All images courtesy of Ministry of Funny unless otherwise stated.

Haresh Tilani and Terence Chia proudly recall the media launch day of their HOOQ comedy series She’s a Terrorist and I Love Her (SATAILH). It was a Tuesday evening, 21 January 2020—a few months shy before Singapore (and the world) descended into pandemic-stricken chaos.

The launch at a space along Jalan Kilang saw local influencers trapped in a terrorist-themed escape room with half an hour to find a way out.

Organised by now-defunct Singaporean video-on-demand streaming service HOOQ, the edgy marketing was meant to provoke a strong reaction. And it worked. By all accounts, HOOQ’s partnership with Haresh and Terence—the minds behind Ministry of Funny—was off to a strong start.

“I remember the PR company sending invites to these influencers,” Terence, 40, shares in an interview held at their office in MacPherson.

“If I’m not mistaken, it was sent in unmarked packages. The PR company tried to make it look like they were dropping off a mysterious parcel.”

“One influencer got quite spooked by the whole thing,” Haresh, 39, adds with a laugh.

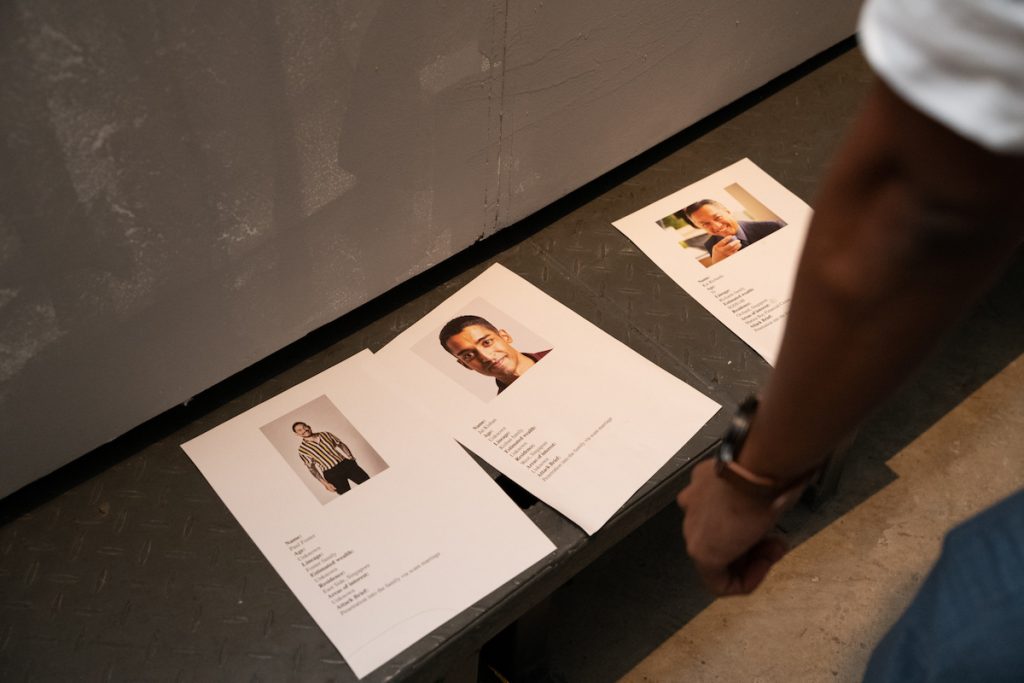

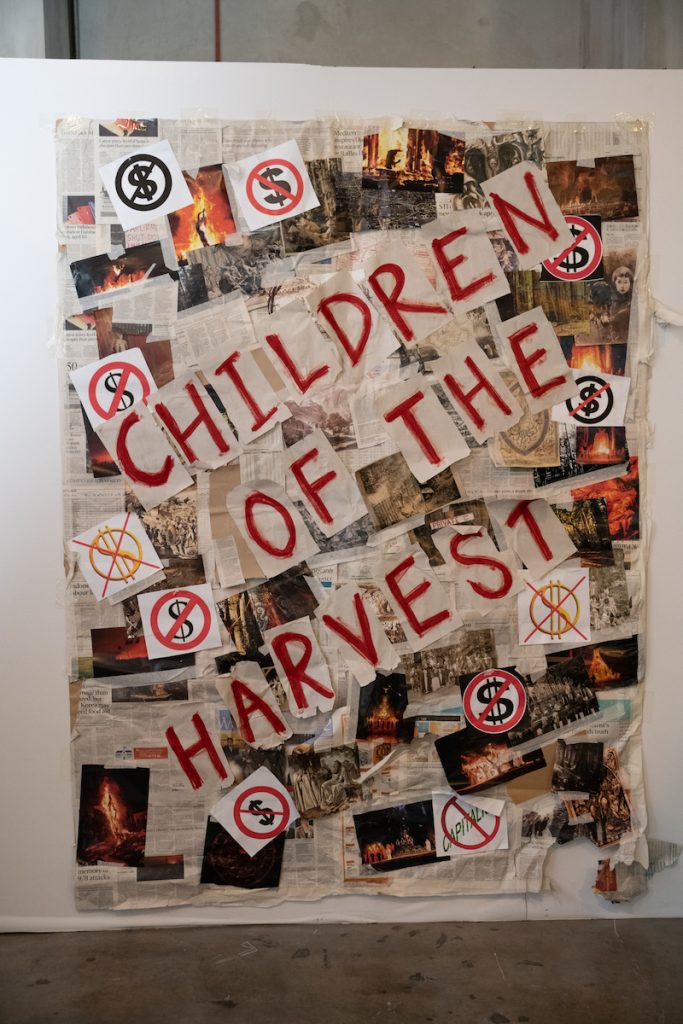

SATAILH is a dark comedy that centres around down-and-out Jo, played by Haresh, who gets into a sham marriage for quick money. His wife, played by Caitanya Tan, is a ‘Children of the Harvest’ extremist planning a terror attack on Singapore. Hijinks ensue.

The first two episodes of SATAILH were screened to guests before the series premiered two days later on HOOQ. Early reviews raved about its local authenticity with plenty of Singlish, satire, sex and raunch.

“This successful partnership with Ministry of Funny is a true testament to the abundance of filmmaking talent in Asia and highlights the need for HOOQ to continue supporting and uncovering the best creatives in our region,” said Jennifer Batty, then-Chief Content Officer at HOOQ.

Months later, HOOQ fell apart. On 27 March 2020, HOOQ announced its liquidation. In its wake, the video streaming platform was taken down as liquidators took steps to recover monies owed to creditors.

It left Haresh and Terence in limbo. With the platform ceasing to exist, so did the show they poured their heart and soul into making.

