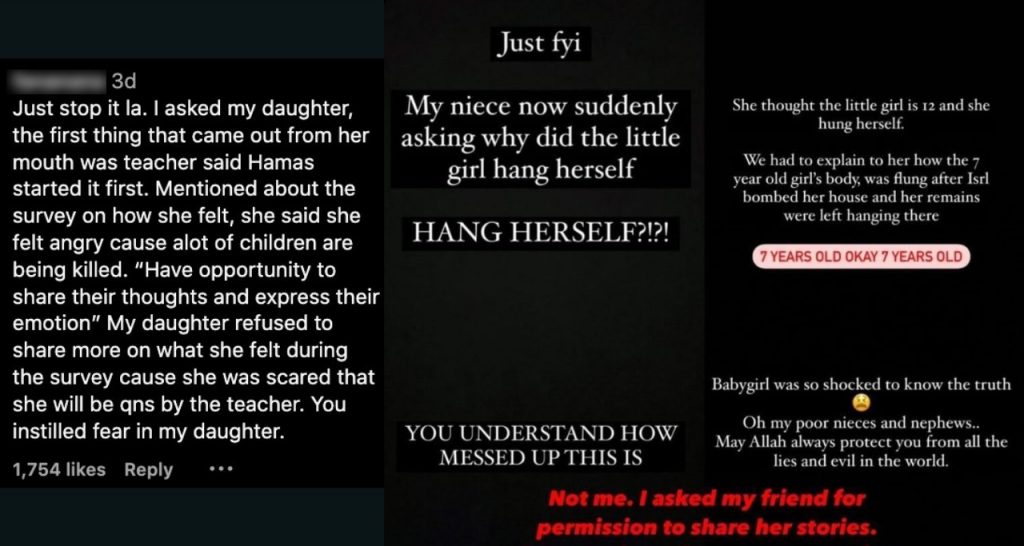

It is undeniable that the events of the last week left an indelible impression on parents and educators. On the parents’ side, some have experienced worry for the emotional well-being of their children who returned from the CCE lessons feeling upset.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nur Hafizah, 36, is one such parent. She shares that her daughter, who’s in Primary 5, felt angered by the “one-sidedness” of a pre-CCE lesson talk given by her school’s principal.

“She came home and complained to me; that’s how I found out. She was so mad. She said, ‘Mum, my principal is so unfair. She said everything that Hamas did but didn’t say anything that Israel did!’”

A few days later, it was followed up by a Form Teacher Guidance Period in which MOE’s CCE slides were shared. Nur’s daughter told her that tensions were apparent during the lesson itself, as students responded with visible discomfort and even argued among themselves when the slides were shown.

“Many of them said the class was chaotic, and the teacher didn’t know how to react. Afterwards, the girls in the toilet were all ranting.”

Nur adds that this situation eventually led her and other parents to take action together in the spirit of wanting to help and protect their children: “Enough of [the children] went home to their parents feeling unhappy. That’s how a group of mums came together to send an email to the principal.”

Other parents who spoke to RICE mentioned how their children reported being unengaged during the lesson. Instead, they came home to ask their parents to clarify the conflict.

“I asked my son what he felt during the lesson,” offers Umairah*, a 37-year-old mother to a P5 son.

“He was quiet for a while and then said, ‘I didn’t feel anything.’ Later on, he asked me, ‘Mummy, can you explain to me what’s happening in Israel and Gaza?’”

Umairah wonders if her son’s teachers had been sufficiently prepared to conduct the lesson. Teachers, on the other hand, are expressing concern about the necessity of presenting slides that lack comprehensive historical context.

Olivia*, a 33-year-old secondary school teacher, says that although her school has not conducted the CCE lessons yet, what she has heard from other teacher colleagues about their experiences makes her feel nervous.

“I’m a bit apprehensive on how to conduct the lesson as we are supposed to follow the slides totally,” she says.

“Some of my kids are passionately pro-Palestine while others are totally indifferent to what’s happening. I would have hoped that the session can at least make the indifferent ones feel a bit more interested to learn more about the situation.”

