All images by Nathan Koh for RICE Media unless otherwise stated

Approximately 35,000 film slides, 400 audio tapes, and 25 hours of film footage on reels. Dr Ivan Polunin’s entire archives are all kept in a 30-square-metre room in his Hillview home.

The late Dr Polunin was many things. He was a medical doctor, an ethnomusicologist (a person studying music in its sociocultural context), a scientist, a filmmaker, a photographer, an author and an art collector. Ultimately, he had an insatiable curiosity—he was interested in life and all things living.

Film canisters and audio tapes are stacked up on the many rows of shelves in his home office that he dubbed the ‘toy room’. At first glance, the overwhelming amount of material looks disorganised. Upon closer inspection, everything is systematically arranged and meticulously labelled with dates and locations.

I first stumbled across the archive on the Instagram page @IvanPoluninArchives, managed by his grandson, 27-year-old Kazymir Rabier. The page featured photographs in colour from a bygone era of Singapore at a time when colour photography was not only uncommon but also very expensive.

As a photographer myself, I wasn’t interested in photographs that captured inanimate objects—I was interested in photographs that captured life. And Dr Polunin did just that.

The Method to His Madness

Born in London, Dr Polunin had a foreign eye towards the culture and life in Southeast Asia. But he wasn’t simply a fly on the wall; he was part of the action. He made sure to speak to people and partake in new experiences on the ground.

He had come to serve his British National Service after the war in 1948, working in the hospitals of Malaya and Singapore. At the end of his two-year tour of duty, he ventured into the jungles. He lived with a village of Orang Asli–people from the indigenous tribes of Malaya, doing a health survey of the entire community.

“He would always make sure that he got their consent and that they were happy to have photos taken.” 61-year-old Dr Nadya Polunin, the daughter of Dr Polunin, tells me.

His curiosity led to a research grant to Oxford, where he later attained a Doctorate of Medicine and of Philosophy (MD–PhD), eventually coming back to Singapore as a university professor at the Medical Faculty.

He first started filming with the cine camera, a camera used for recording footage on film reels, from the university, using it to film in colour even before colour television came to Singapore. Between 1952 and 1973, he would document Singapore and other countries in the region in 16-millimetre colour film.

He later bought his own equipment and teamed up with Nadya’s godfather, Tony Beamish, who was the director of Radio Singapore. They made many documentaries together, including work for the BBC with Sir David Attenborough.

After he retired some 28 years later, he actually became busier. He had time to focus solely on his passion and interests: researching fireflies, photography, filmmaking and collecting ceramics. He passed away at 90 from a heart-related illness in 2010.

While his daughters were aware of his extensive film and photography collection, they were taken aback by the sheer quantity of his recordings of indigenous music. He made recordings of many ethnic groups all over Southeast Asia.

“He was interested in so many fields and applied scientific methodology to his subjects of interest; there was a method to his madness,” Nadya’s younger sister, 59-year-old Olga Polunin, explains.

But throughout this huge body of work, one thing remained constant: His family.

The Labour of Love

Dr Polunin’s wife, the late Madam Fam Siew Yin, was his main pillar of support.

According to Asmara, people always wondered how her grandfather could pursue so many passions within one lifetime. What many did not realise was that he did not accomplish this alone.

“[Madam Fam Siew Yin] encouraged him to go after his passions and was often behind the scenes–handling the camera equipment, arranging his trips, managing finances, and even stitching his firefly nets, all while raising a family,” she tells me.

“Without her, he would not have been able to do what he did,” Kazymir adds. “She was very involved in [filming] as well, supporting him whenever she could.”

They showed me a photograph that Dr Polunin had taken of his wife while in the field with him. Recording equipment slung over her shoulder, balancing a boom mic to record audio, and eyes peering into a cine camera.

Even though Dr Polunin was always working, he often brought his family along with him on his travels. On most weekends, he would drive his family up to Kuala Benut in Malaysia to see magnificent displays of synchronous flashing fireflies (a species now extinct in Singapore), even when he was well into his 80s.

“We were in this tiny, shaky canoe, cruising down a river looking for fireflies,” his granddaughter, 29-year-old Asmara Rabier, recalls.

“We were chatting, and Grandpa told me to watch out for the giant, man-eating crocodiles that could reach three metres long!”

