All images by the author

Some names* have been changed

“How much money do you earn each month?”

This is the first question a Vietnamese woman asks Marcus* in his hotel lobby, during an event organised by his matchmaking agency. He has flown in from Singapore just the night before, and this is the first meetup in a week-long endeavour.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Also, can you buy me Louis Vuitton bags?” the woman continues.

Ready to move on, Marcus looks to the next table where six women sit, each one eagerly waiting to meet him.

“Ok, thank you for your time,” he chirps to ‘Louis Vuitton lady’ before signalling for the next woman to come over. He goes through about 20 women before deciding to call it a night. The next day, he does it all over again, rinse and repeat until he finds a suitable companion.

Marcus tells me that this is all part of the process of finding a wife through a matchmaking agency. “For S$10,000, they organise a week-long trip for you in Vietnam and almost guarantee you can come back to Singapore with a bride,” he explains.

“It’s very well organised because you get to meet many women, but, you know, some don’t speak English, some are very young—like 18 or 21,” Marcus mumbles. “And after every encounter with each woman, her agent would come up to me and ask me if I wanted to marry her or not.”

“I didn’t want to say yes or no in front of her, but they would insist, asking me what my heart desired.”

In his late thirties, Marcus, a tech professional, would leave Vietnam without finding a wife. While the trip was enjoyable, and most potential brides were friendly, he didn’t feel emotionally and mentally equipped to make a lifelong commitment of that nature in such a brief period of time.

“It felt strange having to decide whether I wanted to marry someone after just meeting them,” he explains. “After just one coffee, some of them would ask me: “So, are you going to marry me?”

The matchmakers

All my visits to True Love Vietnam Bride Matchmaker take me back in time. The office sits on the second floor of the desolate Orchard Plaza, built in the 80s. Apart from a few tailors, beauty stores, and convenience marts, large swathes of the mall have been left unoccupied.

ADVERTISEMENT

One, however, is hard to miss—it has fluorescent lights, a bright orange exterior, and the words “FIND LOVE” plastered on its window next to photos of young Vietnamese girls.

The proprietor of this establishment is 60-year-old Mark Lin, who founded True Love Vietnam Bride Matchmaker in 2002. Originally from Taiwan, he grew up travelling to Vietnam with his father frequently, giving him ample opportunities to become acquainted with the country and its customs.

As a young adult, Mark also worked part-time for a Vietnamese bride matchmaking agency in Taiwan and eventually, when he moved to Singapore, set up his own business of the same scope here.

On top of having a disability on his leg, Mark didn’t grow up in a wealthy home. For these reasons, women were never interested in him throughout his teen and young adult years. He did, however, find an ailment quite early on: money. To this day, he says this is his only armour protecting him from the pity of others.

After a divorce, Mark is now married to his second wife, a Vietnamese woman he met while on the job. Half-joking, he openly implies that his economic status is one of the main reasons she married him.

Money is a topic that repeatedly comes up in my conversations with him. The more we discuss relationships, the more I notice how he approaches love in an efficient and practical manner. He has become so accustomed to looking at couples from the lens of a matchmaker that he often speaks about his own relationship in the same way.

At one point, my colleague Larissa asks, “What is more important, money or love?”

“Money!” he eagerly snaps. “Without money, there is no love.”

One of Mark’s first customers and now his longest-serving employee is an amputee named Roger, who he met close to 20 years ago.

“I went to his office because of my leg,” Roger, a Singaporean man in his sixties, recalls with a smile on his face. “I am an amputee, and I told Mark that I am not his usual customer. I asked him if I could find a wife—he was pretty hopeful.”

“Mark showed me a photo of a girl, and I asked him to check if she was ok with my disability. She said she was open to meeting me, which we eventually did in Vietnam,” he shares.

“After a few days of getting to know each other, I brought her to Singapore, and we got married. We have two kids now.”

