In ‘Singaporeans Abroad’, we share the stories of locals who—thanks to living in a globalised world—have found success in different corners of the globe. Whether financially, romantically, or for the pure joy of adventure.

We’ve recently heard from Fabian Low, whose early struggle with an identity crisis while living in Singapore guided his search for a sense of self and led him to his tiny house in New Zealand. Then, there was Jing Rui, whose decades of battling severe eczema and topical steroid withdrawal led her to set up her own skincare clinic in the UK.

Now, we bring you Bella Lee, a social work graduate who’s chosen to counsel Thai orphans for no salary.

All images courtesy of Bella Lee

I’m a 29-year-old Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS) social work graduate. I also haven’t held a ‘proper’ job for the past five years.

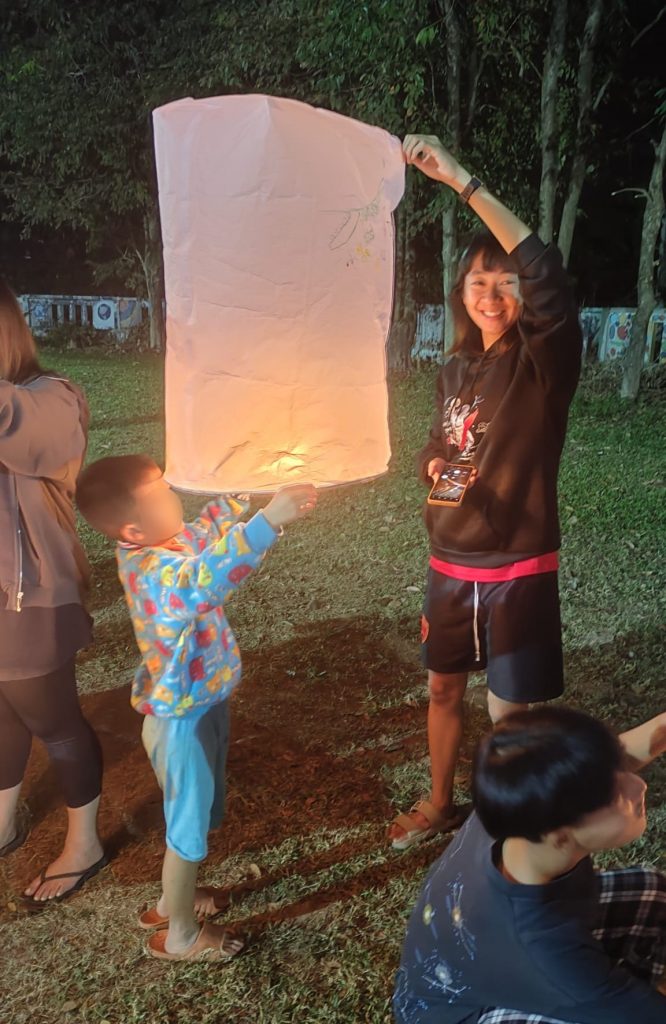

Since June 2019, Care Corner Orphanage in Chiang Mai has been my home. Here, I put my degree to good use by counselling the orphanage’s charges six days a week.

ADVERTISEMENT

Of course, I also help with other duties—checking on the children’s chores, cutting grass, farming, cleaning, updating the orphanage’s social media, and more.

It’s a lot of work, I know, but I don’t exactly get paid. All my expenses are defrayed by generous donations.

Every year, I have to take to social media to raise at least S$12,000—that’s S$1,000 in allowance a month—in order for me to cover my living costs and continue my work here.

The hours are long—I wake up around 5 AM and stay busy all the way until around 9 PM. On my off days every Thursday, I try to rest so that I don’t burn out.

One way I heal myself is to withdraw, and just be quiet. Another is eating good food.

Sometimes, I spend my day off pigging out on hotpot in my room while enjoying a good K-drama. Other times, I might do something spontaneous, like ride my motorbike to the KFC 15 minutes away.

It’s a humble lifestyle, to say the least. But I believe it’s what I’m meant to do.

Growing Up in the Midst of a Storm

I had quite an unstable childhood. I was around eight or nine when a ‘storm’ hit. My father was working in an IT company at the time, which faced legal troubles.

My parents tried to shield us kids from this as much as possible as it unfolded, so the details are hazy to me, I have to admit.

What I do know is that the person accountable for the trouble in the IT company absconded. As the next-in-command, my father was left to deal with the fallout.

He was told to be prepared to be heavily fined or even face imprisonment. While the legal mess unfolded over the next few years, he couldn’t look for a proper job, so he resorted to odd jobs here and there.

The ordeal only ended when the person responsible returned to the country. We received a letter one day that simply stated that investigations were closed. I later heard that the man was sent to prison.

Even though we weren’t in legal trouble anymore, we were in a lot of debt—we even came close to declaring bankruptcy.