Others fear their integrity as educators may be compromised by pressure to present omitted material to students on the basis of ‘neutrality’. Linus*, a 27-year-old teacher in a secondary school with a large Chinese student population, concurs.

“As a humanities teacher, it is literally our bread and butter to teach our students critical thinking and to get all their facts straight before passing judgment,” he says.

“The fact that the slides omit key information before October 7th and, in fact, encourage students to isolate the incident and take it out of context is an act of intellectual dishonesty. Frankly, I think it’s an insult to both teachers’ and students’ intelligence.”

Linus also adds that as an educator, he does his best to stay within set boundaries while still prompting students to think critically and even-handedly about the topic.

“While I’m afraid to deviate too much from the slides, the final lesson delivery and what I say is still up to me. To that end, I’ll do my best to get the students to put themselves in the sufferers’ shoes in an attempt to generate empathy. I’ll also provide a list of resources encouraging them to understand the full timeline and decide for themselves only after understanding all the facts.”

The Aftermath: Anger, Anxiety, and Apprehension

When it comes to the impacts on students themselves, it is true that MOE’s policy stresses concern for “the emotional well-being of students” while also outrightly assuring parents that they “do not poll the students on their beliefs”.

But despite these good intentions, there have nevertheless been anecdotal reports of children feeling negative emotions in response to the slides.

Nur, an upper primary student, is one such student. She felt both annoyed and angry in the classroom due to what she believes was an unfair coverage of the issue.

“When asked to rate our feelings, I wrote 5, which means ‘very angry’. My friend then said, ‘You angry for what?’ And that made me even more angry.”

Although she did not feel afraid within the classroom setting, some of her classmates did—the lack of open and transparent dialogue around everyone’s viewpoints felt like a potential spark for conflict.

“For example, if among two friends one supported Palestine and one supported Israel, [my friends] said that they were scared that the one who supported Israel might bully the other.”

Some parents are also left questioning how effectively the CCE slides communicated the most fundamental moral message to children: the need to live in harmony and peace.

Charmaine Seah-Ong, 40, a mother of three, shares that she has such doubts—particularly with how the slides communicated themes pertaining to accountability and retaliation between different parties in the conflict.

Perhaps the biggest parental concern is that the CCE slides, through a narrative of omissions, might diminish students’ exposure to diverse perspectives. This limitation could, in turn, restrict their ability to think critically and form independent opinions from a wider pool of evidence.

Some wonder if this might leave students ill-equipped to make sense of future world events, as they have not been exposed to the necessary skills of reasoning and judgment-forming.

As Charmaine puts it, she disagrees with the materials’ implicit assumption that children would not be able to exercise high-level reasoning skills if given the chance to do so.

“As institutions of education,” she says, “please do a better job of presenting the entire suite of facts related to this war and not a glossed-over version. Our children are smart; they are wise. They deserve to be able to form their own decisions based on the truth.”

“I’ve had conversations about what’s happening in Palestine with my girls, who are aged seven and 10, and they are perfectly capable of handling the information with maturity and sensitivity if given the opportunity to process and make sense of it properly.”

Division or Dialogue?

So, what to make of this whole affair? MOE’s actions can be taken in good faith—they stem from a genuine desire to promote level-headedness on a global issue that’s drawing passionate reactions nationwide.

But when all is said and done, sentiments on the ground leave doubts about the efficacy of this ‘say less, not more’ approach. It leaves one to wonder: Does pruning away information about one side of a debate promote a deep and lasting peace based on mutual recognition and respect for differing views?

From what we’ve seen and heard, at least, it would appear that the overall effect has been quite the opposite. It generated further unhappiness and dissatisfaction when parents, educators and students felt that their views had not been adequately acknowledged.

In the grand scheme of things, perhaps MOE’s approach has also removed a chance for young Singaporeans to practice the very values their nation keeps urging them to hold dear: tolerance of difference, empathy, and a willingness to listen to the other in shared spaces.

With reverberations still being felt on the ground among parents, teachers, and students alike, it remains to be seen if these CCE slides have inadvertently fanned the spirit of divisiveness that they were meant to help avoid in the first place.

*Names have been changed to protect identities