And since the intellectual property (IP) rights of SATAILH belong to HOOQ, they could not share the fruits of their labour with the world, even if they wanted to.

But it also meant that all remaining monies owed to Haresh and Terence in exchange for producing eight episodes of SATAILH were on hold—indefinitely.

In one fell swoop, Haresh and Terence were S$205,114 in debt with nothing to show for it. And they weren’t the only Singaporean filmmakers who’ve yet to recover the money HOOQ owes them.

From Pilot to Commission

Haresh and Terence, for those familiar with Singapore’s burgeoning podcast scene, are hosts of Yah Lah BUT (YLB), a talk show filled with unfiltered, comedic opinions on current affairs.

Pre-YLB fame, the two were actively uploading videos on their 12-year-old YouTube channel, Ministry of Funny.

The opportunity from HOOQ to produce an original comedy-drama series came in 2018 when the duo started taking content creation more seriously. The annual HOOQ Filmmaker’s Guild seemed like a chance to prove themselves beyond YouTube.

“It was an open call for TV concepts from around Asia. Anyone can apply as long as it’s content that shows what Asia is about,” Haresh explains.

On 31 July 2018, the duo submitted a story pitch for SATAILH, which had seen multiple rejections by other media networks due to its sensitive plot themes. Three months later, they received news that they were among the five finalists in the competition, alongside other regional creators.

As part of the competition, they received USD$30,000 to script and produce a pilot for judging.

After submitting their work, Haresh and Terence soon got the call that changed their lives forever. On 26 April 2019, they were informed that they’d won the competition.

“I still remember that morning,” Haresh recalls.

“Terence told me that Bryan (a HOOQ representative) wants to talk. I had a feeling that we were the winners then. But when we got a call confirming it, I just burst into tears.”

HOOQ: Five Years of Rapid Growth

HOOQ was founded in 2015 as a joint venture between Singtel, Sony Pictures Television and Warner Bros. At its peak, it operated in the Philippines, Thailand, India, Indonesia and Singapore.

Singapore Business Review reported that the deal was worth S$27.6 million, with Singtel owning 65 percent of the joint venture, while Warner Bros and AXN—a Sony Pictures subsidiary—each own a stake of 17.5 percent each.

