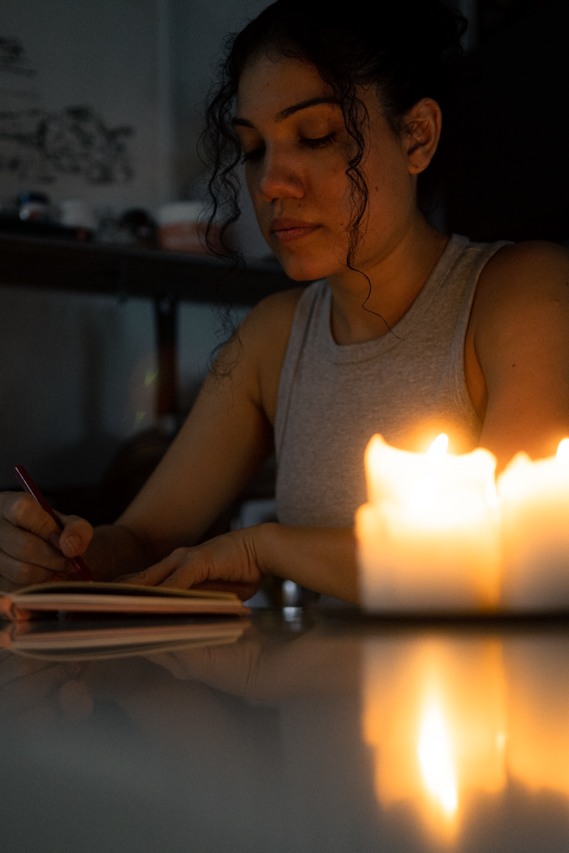

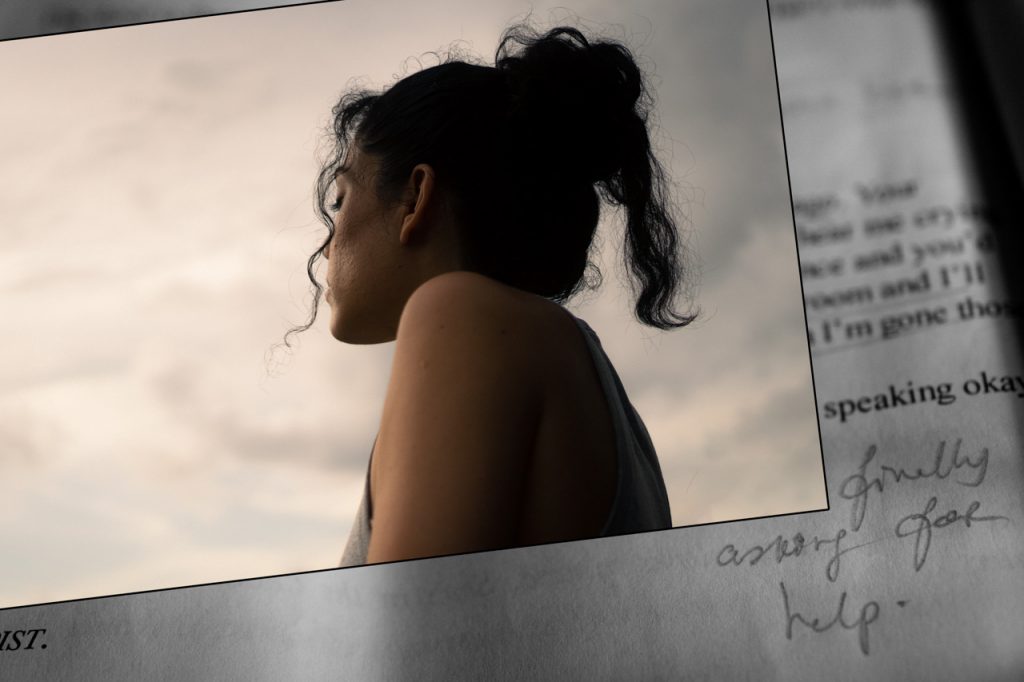

All photos by Stephanie Lee for RICE Media.

I once likened going to work to cosplaying as a functioning adult. We all dress the role, speak the part and act as perfectly competent, capable and congenial humans. Shakespeare said it before, didn’t he? Something about the world’s a stage, and everyone’s an actor.

Acting is like a sales pitch. I try to convince you that what you, as the audience, see and feel is real. If convincing enough, you buy into the performance—especially of me in the role of a normal, respectable human being.

Professional acting in theatre takes that to the extreme. That is to say, there’s an extensive effort to get the audience to suspend their belief truly. Hopping about while wearing bunny ears and speaking lines might work in a child’s play about The Tortoise and The Hare, but no one’s really received awards for that.