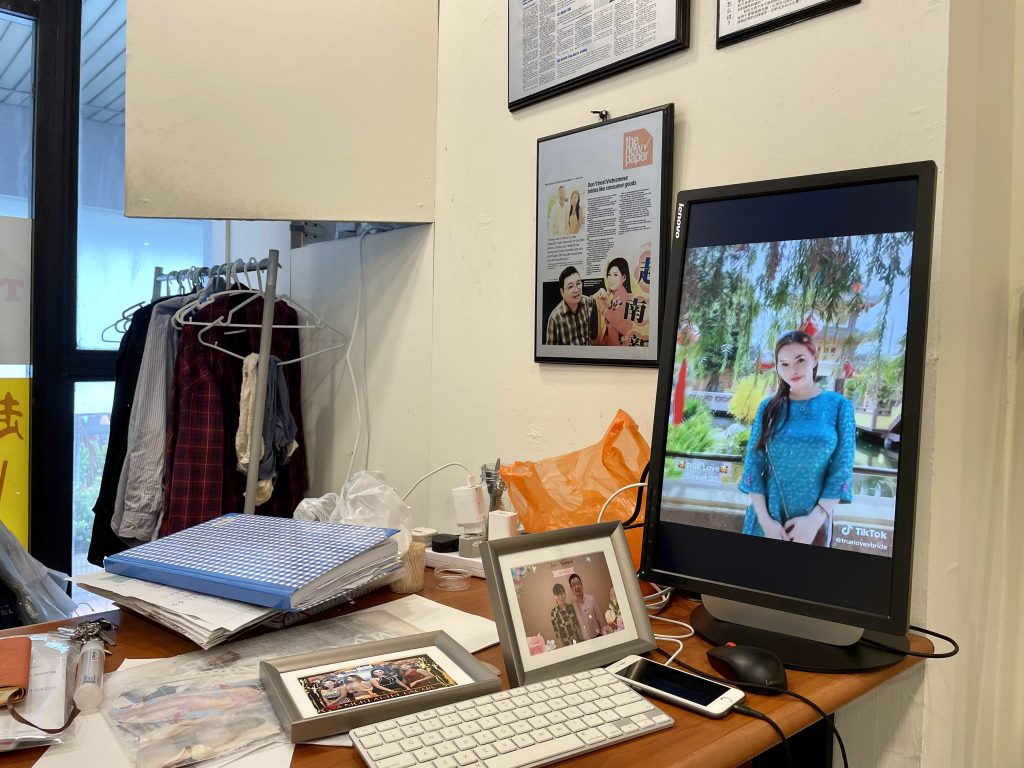

Roger is amiable, but he prefers to remain quiet and let Mark speak for him. They sit side by side at the back of their office, juggling phone enquiries, administrative paperwork, and discussing business plans.

Constantly on calls, I hear them organising trips to Vietnam and reminding clients to get their ART tests done. Every so often, a client walks into the store, many of whom are in their thirties. They usually sit before Mark quietly, whispering, trying not to reveal too much information about themselves to anyone else in the room.