Over five years and three rounds of funding, HOOQ grew—fast. Under founding CEO Peter Bithos, the streaming platform expanded to a staff count of nearly 250. The company launched at the right time when the likes of Netflix and Amazon Prime Video didn’t have much presence in Singapore.

The former COO of Globe Telecom in the Philippines also led HOOQ to earn more than $30 million in annual revenue through a subscription base of 100 million registered users and 10 million paid subscribers.

HOOQ’s exponential growth naturally caught the interest of Singapore media ministries. A Variety article reported that the Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA) would be teaming up to develop local content for distribution in Southeast Asia and India.

Mediacorp also signed content and subscription deals with HOOQ to distribute cross-company content to audiences across Asia. SATAILH was one highlighted series—and so was Anthony Chen’s acclaimed Wet Season, dubbed a ‘HOOQ original’.

In Time for Christmas

Things started moving at warp speed. Commercial terms were drawn up, timelines scheduled, actors roped in, film crew recruited, writers hired. Contracts were signed.

“Shortly after finding out we won, we were told we had to deliver all eight episodes by October 2019. It was a crazy fucking timeframe,” shares Terence. He posited that the platform wanted something to push and promote in time for Christmas.

Apart from the tight delivery deadline, the duo were also trying to negotiate the payment schedules dictated by HOOQ. There was an agreed budget of S$512,785, which would be paid in tranches.

“It’s 15 percent on signing the agreement, another 15 percent on the first day of principal photography, a further 15 percent when HOOQ receives a rough edit of the first episode of the program, and then a final 15 percent on the final delivery of the first episode,” Terence recalls.

“Once all the episodes are delivered, we can invoice the next 20 percent of the payment. The final 20 percent will be submitted four months after that.”

‘They’re Not Going To Disappear’

Haresh and Terence weren’t comfortable with the payment schedule, and for good reason.

With HOOQ’s payment tranches, the two knew they would reach a point where it was going to take a while to compensate their freelancers. Most freelancers work on 30 to 45 days payment terms, and Haresh and Terence wanted to fulfil their financial obligations.

Plus, a delay in signing the contract would lead to further delays in payment disbursement.

“We were under pressure to meet a tight timeline, and if we didn’t agree to the terms, the deal could have fallen through, resulting in lost opportunities and expenses,” Terence says.

They tried negotiating a more favourable term but were told by HOOQ executives that they would have to talk to Singtel’s lawyers.

Haresh remembers discussing the issues with Terence at the food court of 313@Somerset, just a few hundred metres away from Singtel’s iconic Comcentre headquarters along Exeter Road.

What set their mind at ease was knowing that HOOQ was partly owned by reputable companies like Singtel, Warner Brothers, and Sony.

“We told ourselves that it should be okay. They’re not going to disappear,” Haresh tells me. He recalls gesturing to the general direction of the Singtel building as assurance.

With few resources to hire a lawyer to negotiate terms with Singtel’s legal team—on top of a tight project margin—Haresh and Terence accepted the terms. It would be an uphill battle to renegotiate the terms too since the same contract was previously offered and accepted by other competition participants.

Even in hindsight, they don’t have any regrets about not getting a lawyer. It just wasn’t possible at that point in time.

The Thrill of Delivery

“Until the point of liquidation, it did feel like they wanted us to create a good show,” Haresh muses.

For Haresh and Terence, it felt like they were working with network executives who genuinely wanted to make a “kickass show”.

The duo was determined to make it work. It’s rare enough to find a company that would so willingly greenlight a project like SATAILH that many other networks felt was too controversial to air.

The filming of SATAILH also gave the duo an inside look into what a production at this scale feels like. The two worked with talented production freelancers, actors (Munah Bagharib, Benjamin Kheng, Noah Yap, Caitanya Tan, and more came on board), artists, and even a crew that understood the daunting task: Completing eight episodes in a month.

“The hardest part was managing the different personalities on set,” he adds. “But we took it all in our stride because this was going to be our big break.”

On 23 October 2019, Haresh and Terence officially wrapped production after 30 days.

“Just the emotion of ‘We did something amazing together’—it was indescribable,” Terence recalls. “We felt like it was something special.”

Haresh recalls sitting in the car he rented for the shoot at 4 AM that day. “When I parked the car, I burst out crying, and I just couldn’t stop,” he says to the peals of laughter from Terence.

“I was probably driving home wiping away tears too while listening to Hans Zimmer,” Terence adds.

