All photos by Stephanie Lee for RICE Media.

Watching a bunch of men stick decals on a window pane wasn’t exactly my idea of how to spend an early Monday morning. Judging by the way my colleague, Stephanie, listlessly sipped on her teh siew dai, it wasn’t hers either.

Still, there’s a sense of anticipation in the air as the crowd of journalists around us mingle around the fourth floor of City Square Mall, waiting for Singapore’s first manga library to welcome us all in. Weeb and non-weeb alike.

ADVERTISEMENT

The opening hours (10 AM to 10 PM) are stuck firmly to the window, and the National Library Board’s manga library finally opens. There’s much to be said about Singapore’s first specialised and unmanned library, but all that took a backseat the moment I picked a comic off the shelf.

Gods, I can’t remember when was the last time I cracked open a physical copy of a manga. Maybe it was 15 years ago—the first and only time my parents had been willing to buy a (relatively) expensive book that I devoured in half an hour.

It was just the first volume of Naruto in English, but I remember it as the time when my reading chakra went to the next level. Dattebayo.

Accessing the Inaccessible

The smell of a fresh physical volume sent me into my own Ratatouille moment. Had it not been for Stephanie’s prodding, I might have abandoned work and turned myself into a permanent fixture at the library.

It’s a reasonable reaction, I think. For most enthusiasts in Singapore, being able to read a physical volume is a luxury and a privilege in itself. That first and only English manga I got cost a hefty $16 back in 2009, more than twice the price of its Chinese counterpart. I would argue that English manga in Singapore was, and is, still more of a collector’s item than it is an actual reading material.

After all, each volume only holds an average of five to seven chapters. A single book isn’t as much binge-reading material as a regular novel. If you plan on reading only physical manga, purchasing the entire series is pretty much a given.

Reading pirated scanlations (a portmanteau of scans and translations) has long been the solution to bypassing the financial and language barriers, though it’s not one that manga enthusiasts are proud to admit. It’s a more dignified alternative than begging that one rich classmate who owned the entire collection of Fruits Basket to loan you a copy in exchange for your lunch money, at least.

ADVERTISEMENT

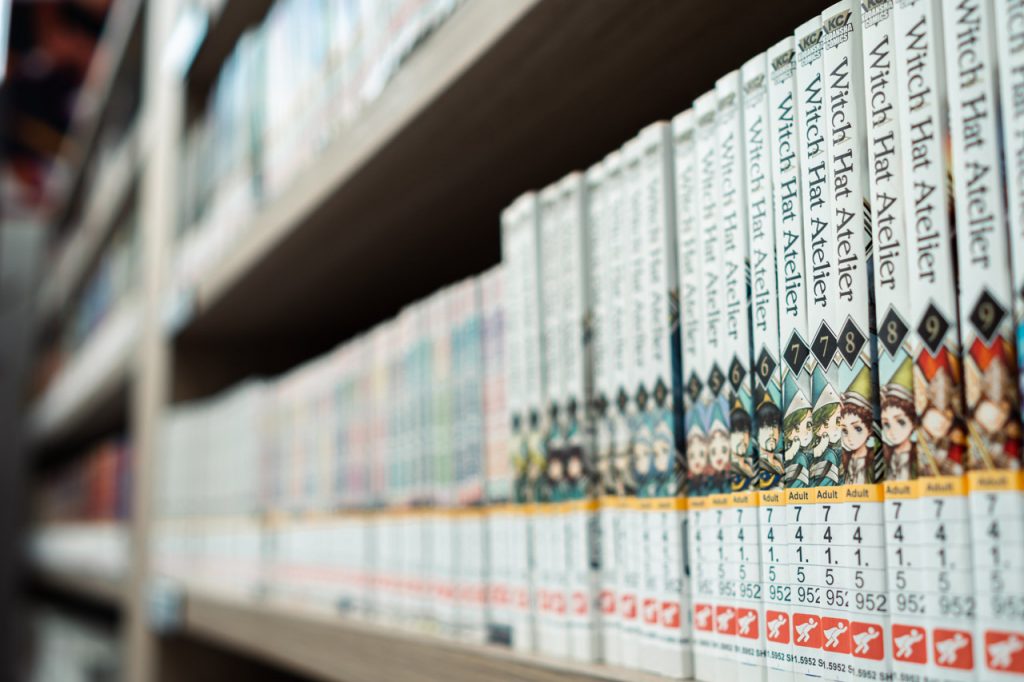

Yet, here within this liminal space between Daiso and Astons, there’s a collection of 5,000 comics that are just…free.