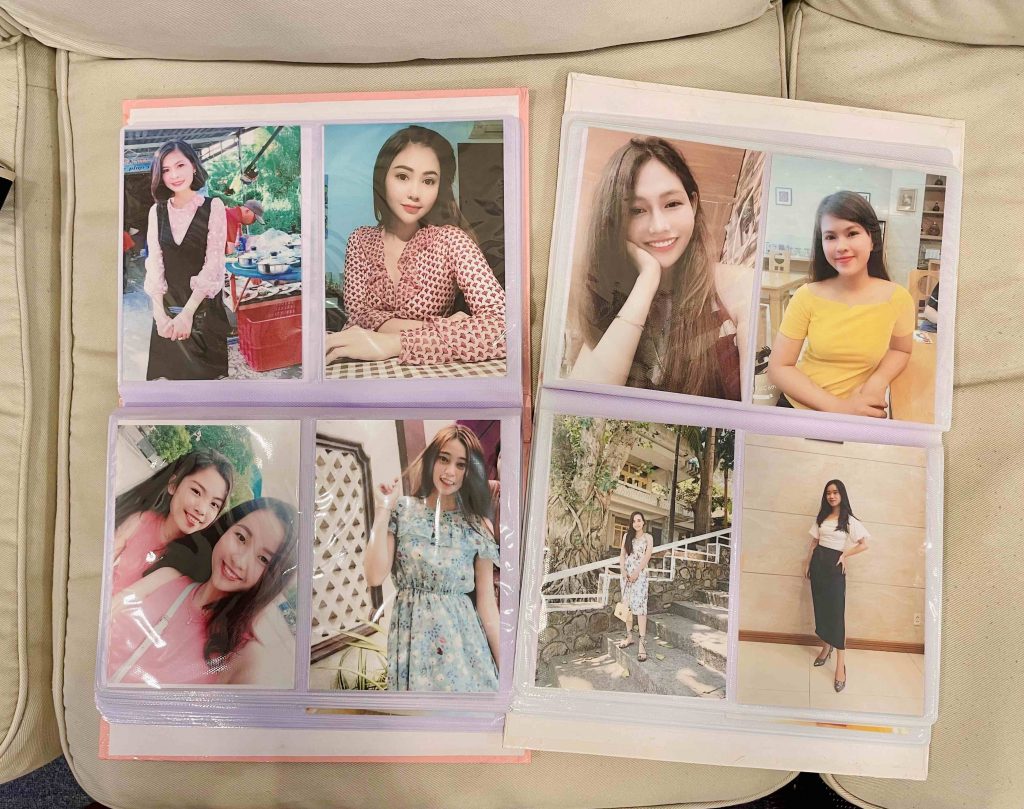

No one minute at this love headquarter is the same. At one point, I find myself sitting by Mark at his desk, between towers of files and used mugs, looking through portfolios of prospective brides. Then suddenly, his acquaintances from the shops nearby pop in to greet him, resulting in us all conversing together.

Throughout all of this, Mark never sits still. He hobbles between his desk and the chairs scattered around the office, stopping to talk in between so he doesn’t lose his train of thought.

In the background, Roger quietly goes about his work, but Mark never misses an opportunity to involve him in the conversation.

“When I grew up, my dad always did what his boss asked,” Mark says, looking over at Roger. “But when I ask Roger to do something, he never listens.”

They both break into a laugh.

Shadowbans, warnings, and virality—matchmaking in the social media age

Mark’s most recent recruit is Nas*, a younger, more energetic man who runs the agency’s social media accounts. Nas also got to know Mark from his search for a wife.

After a failed attempt to get married in Singapore during the pandemic—travel restrictions meant he could not travel to Vietnam—Nas offered to help the company with its online presence on TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook. As part of his work with the agency, he followed them to Ho Chi Minh on their last trip and met his current fiancee through a stroke of luck.

Like Roger, Nas cares deeply for Mark. I can see it in the way he helps translate his broken English or when he tries to soften the blow of his often forthright words. Still, I don’t think the two men look up to Mark because of his ability to source brides but because he gifted them with the ability to dream of a happy home when they didn’t think it was possible.

I don’t probe too much on this, however, as Nas doesn’t easily get lost in sentimental talk. Instead, he would rather talk about the most troubling aspect of his job as a social media manager: TikTok.

Sitting in front of a large vertical computer screen, he takes me through some of the videos that have gone viral on the app. Most of the clips feature Vietnamese women introducing themselves, with text stickers describing their features, reminding viewers that she is looking for a husband.

Mark will stand beside the woman and introduce her to the camera in some videos. These, Nas tells me, are the first to get banned by TikTok for “sexual content”.

So far, their account has gotten taken down four times. For a company so reliant on their online exposure for sales, the impact of this compounds each time.

“We see a dip in customers when our account is down,” Nas explains. “At the start, when our TikTok account was doing really well, we saw a surge in interest in our business. Up to 95% of our customers told us they found us on TikTok, so you can imagine how it hurts us when our account gets banned.”

Nas has tried appealing the notices and asking for the app to help them understand what they are doing wrong, “but they never tell us why exactly our content is being banned,” he shares.

“We even tried showing up at the TikTok office, but we were turned away because we had no appointment. And online, there is no way to make one.”

In this new digital age, small businesses are increasingly dependent on social media for marketing and branding purposes. This begs the question, how much power do the tech giants hold over them?

And when these apps have the ability to wipe out a company’s account with little to no explanation, what options are the businesses left with but starting again from scratch?

In the past years, TikTok has come under fire for promoting harmful content to young individuals—just recently, a 10-year-old died after reportedly taking part in a ‘choking’ challenge she saw on the app.

In response, the app regularly updates its policies to better “promote safety, security, and well-being.” As a result, its algorithm becomes increasingly unforgiving, removing any content it deems to promote sexual activity, harassment, bullying and hateful behaviour.

The realities of a transactional marriage

While their online content gets repeatedly banned for being inappropriate, the reality is that the day-to-day functions of the agency are pretty ordinary.

Clients and potential brides have complete autonomy over their arrangements, meaning the agency simply acts as a means of introduction—strictly no raunchy business.

Furthermore, the concept of matchmaking is nothing new nor contentious.