Similarly, one of Nadya’s favourite photographs was of one of the many he took of the fireflies. In the vast darkness of the jungle down the river, one tree stood out. Hundreds of fireflies, flashing in synchrony, gathered in a tree whose silhouette is similar to a Christmas tree.

The photograph was not only a depiction of nature’s wonders—it made the cover of a National Geographic issue—it was also a precious memory she has with her father.

As Dr Polunin got older, his body weakened, but that didn’t stop him from working.

“He was always working, even up until the end of his life. He would sit in the chair downstairs, filming the squirrel in the durian tree, zooming in with his video camera from the window,” Olga remarked. “He spent the last 20 years of his life going through his archives and preparing them for us to manage.”

Today, managing the archives is a family affair.

Following his death in 2010, his family cared for the late Madam Fam Siew Yin until her death in 2019. Since then, they’ve embarked on a project left behind by the late Dr Polunin–an unfinished manuscript that he worked on during the last 10 years of his life.

Olga and Nadya subsequently became more involved with the archive, teaming up with the National Library Board (NLB) to digitise some of the films. It’s delicate work. Because of the nature of film, it can get destroyed when it comes in contact with water or humidity.

In 2015, Kazymir made his first foray into the archives through a collaboration with one of Ivan’s colleagues and friend, Dr Joe Peters, an expert in ethnomusicology. Dr Peters took to digitising the audio tapes while Kazymir took charge of digitising the film reels.

Using some of the digitised footage and audio, he even produced a short film about his grandfather titled The Humanist.

A New Chapter

“In the last ten years of his life, he was working and constantly revising a manuscript for a book that never ended,” Nadya tells me.

At that time, it was nicknamed ‘Das Buch’, meaning ‘The Book’ in German, because it contained such a voluminous amount of work. “My father spent so many years writing this book, and after he died, it was just sitting on a shelf, unfinished. We felt strongly that we had to find a way to get his book published,” Olga says.

During an exhibition in 2017 titled Sails off Singapore, a talk about the book came up with historian Dr Kevin YL Tan, who had worked with Dr Ivan Polunin when he first began working on his manuscript. When Olga told him that she wanted to finish ‘Das Buch’, he enthusiastically signed up to help.

Asmara, who specialises in Southeast Asian art, teamed up with Dr Tan and three years after that meeting, the book project kicked off in 2020. Asmara applied for a grant from the National Heritage Board (NHB), which finally got the ball rolling.

Though most of the photos were already chosen by Dr Polunin, there was still the gargantuan task of curating and editing the book’s content to make it more digestible for readers.

“While we tried to stay as close as possible to my grandfather’s original blueprint, the sheer expanse of content at our disposal required us to omit important chapters, such as the one on flora,” Asmara tells me. Dr Polunin had already published two books on botany in Malaysia and Singapore in 1991 and 1997.

While collaborating with Dr Tan on curating the visual material, Asmara had to scan over 1,000 Singapore-related images in preparation for the book.

“Scanning the images and colour correcting is very time-consuming. It made me appreciate my grandfather’s work even more as I found myself in the same room, working long hours as I remember him doing during his lifetime,” Asmara recalls.

It has been two years in the making and will be released in the coming weeks. At the same time, Kazymir has brought an online presence to the archives by publishing Dr Polunin’s work on Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, and their website.