As actors, the most challenging part about acting isn’t just remembering lines. It’s creating and embodying another person, and their mannerisms, in a manner that’s so convincingly real, it’s enough to inspire fervour and, for one, fanfiction. Just look at the Eames/Arthur (Inception) tag on AO3.

But what happens when fiction isn’t too far from the facts? The job also gets difficult when the person to be portrayed isn’t your average protagonist with a set of ideals and values. Instead, a tragic and complex—sometimes unsympathetic—character everyone is far too familiar with.

Introducing, Emma

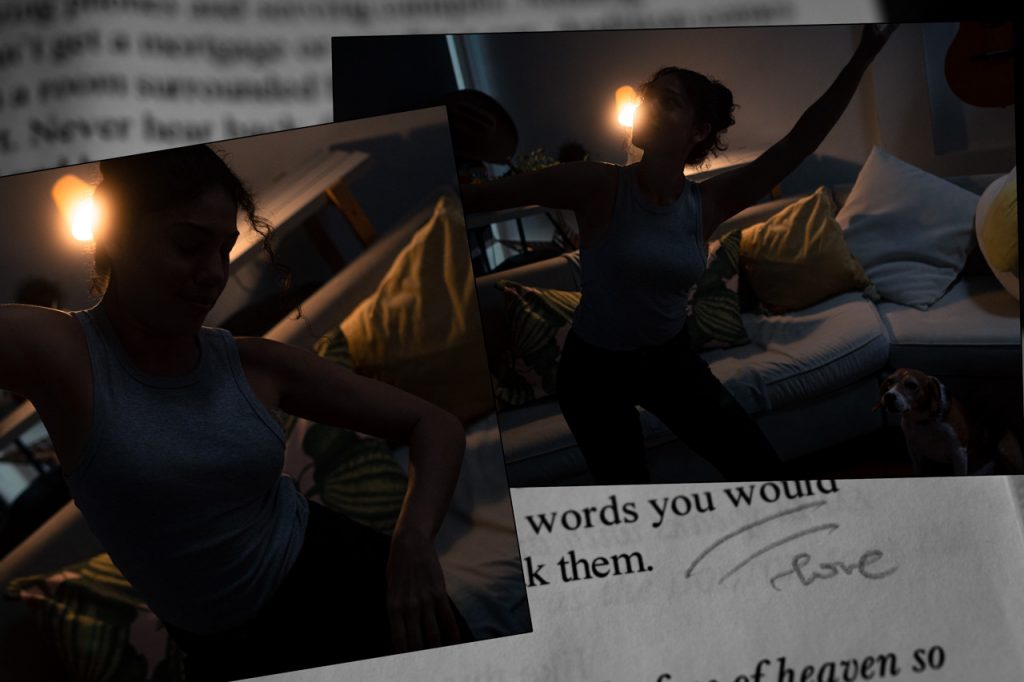

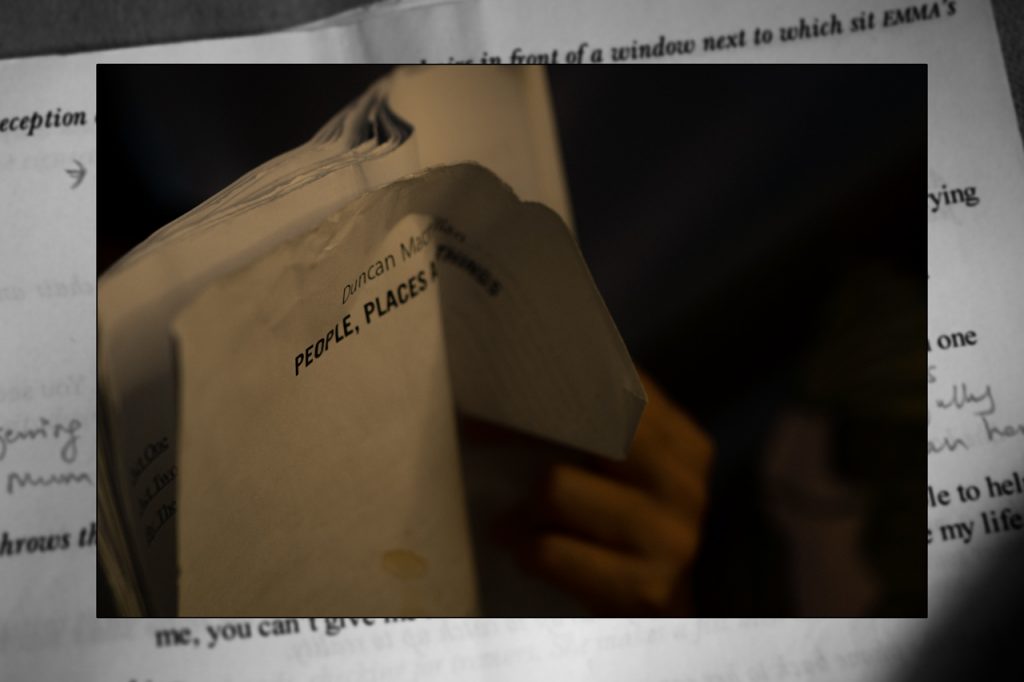

In Pangdemonium’s latest production, People, Places & Things, Sharda Harrison plays the role of Emma, an actress who checks herself into rehab for her addiction to drugs and alcohol in an attempt to turn her life around.

The play shows Emma at her lowest, ugliest and most vulnerable state she’s ever been, to the point where it’s almost disconcerting for the audience to watch.

It should have been easy for Sharda to accept Pangdemonium’s offer, but reading the script made her waver.

Emma isn’t just a two-dimensional character waiting to be portrayed with dramatic aplomb. Emma is a familiar human portrait, a train wreck riddled with struggles and turmoil, trying to free herself from the shackles of addiction.

And in Emma’s struggle to get clean and sober, Sharda saw the shadow of her former partner and his battle with alcohol dependence.

The parts of Emma seen as ‘unattractive’ are the parts of the people Sharda loves, and has loved.

Duncan Macmillian, the playwright, once mentioned in an interview that stereotypes about people with addiction revolve around “tragic people who can only die to serve the narrative.” So, when it came to writing about Emma and the cast of ensembles, he wanted to accurately and respectfully represent the daily struggle and the work that goes into recovery.

“When I did read the script I initially hesitated. I might still be hesitating. It’s not an easy task.” Sharda admits.

“I couldn’t trust myself with the material.”

Unlike Denise Gough, the actress who played Emma in the original 2015 London production, Sharda had not personally lived through the experience of drug or alcohol addiction. Could she, then, do justice to the real people who are just like Emma?

Close, Closer to Home

In 2020, Sharda had front-row seats to her former partner’s detoxification process.

As a result of the Covid lockdown, the pair were internationally separated for eight months, during which her ex’s drinking habit took a turn for the worse. Hidden outside the frame of his frequent video calls were countless bottles of booze, downed like water to drown his pandemic-related frustrations.