At that point in time, there was no reason to believe HOOQ was about to head into financial ruin.

After all, there were discussions with HOOQ about how there would be a second season. Haresh and Terence even met with the network executives to discuss how to continue promoting season one while brainstorming story ideas for the next season.

“That was 26 March 2020—a Thursday,” Haresh confirms, referencing his Google calendar entries. “I was in the midst of preparing the storyboard deck for season two when it all came crumbling down.”

The Liquidation

On Friday, 27 March 2020, at 1:30 PM, HOOQ and Singtel announced the liquidation. About 240 people employed by HOOQ across Asia were let go, including around 98 in Singapore. Singtel stepped in to take over financial obligations to pay the axed employees’ payroll.

According to filings with ACRA, there was a total accumulated loss of US$220.8 million and liabilities of US$70.8 million. Despite the additional backing from entertainment giants Sony Pictures and Warner Brothers, HOOQ could not keep up with larger, established rivals like Netflix.

HOOQ cited a competitive landscape: “As a result, HOOQ has not been able to grow sufficiently to provide sustainable returns nor cover escalating content costs and the continuous operating costs.”

HOOQ’s funds had dried up dramatically when COVID hit—talk of investments quickly shut down when risk appetites changed. Their pockets just weren’t deep enough to continue purchasing original content and fund content marketing to drive usage.

“By the time we got to late March, it was pretty clear that nothing was going to happen in 2020. So we were faced with putting another US$60 million to US$70 million into the business to just keep it going,” Bithos—now the CEO of Seek Asia—shared at a Tech in Asia Conference.

“March 26 was one of the worst days of my life,” he mentioned.

The day that Haresh and Terence met with network executives about future prospects was the same day Bithos broke the news to his team that HOOQ was shutting down.

House of Cards

There was no time to process their emotions. The first thing Haresh and Terence did was send out the last invoice for the remaining 20 percent payment owed to them.

The pair were pretty sure they wouldn’t be paid in the end. Still, they insisted on leaving a paper trail as evidence that they tried to recover the monies owed to them.

At this point, HOOQ owed the two S$205,114. Since the pair would not see this amount until four months later, they had to take other measures to ensure the freelancers, crew, and actors they hired were duly paid.

“We had to take personal loans from our family to the tune of S$180,000, split between Terence and me,” Haresh says. “We were okay with taking a loan because we trusted the money would eventually come in.”

As of our interview, Haresh and Terence are still paying off their personal loans.

Still, even after receiving news about the liquidation, Haresh hoped they would be paid what was owed to them.

“I remember I saw the press release,” Haresh adds. “And I thought, you know, we had a contract what. They have to pay.”

He admits to knowing little about the process of liquidation then. “It was a lot of us learning and talking to people, really understanding what this means, and what recourse we had.

Passed Around Like Hot Potato

As it turns out, there was little anyone could do. A clarification email sent on 30 April 2020 by Bithos confirms as much.

Haresh and Terence would learn that they had to deal with HOOQ Digital Mauritius Private Limited, located in Mauritius, an island nation off the continent of Africa.

“Because HOOQ Singapore is now in liquidation, it cannot pay HOOQ Mauritius and, therefore, HOOQ Mauritius does not currently have the funds to pay you (or any other of its obligations),” Bithos wrote.

In the same email, Bithos explained that “HOOQ Mauritius is a separate entity from HOOQ Singapore. Having said that, it is a wholly owned subsidiary of HOOQ Singapore and relies on HOOQ Singapore for its revenue, which in turn, enables HOOQ Mauritius to pay you.”

“This is not an uncommon structure with many media companies who produce content for multiple geographies,” he adds.

At that time, it was the height of the pandemic with worldwide lockdowns. Haresh and Terence couldn’t fly over to Mauritius to physically present proof of debt to lawyers there—they had to do everything online.

“We had to pay US$1,200 just to file the proof of debt to the courts in Mauritius. We couldn’t just hand over our invoice as is—it had to be notarised. After that, we DHL-ed it over to the island. It was a whole thing,” Haresh tells me.

They then sent multiple emails to their contacts over at HOOQ only to have them mostly go unanswered or replied late. And when they did respond, they were greeted with a boilerplate response.

Bithos could not offer additional clarification. “I cannot legally speak specifically to HOOQ Mauritius’ status with external parties until specific legal processes transpire,” he stated in the email.