Yes, I know I’m describing the very concept of libraries. But for a community whose typical access to a physical manga is by appreciating it with plastic wrapping, it feels bloody surreal. Especially since this library involves patrons scanning their identification cards to enter the space, pick the book(s) they want and check them out by walking out the way they came in.

Restarting the Bookworm Club

Standing in front of the various publications gathered is the man behind the pop-up manga library concept: Johnny Lau. Despite his decades of titles, most notably as the creator of Mr Kiasu, he remains rather reserved in his responses to the interviews. Almost sheepishly so.

For the 52-year-old, the manga library came about as a desire to just get Singaporeans to fall in love with reading again. Plain and simple.

“[This library] is a topic of interest for some reason,” he tells me after, seemingly befuddled by the press attention.

Depending on your news feed, Singaporeans are either reading more or reading less books these days. Article headlines, on the other hand, they read plenty; article itself be damned.

What I do know for certain, though, is that I’ve yet to come across a demographic in Singapore that reads as voraciously as otakus. There’s always some kind of hyperfixation, usually multiple, within the community—whether it’s a new favourite like Bocchi the Rock! or a classic like Hunter x Hunter (please pronounce it as “Hunter Hunter”).

Personally, I hardly go a day without reading some sort of manga or manga-adjacent material. Perhaps Johnny’s onto something by choosing manga as an introductory medium to inculcate reading habits.

Winston Tan, Head of Planning and Development at the NLB, concurs—having visuals to supplement the reading experience makes it less daunting to kids. Long past are the days when reading snobs believe in “higher literature” anyways. In the RICE office at least, it’s perfectly normal to discuss the allegories present in Beastars alongside the story-shaping lessons gleaned from John Green’s The Anthropocene Reviewed.

As long as Singaporeans are getting into the habit of reading—whether it’s The Adventures of Moby Dick or Campfire Cooking in Another World with My Absurd Skill—that’s good enough already.

Not Your Usual Library

If you need recommendations, Johnny suggests Komi Can’t Communicate, a story about a schoolgirl with a severe communication disorder and her classmates’ endeavours to help her make friends. The concept of having a main character that doesn’t speak heavily appeals to him as a writer.

But if that’s not your cup of tea, you could always ask the robot out front.

More specifically, the Mr Kiasu robot that’s sitting in his booth by the entrance. It’s developed by local social robotics company Dex-Lab and programmed with an AI-generated voice that actually speaks Singlish. Behind his box is an illustration of his yassification.

Apart from explaining how the library works, Mr Kiasu (the robot) is also capable of offering recommendations based on your interests. It does away with the whole paiseh experience of revealing what kind of preferences you might have too if you’re one with gap moe—when your interests contradict the impression people have of you.

Finding the recommended volume itself is also pretty easy since NLB has opted to arrange the books according to the title instead of the authors. What’s also amusing is finding Johnny’s SupeRich next to Spy x Family (like Hunter x Hunter, the ‘x’ is silent), and The LKY Story next to The Legend of Zelda.

In a regular library, Singaporean comics and Japanese manga might never be found on the same shelf. Here, there’s an opportunity for curious readers to give some local works a try.

It’s just a pity that the majority of local comics can’t be loaned out. Understandably so since they’re on permanent display, donations from prized personal collections.

Changing Watercooler Topics

With legal streaming services like Netflix and Disney+ making anime more mainstream nowadays, it’s nice to see the barrier to entry to manga come down too. If you told me 10 years ago that I’d have colleagues arguing about Chainsaw Man or Attack on Titan over lunch, I’d never believe you. And yet, here we are.

Alas, the manga library will only be around for six months. Johnny still holds onto the hope that he can one day turn this concept into a manga cafe of sorts. Or at the very least, add seating areas to the current drive-through Grab-n-Go concept so visitors can experience the beauty of binge-reading manga while surrounded by books.

For a nation of weebs, will a manga library fire up a love for reading? It just might, according to my Editor-in-Chief, whose childhood reading diet consisted of Bookworm Gang, Doraemon, and Kiasu Krossover comics alongside Roald Dahl classics.

“There’s no escaping the fact that comics and manga suck you in fast. Before you know it, you realise that you’re actually fine with sitting down with a book and absorbing the craft of telling stories.”