In Singapore, the Ministry of Family and Social Development has accredited a list of dating companies. The government also established the Social Development Unit (SDU) in 1984, now called the Social Development Network, to organise events to help singles meet potential partners.

Recent years have also seen the resurgence of dating companies marketed to younger individuals, such as Kopi Date. Their trendy and aesthetic website declares that they are “not a dating app” and “not a matchmaking service,” but instead on a pursuit of “humanising 1:1 connections.”

Evidently, younger demographics have gotten no better at finding partners on their own.

But unlike more contemporary dating companies, Mark’s agency is shamelessly old school and takes a no-frills approach to matchmaking. And while he technically sells the idea of love to his customers, it would be naive to assume that it is what they get.

Marcus tells me that a large portion of the women he met in Ho Chi Minh had come from small towns over eight hours away by bus. These villages often don’t have electricity and are ridden by poverty. Hungry for better circumstances, these girls are not picky about who they marry as long as they get the opportunity to travel abroad and into a more comfortable life.

Mark’s clients are happy to give their prospective brides this opportunity because, in exchange, they get to settle down, gain a life partner, and have children when this may not have been possible for them before.

Such is the case of both Roger and Mark, who are disabled and had struggled for years to find a woman who would accept them with their condition.

“It is hard to find someone to settle down with in Singapore at my age,” Nas confessed.

At first, I found this hard to believe—Nas is well-groomed, presents himself well, and has a full-time job (outside of his work with the agency) in a well-established company.

But the dating scene in Singapore is so dire, he continues, that even much younger guys are struggling.

The downside of matchmaking

He gives me the example of a guy in his early twenties who came to Mark for help just a few weeks ago. Nas questioned the boy’s true intentions when he showed up at the office because he was “good-looking” and an “artist.”

The boy’s reasoning was simple. He was so set on getting married and having children that he believed a matchmaker would be more efficient than waiting to meet someone in person or on a dating app, where the process can take months, if not years.

To some, this is unthinkable. Pop culture has taught us that dating should be a complicated, slow process in which two strangers gradually unpeel the layers of each other’s psyches. But for many, this is too bothersome.

Turning to a matchmaker may be a more straightforward solution, especially when dating becomes a harrowing ordeal. But there is an undeniable compromise that comes with it. To find a life partner in a tight timeframe, one must trade off the opportunity to meet someone they can get to know slowly, and with whom they can build a deeper connection with first.

Still, not really knowing who you are walking down the aisle with has its risks, especially for the brides, who presumably want to avoid finding someone simply after sex.

In 2012, a 52-year-old Singaporean delivery driver married a 23-year-old Vietnamese woman he met at Mark’s agency. After living with her for a week and sleeping with her, he sent her back to Vietnam and asked the agency for a refund. The reason given by him was that she was too ugly.

Mark tries to deter this from happening again by talking to each of his customers and filtering out those who are not serious about marriage. Nas also says that clients “come here with one intention—to find a wife and get married.”

Marcus tells me that some agents in Vietnam tell men which girls are virgins. When I ask him why this information is disclosed, he tells me that some men have a “criteria.”

Quitting the program

After a few days in Ho Chi Minh, Marcus realised that matchmaking would not work for him.

“But would I recommend the service to someone else? 100%,” he says confidently.

“Many of the guys on the trip told me that their families were pressuring them to get a wife and have kids. I think it was a very efficient way to go about it in their case. But if you are like me and want to get to know the person for a long time first, this is probably not for you.”

Marcus went on to tell me about his last relationship, which ended just a few months ago. He had hoped she would be the one he would marry and have children with, so when it didn’t work out, he felt rushed to find someone else before he turned 40.

In hindsight, he realises that he was so stressed about his personal milestones that he didn’t give himself time to heal after the previous relationship. This would explain why he turned to a matchmaker. On top of being extremely friendly, Marcus is well-groomed and has a high-paying job in a global MNC.

The week in Ho Chi Minh was a huge wake-up call for him. For the first time in years, he was forced to stop, breathe, and think about what he wanted from his life.

“I came back from my week in Ho Chi Minh a changed person,” he shares. “Putting myself in a completely different situation was an opportunity to rediscover myself. I realised I don’t need to rush to settle down and that everyone needs to live at their own pace.”

“It’s so weird to say it, but what was supposed to be a weeklong adventure to find a wife turned into a realisation that I can be happy alone.”