ADVERTISEMENT

Before my father’s legal woes, we were pretty comfortable. We’d just moved into a condominium. When things blew up, though, the mortgage became another expense that we had to grapple with each month. We’d also just renovated the place, so we were still paying that expense off.

My parents didn’t want to hold on to the house, but if we’d sold it at that point in time, we would have lost even more money. So their solution was to rent the condominium out for cheap—just enough to cover the mortgage. But that left us essentially homeless.

We moved around from one relative’s house to another, and our family of five often squeezed into one room. Some friends we knew from church also offered us shelter, but we never stayed at each house for very long.

They were all very nice, but we could tell that we were disrupting their lives. A burden. After all, we had nothing to offer them.

It took my family 10 years to finally pay off the debts. After things stabilised, we were able to sell off the condo and move into an HDB flat in Pasir Ris, and it felt like a chapter was closed.

My parents tried not to let the financial issues burden me and my sisters. Eventually, however, it got to the point where the struggles were apparent to us.

We were told not to open the door for strangers, because debt collectors would look for us at home.

Even a $200 check I scored from a good character award at school went toward helping the family tide through the month. To their credit, my parents never wanted to eat into their children’s savings. They promised they’d return the sum to me, and they did eventually.

But there were times when things really took a toll on my parents. I remember my mum showing me her wallet once. There was only about $10 left in it. She asked me, “How? What should we do?”

As a child, what could I do? I simply replied, “Oh, let’s go buy instant noodles.”

Overall, it was very tough, but I think it opened up my eyes. In day-to-day life, people might seem happy but there might be a lot of things that they’re going through. I know this because throughout this period of turmoil at home, I acted like everything was fine at school. How could I tell anyone that we were barely getting by?

On the plus side, I think all the instability made me a very adaptable person. That’s why I haven’t really had any problems adjusting to life here in Chiang Mai.

Finding a Direction

The first time I visited Chiang Mai was in 2012. My school then, Millennia Institute, had organised a volunteer trip there at Care Corner Orphanage.

Established in 1995, the Thai orphanage houses around 80 children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

In Northern Thailand, especially Chiang Mai, drug use and trafficking are big problems. The pervasiveness of narcotics really hit home when I saw kids in poor villages sniffing glue.

Some of the kids—including those at Care Corner—have had their families broken apart by drugs. Sometimes, the parents end up in jail. Or the mum abandons her children to look for a new man.

After asking around, I learned that the home didn’t have a counsellor. This meant the kids didn’t exactly have the tools and support they needed when they faced personal challenges.

I felt moved after seeing the kids’ situations, and I wanted to do something about it.

After our first trip to Care Corner, my friend and I floated the idea of making a trip back here to spend more time with the Thai kids and to help out in whatever we could. With every trip, we learned more about the kids and saw how they lived. These were bright kids, but they didn’t have a supportive environment back in their villages.

Drugs tore their families apart. The more we saw, the more we wanted to return to do more.

I wanted them to know that there was more out there than drugs and help them realise their potential. At Care Corner, the staff would ensure that the kids stay in school and that their needs—everything from haircuts to healthcare—are met. They also organise different enrichment activities for the kids, such as agriculture and raising chickens.

We do have weekly small group sessions where volunteers have bible sharings and church service every Sunday. It’s not just for religious purposes or evangelisation—we see it as a group activity that’s beneficial for their social and emotional development.

Even after the kids graduate and come of age and are technically free to leave, they still get support. They can choose to stay at the home for a small sum to mimic rent in the outside world. While they get a taste of independence, they can still build their personal savings.

We’d make trips back annually. And then one trip a year became two. The trips also got longer. Moving over permanently became the natural choice for me. I knew if I wanted to do counselling work there, I couldn’t keep leaving to return to Singapore. Even staying for three to six months wouldn’t be enough for me to really make a long-term impact on the kids.

While my friend did toy with the idea of staying in Thailand, she leaned more towards working in Singapore. She still visits and volunteers whenever she can and is planning to come back in a couple of months.

The more I volunteered, the clearer it became to me that I wanted to work with children in the future. I made some big changes. The first was that I switched university majors: From business to social work. When I chose to study business, I hadn’t yet decided on a direction in life. It just seemed like the general, practical choice.

As time went on, however, I felt drawn to social work. I wanted to be able to have the tools to help the kids at Care Corner make sense of whatever they were going through and I wanted to be there for them.

Maybe I wanted to be that source of support that I never had in my own tumultuous childhood. As the eldest child, you’re more perceptive. I knew how much my parents struggled, but I didn’t have the tools or resources to deal with the situation. And in school, it was easier to pretend everything was fine.