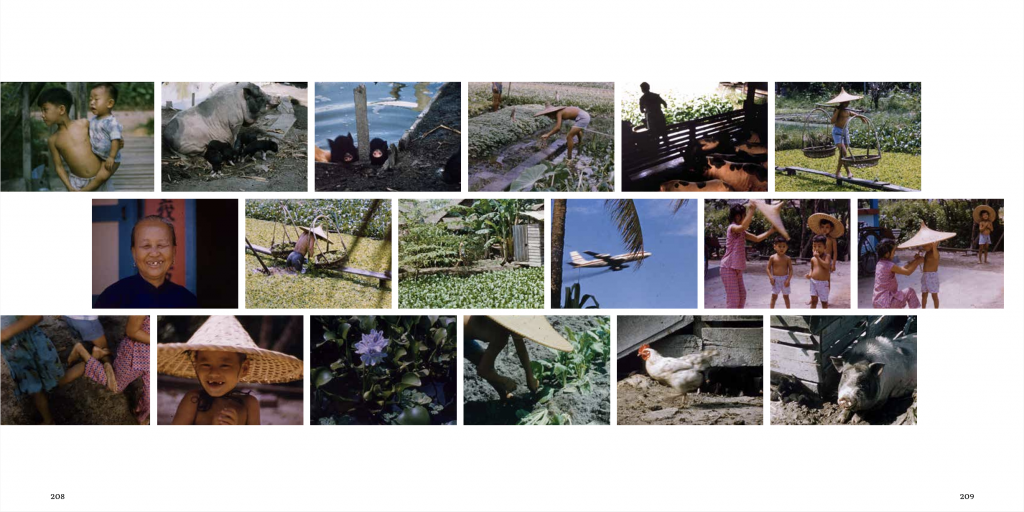

What started as a manuscript from Dr Polunin will finally be completed by his granddaughter Asmara. The book Once Upon an Island: Images of Singapore (1950–1980) Through the Lens of Dr Ivan Polunin, published by Suntree Media, features around 1,000 images of Singapore during a transformative period of pre to post-independence Singapore.

Dr Polunin wanted to address the question: ‘What did Singapore look like in those days?’ He also addresses a more difficult question: ‘What was life like?’

On the Edge of Living Memory

The photographs and films of Singapore that Dr Polunin documented depict a Singapore that looks very different from the cityscape we see around us today. The thing is, what he captured was only part of our recent history.

History is a living thing; without documentation, it dies with those who held those memories. As much as his work might strike a chord with the older generations, why should younger generations be interested?

“I personally believe it can assist younger generations in better understanding our roots, heritage, and the evolution of our cultural identity,” Asmara notes.

Our history is intertwined with our identity as Singaporeans, and Singaporeans need to know where we came from to appreciate where we are and where we are going. The past, present and future are intertwined—and Dr Polunin was well aware of it.

He was interested in people and their lives, making his films and photographs highly intimate. He breathed life into his photographs and films by using colour film.

He knew how important it was to capture life as it is—in colour. Even though it was more expensive than black-and-white film, he felt it was an important investment to make.

In 2009, a documentary titled Lost Images by Moving Visuals premiered, featuring some of Dr Ivan Polunin’s films.

Olga recalls that after it was aired, a group of people with a fruit basket were waiting outside their house looking for Dr Polunin. They wanted to thank him for recording footage of their father when he was on the kelong. They had never seen their father young, healthy and working. When Dr Polunin passed away, they came to pay their respects at his funeral.

The work done by Kazymir and Asmara is for a new generation of Singaporeans to appreciate and allows the works of Dr Polunin to live on. “His book forms a bridge between the older and younger generations,” Nadya says.

The use of social media in this digital age gave Dr Polunin a posthumous audience, nourishing a new generation of curious minds.

The Legacy of Dr Ivan Polunin

The late Dr Ivan Polunin was many things. He was a devoted and loving husband, a father, and a grandfather. But most of all, he was a humanist.

Even though he never became a citizen (though he was a Permanent Resident), he loved and called Singapore his home. He made an invaluable contribution by documenting the lives of everyday Singaporeans.

After the interview, we walked through a micro exhibition of Dr Polunin’s work at Pullman Singapore Orchard, with Olga and Nadya telling me memories of what life was like when they were growing up. Even though Kazymir wasn’t born in that era, he enthusiastically tells me what he learned from his research about life in Singapore through photographs and film.

While we were still talking, two individuals who found Dr Ivan Polunin’s works on Reddit came to the micro exhibition. Kazymir was eyeing them and waiting for an opportunity to share about his grandfather’s works. He approached them and soon after, Olga and Nadya joined him.

They didn’t talk about the photographs or the film; they talked about life at that moment in time. It was exactly what Dr Polunin would have wanted.

His love for people and nature is seen and reflected in his family members. More than a decade since his passing, he still inspires them as they carry on his work, weaving themselves into the fabric of his vibrant legacy.

It’s easy for us to appreciate Dr Polunin’s works without knowing the man behind the camera. If we look deeper and understand what he saw in life, maybe the jaded among us can learn to be curious again about Singapore.

As Dr Polunin said, “Look at the things around you. They look ordinary now. But turn away for a minute, a day, a week, a year, and look at them again—they’ll be completely different. And you’ll wonder what they used to be like.”