Top image: RICE file photo

I have to be honest—I sometimes put on an accent when I speak with foreigners. Yes, I’m one of those people.

It’s curious. I disassociate, hear myself doing it, and cringe internally. But my mouth just drones on like it’s not connected to my brain.

I’m entirely cognisant that this might rub many Singaporeans the wrong way, but it’s simply what years of code-switching have done to me.

I’m actually not sure what my real accent sounds like. My inner monologue sounds like it went to an elite school; my accent with my family sounds more crude. And when I’m with friends, it differs depending on the group. It’s a subconscious effort to try to fit in as much as possible.

But it almost feels like no matter how you speak, there’s no pleasing people. You’ve got people making fun of (ineligible) presidential candidate George Goh for his pronunciation that sounds like the typical Singaporean uncle. Conversely, sound a little too ang moh and you also run the risk of subconsciously pissing people off.

Take the university student from Singapore who did an innocent street interview in Canada. The subject of the interview was his life in Canada, but comments honed in on his accent.

It sounded like a watered-down Singapore accent, and he tried harder than usual to enunciate. It did sound a little unnatural, sure. But let’s be honest—it’s how we’d speak to a random foreigner in a foreign country brandishing a microphone at us.

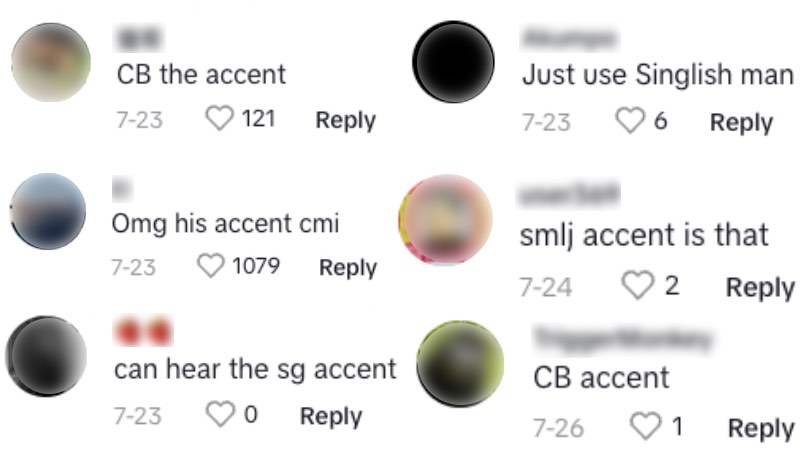

When the video made its way to Singapore, though, people didn’t hesitate to make fun of the poor dude.

One comment branded him “step ang moh”, accusing him of trying to pretend to be Caucasian. Another told him to “just use Singlish man”.

The furore was a little puzzling. Why such hostility towards people who are communicating in the way they deem the most suitable?

A Taxonomy of Atas Accents

Before we delve into the hate people get for sounding too ‘atas’, it should be noted that the Singapore accent isn’t a monolith. Atas sounds different to different people.

For one colleague, who says he went to a “neighbourhood school that’s top 10 from the bottom”, just speaking English was atas enough to stand out and get him labelled as jiak kantang—local slang for a westernised Chinese person.

“I think I definitely felt the line being drawn between native English and Mandarin speakers.”

Then there are those who take on some Western influences in speech.

One of them is influencer and tuition teacher Brooke Lim, who almost sounds like she’s giving a corporate presentation when she speaks in her TikToks. It sounds British, but not quite.

Then there’s our intern, Marc, who hails from the Philippines and speaks with a slight American accent. The archipelago was colonised by Americans (after the Spanish) from 1898 to 1946, so it does make sense that the accent has crept into their vernacular.

In Singapore, Westernised accents stand out, especially if you look Asian.

Marc tells me that being the only Filipino in class for most of his life here, he was singled out for speaking “so chim”—Hokkien for something deep or hard to understand.

“Or they’d just think I’m arrogant or cocky because of my English,” he says.

Even a neutral-sounding accent is enough to get you labelled a tryhard if you’re a minority here.

I gather from a few Malay colleagues that they need to code-switch to good or proper English for work or to be understood by other races. But that has its drawbacks.