For the sake of communicating better with the kids, I also decided to learn Thai. I had resisted learning it for the first few years because I had wanted to learn Korean (I’m a K-drama fan). I didn’t think I could handle another language on top of that.

However, I reached a point where I just could not understand what the kids were trying to tell me. I was also frustrated because I couldn’t express myself to them.

I was on a very tight budget, so I turned to Carousell. I hoped and prayed that I would find a suitable teacher, and things worked out better than I could have imagined.

The teacher I found was Christian, as am I, so she was able to teach me some religious terminology. She was also able to give me a special price, knowing that I had a tight budget.

The twist that shocked me was that she was actually a supporter of Care Corner Orphanage and had been here many times. I took this serendipity as a sign that I was on the right path in life.

Thai ‘Sabai Sabai’

Now, I’m fluent in Thai. And when I’m talking to my Singaporean friends, they sometimes remark that I have a bit of a Thai accent when I speak English! I don’t hear it, though.

When I moved over, all I brought was some clothes, a mini electric hotpot (because I love soup), as well as resources and tools that could help me in my counselling work.

Going from a cosmopolitan city to a rural countryside is also a huge change. I do like the slower pace of life here, though. I’ve learnt a lot from my Thai colleagues at the orphanage. Here, they like to “sabai sabai”. If someone asks you how you’re doing, replying “sabai dee” means you’re doing fine.

But the Thai phrase encompasses more than that. ‘Sabai sabai’ is a state of mind: To be relaxed, chill, and generally take things easy.

I’m a Singaporean through and through, so I’m always rushing from one thing to the next, and taking on more than I can handle. Since moving here, I’ve learnt to slow down, to live life the Thai “sabai sabai” way.

I’ve learnt that it’s actually okay to take a break. It’s okay to rest when you’re sick.

Faith in Action

Friends and family didn’t understand my choice at first. They believed that since I grew up in Singapore and studied in Singapore, working in Singapore just made sense.

My own doubts echoed their misgivings. “Why make your life so hard? It’s already hard enough,” I did think to myself. “After all these years of very stormy times, don’t you want some peaceful times?”

But I also had this thought: “Since life has already been so abnormal, just continue lor.”

My father also asked me, “Don’t you want to get married? Aren’t you worried about finances? Don’t you worry about your future?”

Of course, I think about all of these. In fact, I think of these things too much, I’d say.

My mother, on the other hand, was very supportive.

“If you’ve found a direction in life, then you better go,” she told me. “Don’t do something else, knowing full well that there is a reason why you feel this burden for the kids.”

Another of my considerations before making the move was that I wanted to repay my parents for raising me. After graduation, if I’d worked as a social worker, the salary wouldn’t be anything crazy, of course, but it would be alright. And it would be such a good thing to be able to pay them back.

But since I chose this path, I have to be filial in other ways. I try to remain connected with my family through regular video calls. The calls also help to assuage my parents’ concerns—at least a little—when they see that I’m doing fine with the Thai kids here.

I have to admit that I’m a big overthinker. My faith, however, helps me a lot. I trust that when I take care of myself and work hard here, God will also take care of my family. It also helps that I have two sisters back home to hold the fort.

Through all the noise from others—and my own worries—I’m certain of one thing. I’ve found purpose in the life that I’m leading now. I found what I want to do. I want to use my life to support and help the children here. For as long as I can, I hope to continue this work.

Living With Purpose

My counselling work with the kids is done individually, in pairs, or in groups depending on the issue and purpose. Sometimes, they come to me. At other times, I go to them and we will sit somewhere to talk or do activities together.

Counselling is open to every child. I regularly check on their well-being—both physical and emotional. We also talk about their needs and goals for the future.

It isn’t just a one-woman show. During meetings, my colleagues and I often discuss and consult with each other on how we can help each child tackle their issues.

What keeps me going is seeing the fruits of my labour in the children’s lives. But, of course, it’s a process. The joy doesn’t come immediately. Sometimes I only hear of kids’ successes in life a few years after they leave the orphanage.

It can be as simple as hearing that they’ve found a job. Or that they want to return to work at Care Corner to give back.

I remember one child who was very angry and had a lot of hatred in his heart. He had plans to harm others in the home. So I worked with him. I had a few counselling sessions where I talked things through with him to help him process and let go of his anger. When he promised that he wouldn’t execute his plans, I thought, “Wow, good. I’m so proud of you.”

Of course, those working in a corporate job would earn more than me, but I’m not bitter about it at all. I’m just grateful to be doing something I find meaningful.

If we talk about the future and questions like “Are you anxious? Are you worried?” come up, I would say yes, I am slightly concerned.

I sometimes look at my bank account and think: “Can you go up a little bit?”

But I try to think of it positively. Even if I were working in Singapore, it doesn’t mean that I won’t be hit by another storm. All that matters is that I have today, and I’m trying my best.