Singapore’s art scene is in quite the tizzy these days.

First came the National Arts Council’s delayed and awkward response to Sonny Liew’s bagging 3 Eisner awards for the The Art Of Charlie Chan Hock Chye. Then two days ago, former NMP and now regular citizen Calvin Cheng argued that the government should not fund the arts with taxpayers’ money.

His arguments made some sense. The need for critical discourse aside, one can understand why a government body would be hesitant about facilitating any diversions from its own version of the national narrative. Yet when it tries not to embarrass itself (in the case of Sonny’s graphic novel), it’s accused of censorship.

To avoid this conflict of interest, Cheng proposed that funding for the arts should come from the private sector; in other words, from Singaporeans.

There are 2 glaring reasons why, at least in the immediate term, his suggestion is misguided.

Patronage is defined as the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organisation or individual bestows on another. In this case, Cheng is referring specifically to financial patronage of the arts.

Aside from flag day, I can’t recall the last time I made any sort of donation, not least to an arts or heritage institution. And I know it’s not just me.

The Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth’s Cultural Matching Fund, which provides dollar for dollar matching grants for private donations to arts and heritage institutions, took 2 years to raise a total of $150 million. This means that from 2013 to 2015, a maximum of $75 million came from the public. Of this amount, $16 million came from 104 persons.

While $75 million sounds like a lot, it’s nothing compared to the $378 million the government itself spent funding the arts and heritage projects in 2013 alone.

Without government funding, I doubt $75 million spread across 2 years would last very long. We wouldn’t be able to fund exhibits like the Imaginarium, musicians like Gentle Bones, performances such as BayBeats, and everything else from dan:s festival to the Singapore Night Festival. Something would have to go.

Or Singaporeans could dig deeper into their pockets, something that we (including myself) should’ve started doing a long time ago to sustain the arts.

But developing a culture of patronage will require a significant shift in our mindsets.

Arts patronage is sustainable only if everyone gives, and gives consistently. Because of our small size and population, the support of every donor matters immensely. Moreover, we can’t only give when times are good and not when times are bad. This will only serve to make the arts scene even more tenuous than it already is.

We’d also have to give unselfishly. At the heart of patronage is giving for the benefit of others. And so unlike Kickstarter campaigns, those who donate $200, for example, to the staging of an exhibit or event, will receive the same access to it as someone who donates $50, $10, or even $0.

Free-riding will inevitably be a thing. Patrons can’t insist on a private ticketed event, open only to patrons as that would go against the very spirit of patronage. Your patronage enables an event to materialise, but it isn’t your admission ticket.

And so the tough question we have to ask ourselves then is whether we, as patrons, will be willing to tolerate free-riders?

Without government funding, a lot of things will change. There will be some unpleasant social by-products too. But we will need to accept that all this comes with a strong culture of patronage. And in this case, because it’s patronage from all regular Singaporeans rather than just a few select individuals, we know we’re all in it together.

The good and bad thing about being a patron is that one can choose where and what to give money to. While it allows you to donate to a specific cause that you support and believe in, this also means that exhibits which don’t suit your taste will fall between the cracks.

Take Yayoi Kusama’s exhibit for instance. One reason for its sheer popularity is its spectacular and large-scale installations. They’re mostly eye-catching and make for excellent Instagram photos.

In a non-government funded world, an exhibit like Yayoi’s would definitely get the private funding it needs to be showcased. But what about an exhibit that perhaps isn’t as colourful, as Instagrammable, or as spectacular?

Most Singaporeans aren’t connoisseurs of art. Most of the time, we just want something nice to look at, something that will make us go, “Waaaaah”. And so we might just start seeing more and more showstopping, picture worthy exhibits.

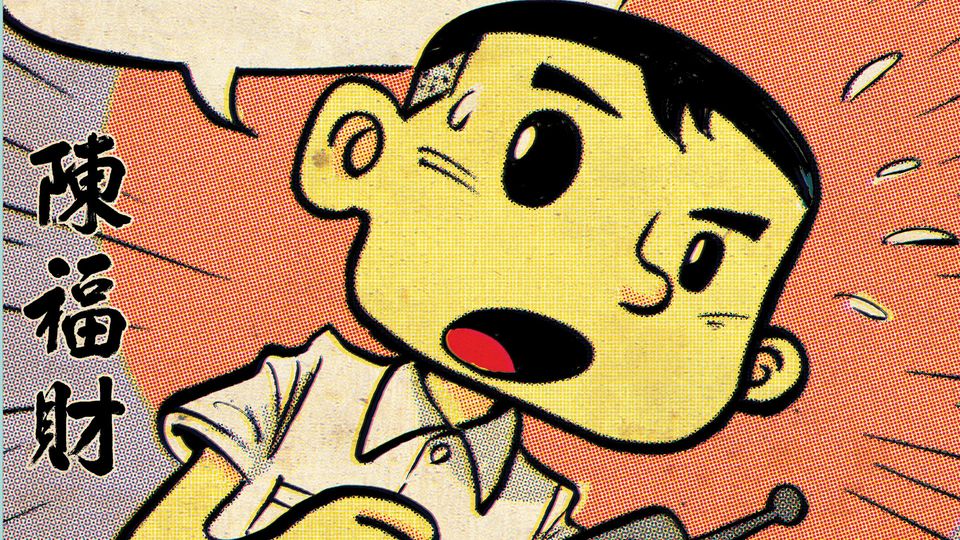

We’ll continue to get more shows like Yayoi Kusama’s Life Is The Heart Of A Rainbow, The British Museum’s Treasures of the World, or Team Lab’s Story of the Forest. But would this also mean less of artists like Chen Cheong Swee and Wu Guanzhong?

By leaving the curation of art open to market forces, we’d get the art most of us want, but potentially at the expense of those that don’t cater to mainstream tastes.

We’d end up with a very narrow and incomplete view of the world and art itself.

What Cheng said was so silly because he neglected to account for how governments continue to use their arts and culture scenes as tools of soft power. This is why the Advisory Council on Culture and the Arts was set up in 1989, and led eventually to the construction of what is now the Esplanade.

The government wants Singapore’s arts scene to be taken seriously internationally, and so it will always be in its best interests to keep funding the arts.

That said, there needs to be a place for artists like Sonny. Back in 2016, he shared a breakdown of costs and profits from the sales and publication of The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye. We now know that for someone who won 3 Oscar equivalents, he only made about $2500 a month.

This is why funding matters, and that artists have alternative sources of financial support should the government prove unwilling. For this to happen, we need to start developing a culture of patronage and a more discerning appreciation of art.

If Cheng’s comment had any merit at all, it would be that he has reminded us how we need to start relying less on the government to keep the arts alive. As has been publicly trumpeted many times, the Singaporean government continues to believe that the arts exist for the purpose of nation building, which is not just misguided, but also boring.

And so I look forward to the day when ‘patron of the arts’ is not just a label reserved for rich philanthropists, but regular Singaporeans too. Maybe then we’ll better learn to appreciate the art we have and play a part in ensuring its diversity, rather than simply seeing art as good Instagram opportunities.

But until that happens, let’s just be thankful that the Government is still funding the arts and not building another casino.