“We were like a hot potato that got passed around as people see fit. First to legal, then to another person in another department. No one would help us. Or rather, they couldn’t because of the liquidation process,” says Haresh, frustration evident in his voice.

Rallying the Troops

At this juncture, the two thought to gather other local HOOQ filmmakers affected by the liquidation. Haresh and Terence lead the charge on their behalf, writing emails and letters and keeping everyone—about seven affected parties in total—abreast of any updates they have.

Still, their situation differed from the other producers because, unlike them, Haresh and Terence didn’t own the IP rights to SATAILH. The contract they signed handed over ownership of the IP to HOOQ—wholesale.

Kevin*, another producer who joined the HOOQ programme a year later, tells me that he lost about S$20,000 after a part of the payment owed to him to produce a pilot has yet to be recovered.

As a fresh graduate then, he was excited to come on board to work with an up-and-coming streaming platform. With big names such as Anthony Chen and Ministry of Funny involved (and the backing of Singtel), he thought that signing a contract with HOOQ was a no-brainer.

Fortunately, the contract he signed with HOOQ was voided as there was no signature from their end. He, as well as fellow producers who joined the HOOQ Filmmakers Guild in 2020, managed to keep the IP rights to their works.

And so did Anthony Chen.

Wet Season: Hung to Dry

Chen’s relationship with HOOQ started when the streaming platform acquired the rights to distribute his 2019 film, Wet Season, starring Yeo Yann Yann and Koh Jia Ler. The film tells the story of a Singapore secondary school teacher and the relationship she nurtured with a student in her class.

“Through the acquisition, HOOQ had exclusive streaming rights to Wet Season in the whole of Southeast Asia,” the 38-year-old filmmaker tells me from the living room of his home in Hong Kong.

As part of the acquisition and investment, HOOQ had to pay Chen US$440,000. But only US$110,000 came through. Also, as part of the deal, they were equity partners and will share in revenue from the exploitation of the film on all avenues.

“My team and I were left in debt of US$330,000. That money was supposed to fund part of the production budget of the film.”

Like Haresh and Terence, Chen had to take up loans. To this day, Chen has never paid himself a salary for Wet Season. “If I could pay everything else, it’s good enough already.”

Similarly, Chen had no reason to think that HOOQ would ever get into a financial conundrum. “They just felt credible, you know?” he recalls.

“When I met the HOOQ management, I was in the Singtel office. I don’t think there’s any reason to doubt.”

So when the liquidation was announced, Chen, like many other producers in his position, was in utter disbelief.

He immediately rang up some lawyer friends to talk about options. “My friend tells me it happens a lot and that it’s very unlikely I will get my money back.”

Still, Chen secretly hoped the monies owed to him would eventually be paid back. In full.

All that changed when he went into the first liquidator’s meeting and saw all the documents that showed proof of debt. His US$330,000, according to the documents he saw, was low on the pecking order.

“It might not be a lot, but for a small outfit like mine, it is everything.”

Going In With Faith

Chen still holds on to the IP rights of Wet Season—unlike Haresh and Terence. Without IP ownership, the pair are legally bound not to screen SATAILH on any other streaming platform, including YouTube.

To be fair, they knew what they agreed to when they signed the contract. “From the time we applied, we knew the IP would not be ours to hold. So we went in with eyes open.”

“I don’t see any issue with that, fundamentally,” Terence adds, “because if you’re opening the net for anyone to pitch a TV show, which doesn’t come often, the caveat is that they own the IP.”

Traditionally, this shouldn’t be an issue if the payment comes through. Unfortunately, in this instance, it didn’t.

Despite the complications, Haresh held onto the hope that this big break would allow them to showcase what they could do and lead to other projects.

Perhaps, Bithos’ clarification in his email would make clearer the fate of SATAILH’s IP: “If there is an asset (including IP), typically that asset will be available for sale by the liquidators to any interested party for the highest bid”.

“The proceeds of which will be distributed to the creditors according to liquidation laws. That sale process will take (sic) commence only after formal liquidators are appointed. My experience thus far in HOOQ Singapore with other IP assets (e.g. the tech code base) is that this may take 1-2 months.”

“We went in with that faith,” adds Haresh. “In hindsight, it is, of course, not the best thing to do, but we weren’t in a position where we had leverage, you know?”

Soured Relationships

The other thing that took a turn for the worse was their working relationship. Terence shares that they had many tough conversations that involved contemplating leaving the industry altogether.