Eventually, he suffered from a stroke, due to seizures from all the toxins in his body. When his friends rushed them to the hospital, Sharda was informed her partner only had a 50 per cent chance of survival. All this while, she was stuck in Singapore, stuck at work, completely at a loss.

When she made it across the sea, what greeted her was just a shell of the person she used to know. The next four months were spent accompanying him through rehabilitation, finding an in-house nurse to handle the medical procedures. She also found him psychological help from Alcohol Anonymous (AA).

She watched as he slipped in and out of a stupor, the way he almost seemed “hypnotised, delusional even.” His hands shook uncontrollably from the withdrawal. She saw him at his most vulnerable—took care of his most basic needs, and dealt with his unstable temperament. All this while, Sharda could still see the person who loved her with all his heart inside him, fighting to recover and to return to her whole again.

Sharda watched him fight to live, and win, every day, knowing fully well that death only had to win once. And through it all, she made the choice to hold his hand.

There were those who disagreed with her decision simply because her then-partner was, in layman’s terms, an addict. Sharda knew better, that her partner was a ‘person with addiction’, a person who had to turn to something to deal with his trauma and, in turn, fell victim to dependence.

“Addiction is a disease, I stand by it.”

Now given the opportunity to represent it, Sharda acknowledges that the weight of treating Emma’s portrayal with the sensitivity it needs is hers to bear. Not just for her ex, but for others like Emma.

Representation, Presentation

Representation, or specifically nuanced portrayal, is finicky business.

As an actress, Sharda is well aware of the kind of power she wields when it comes to influencing people’s perceptions. She finds it scary how out there, there’s a real person who’s just like the fictional character she plays. Even more so, how an actor’s treatment of a character affects the way society looks at the people said character represents.

Let’s not even talk about the harmful effect films like Split or Flight have on people with dissociative identity disorders or people with an addiction to alcohol.

The thing both movies have in common is the simplistic approach to the portrayal of their characters. There was an active choice to be presentational instead of representational. To just paint broad strokes and play the stereotypical, archetypal characteristics.

The audience knows stereotypes. When they watch a performance, they’re looking for the stereotypical behaviours to cement what they presume of the character. The challenge here, Sharda says, is giving complexity to the character. Perhaps, then, the audience will realise the character is just as much a multifaceted human as they are.