“Because of that, some of your fellow minority peers who don’t have the educational privilege or opportunity kinda think you’re snobbish because of how you speak ‘good’ English, so it’s a funny little situation,” RICE’s editor-in-chief Ilyas says. “It’s especially prevalent during National Service, with people from various backgrounds mixing together.”

It’s almost as if the people who get upset at atas accents are taking it as a personal slight.

The way we speak is tied closely to social class, as numerous linguistic scholars have noted.

In Singapore, we’re accustomed to code-switching—and using a more atas accent while others are speaking with a plain old Singapore accent or in Singlish may come across as an attempt to appear superior.

Whether that’s your intention is a whole other matter.

Are We Ashamed to Sound Singaporean?

If there’s one thing I’ve learnt from all those therapists on TikTok, it’s that projection often stems from insecurity.

Rather than dealing with uncomfortable feelings, deflecting them or attributing them to someone else or something else can be the easy way out for some people.

To bring it back to our discussion on accents, it might be easier for someone to gloss over their insecurities over their accent by focusing their hate on someone else for sounding ‘too Western’ or speaking ‘too well’.

After all, even as we hate those with fake accents, we have to acknowledge that many of us do carry some level of shame over our natural Singaporean accents.

We’re used to hearing American and British accents in our media—even our TV presenters adopt these influences. In comparison, our Singaporean accent can sound a little grating or chor lor (Hokkien for rough).

Assistant Professor Luke Lu of Nanyang Technological University’s Linguistics and Multilingual Studies programme tells Youthopia that we often devalue how we speak in Singapore. This stems from the tendency to attach markers like intelligence and friendliness to accents.

However, there’s no reason to feel lesser because of our Singaporean accent, he says.

“The way we speak English is essentially indicative of the kind of multilingual background that we often come from. It’s not something anyone should be ashamed of.”

Dr Tan Ying Ying, Associate Professor of Linguistics and Multilingual Studies at the School of Humanities in Nanyang Technological University, concurs. In an opinion article for CNA, she defends the Singaporean accent, noting that it is highly intelligible and well-understood worldwide.

In Dr Tan’s experience, Singaporeans taking on fake accents can be a symptom of linguistic insecurity.

She points out a growing number of born and bred Singaporeans choosing to adopt Western accents, which she calls pseudo accents.

They pick it up from the media they consume and usually don’t have an accent coach, so they obviously don’t sound native. That’s how their original accent slips through at times.

But by adopting a pseudo accent, you’re essentially branding your speech variety as inferior, Dr Tan explains.

This insecurity is no accident. Two decades of the Speak Good English Movement campaigns have, despite best intentions, reinforced the idea that Singaporeans speak poor English or an undesirable variety of English, she adds.

In other words, some people deal with their circumstances by actively changing how they speak. Others deal with it by hating on those who fake accents or sound different.

And some people, like Marc, who genuinely sounds American because of his upbringing, are stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Accent As A National Identity

Of course, there are those who hate fake accents because they’re proud of how we speak.

If you’ve travelled overseas, you’ve likely experienced that moment where you hear snatches of speech and know immediately: You’re in the presence of a fellow Singaporean.

After all, there isn’t an exclusively Singaporean look. Unless someone’s toting a Beyond The Vines dumpling bag or wearing a Singapore Armed Forces PT shirt, a Singaporean could reasonably look like they’re from any Asian country.

But the Singaporean twang is instantly recognisable to us.

Without a native mother tongue (Bahasa Melayu is symbolic) forming our national identity, the Singaporean accent is the only thing we all have in common.

In our multi-cultural, multi-religious home, patois and accent are the purest concepts that unite us. Understandably, some of us are fiercely protective of it.

Also worth a mention are those who refreshingly embrace the way they grew up speaking English. Asian actors like Michelle Yeoh, who make no attempts to conceal their natural accents, are trailblazers in their own right.

When she took on the role of Captain Philippa Georgiou in Star Trek: Discovery, her Malaysian accent sparked some controversy simply because people weren’t used to hearing it in a Hollywood film. But publications such as NextShark praised her for it and noted that for Asian Americans, hearing their accent—or their parent’s accent—in a movie like Star Trek was a huge step.

The Oscar-winning actress acknowledged this was “a conscious effort and important” in a Facebook post.

As Dr Tan says, “It is time to own the English language and be proud of what we have made of it.”

“What we need to change is not our Singaporean accent, but our attitudes toward it.”