Haresh remembers several hour-long phone calls discussing the possibility of shutting down Ministry of Funny.

“Both of us took personal loans—that made the problem hit much, much closer to home. It was easy to blame everything on each other. I was already contemplating finding another job, but it wasn’t easy for me to tell him that. I hated those damn calls.”

Beyond one another, the relationships with their family also suffered. It was a situation exacerbated by the Circuit Breaker, when they were stuck at home.

Haresh puts it best: “You want to run away from these questions also cannot.”

“I found myself in a place where I had to justify to the family why I was pursuing my dreams despite all these things happening to me,” Terence recalls.

“I was in the midst of chasing after my dream with the possibility of a big break coming, and then this thing happened. Now, I have to field questions from family asking if I was sure this was something I wanted to do.”

For Terence, it’s almost like starting back at square one of having to justify their existence and passion.

“We had to ask ourselves again: Why are we even doing this?”

Three Years of Nothing

It’s been three years since the liquidation. The liquidation end date has been delayed five times, meaning Haresh and Terence are far from getting the necessary closure. Across the three years, they never had any concrete confirmation from their former HOOQ bosses if their S$205,114 would ever be recovered.

Bithos seems to have put the incident behind him—his LinkedIn description of HOOQ states that it was ultimately sold to Coupang, Korea’s largest e-commerce company.

“It is reasonable for any creditor not to expect payment of any money owed,” he wrote in his email to Haresh and Terence.

When contacted by RICE, the former HOOQ CEO was unavailable to comment by the time of publishing.

“It’s so easy for everyone to absolve themselves of any responsibility,” Haresh grimly intones after showing me the email.

“A company can decide to liquidate at any time, and suddenly all their commitments and contracts signed—all that doesn’t matter anymore. It’s just so dirty.”

To the point of contracts signed, Terence sees it as an unwavering commitment between two parties. “Even if you pay us late, we can talk it through. Pay me in tranches, whatever. But just pay me.”

As the years went by with nothing concrete to go on with, they started to wonder if it was time to move on. The back-and-forth process for answers and accountability was wearing them down.

“Every few months, whoever we were in contact with [at HOOQ and Singtel] would tender, and then we would get passed on to someone else, and then we had to restart,” Haresh says.

It was also hard for the pair to continue rallying the other producers who, by now, were more than willing to put this whole incident behind them and move on. Especially when all they got at every juncture was a roadblock.

Compassion from the people they used to work for never came. For Haresh, all he wanted was for them to express empathy. “But all we got was an indication that it might be best to move on.”

To date, Haresh and Terence are technically bound to the terms they’ve signed. There has been no confirmation that they could buy back their IP.

“We’ve honoured the liquidation process as far as possible. We haven’t said anything publicly about it until today,” Haresh affirms.

But after three years, the pair decided that enough was enough. They’re ready to show the world the work they’ve produced.

“Everyone put their heart and soul into this project. We don’t even want to monetise it—we just want people to be able to watch it,” Haresh declares.

Closure on Their Terms

On 27 March 2023, Haresh and Terence released the first two episodes of She’s a Terrorist and I Love Her on their Ministry of Funny YouTube channel. The other six episodes are set to go live in subsequent weeks.

It is the closure that Haresh and Terence need. But it is, by no means, an indication that all is forgiven.

“I’m still pissed off about it,” Terence tells me. “So many creative people got screwed over during this process.”

For Chen, the messy affair opened his eyes to the harsh, cruel, and unrelenting realities of the media industry. “As a filmmaker, I’m, accustomed to being hopeful,” Chen says. “But after this incident, I don’t think the corporate world has any room for empathy or sympathy. It’s designed to protect the stakeholders.”

Nothing is too big to fail, as Chen learned—not even when they’re backed by Hollywood studios and the biggest telco in Singapore.

Finding a Way To Survive

As we approach the close of our interview, I wanted to know why Haresh and Terence decided to speak to me, given the legal repercussions they may face.

“We want to close this our way,” Haresh offers. “But even as we move on from this, I never want to lose this anger. Because if I lose this anger, I don’t know if I can find the motivation to entertain the possibility of getting this out there into the world.”

Terence hopes telling this story can help people in similar positions. “Maybe we can help anyone else who has gone through the same thing to know that, okay, there are people who have gone through this.”

“We have all these platforms to use to tell our story. If it helps someone going through what we’ve been through feel more in control of their situation, that is good enough for us,” Haresh adds.

“It’s about finding a way to survive.”