As the artistic director of Folding Chair Classical Theatre, Marcus Geduld, puts it: “An actor’s job is to know the breadth of human possibility and the depths of his or her own possibilities. He or she must pull from this well and surprise us. Otherwise, the actor becomes boring and predictable.”

There’s no ‘easy’ way to be a good actor, because that’s just a “massive simplification of the complexity of just being a human fucking person”, to quote People, Places & Things. Every character is complex, and every character has layers, and that’s what makes them human. And in effect, convincing.

By giving a nuanced treatment to sensitive roles like Emma, it doesn’t just lend authenticity to the performance. It also allows the audience a greater emotional understanding of the people just like the character.

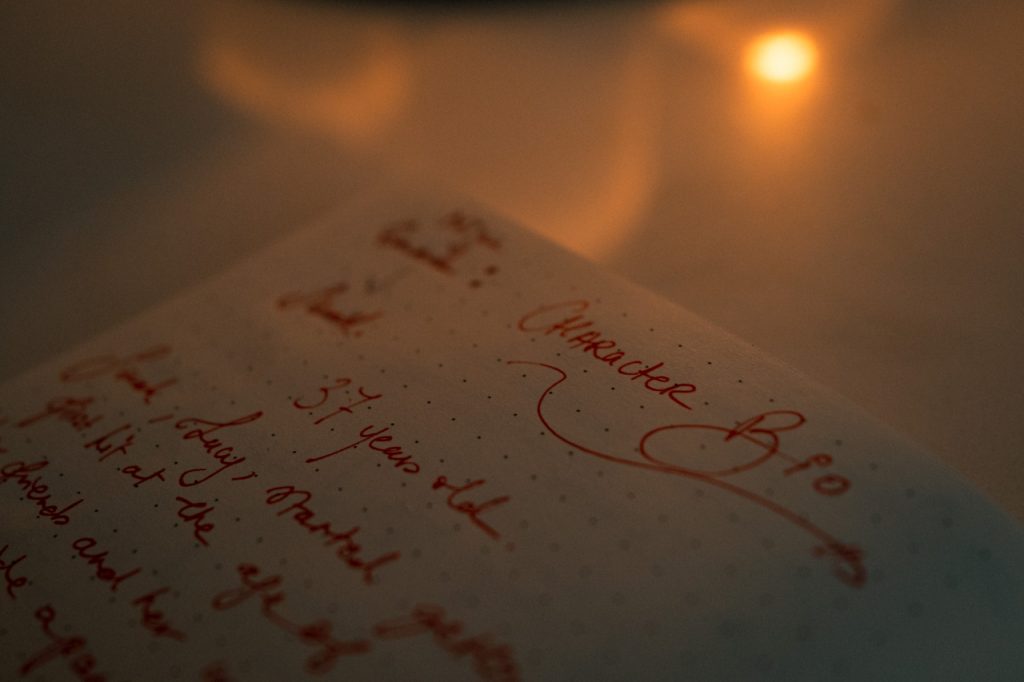

Compartmentalising Inspirations

Sharda’s experience with substance addiction is second-hand at best. It’s normal—there are some things that actors are fortunate enough to not have experienced, and will never truly understand.

And so, she speaks with people similar to her characters to find a point of connection. For Emma, she learnt that people who had been addicted to drugs weren’t addicted to the substance itself, but rather the feelings of being loved and the escapism drugs granted them.

That type of addiction, Sharda is personally acquainted with. Once addicted to playing roles on stage and the validation she received while performing on stage, she too had gone through withdrawal when forced to return to ‘reality’ offstage.

Along with her previous partner’s history, Sharda files away and compartmentalises the different experiences to create what’s essentially Emma’s databank. It’s prep work for the job, but it also helps her to process the past in a healthy way.

At the start of the production for People, Places & Things, Sharda hadn’t been sure if she could relive the entire rehab journey she had just gone through with her ex. Now, she’s able to tap into the memories that allow her body to feel and thus portray all of what makes Emma Emma within a two-hour performance.

What’s left is a (pseudo) shamanistic process—the act of letting go of Sharda, and embodying Emma on stage.

And, Scene

Pangdemonium’s page describes Emma as a professional actor, consummate performer and a chameleon-like make-believer. She’s also described as a pathological pretender, a compulsive liar and a hopeless addict.

Sharda hopes the audience sees none of that.

“I want the audience watching to see a conversation between normal people, not an addict and a doctor, or an addict and caretakers. Because at the end of the day, Emma is just human.”

The production’s run will eventually end and the curtains will fall on Sharda as an actor. But Emma’s story will continue in the lives of the people just like her.