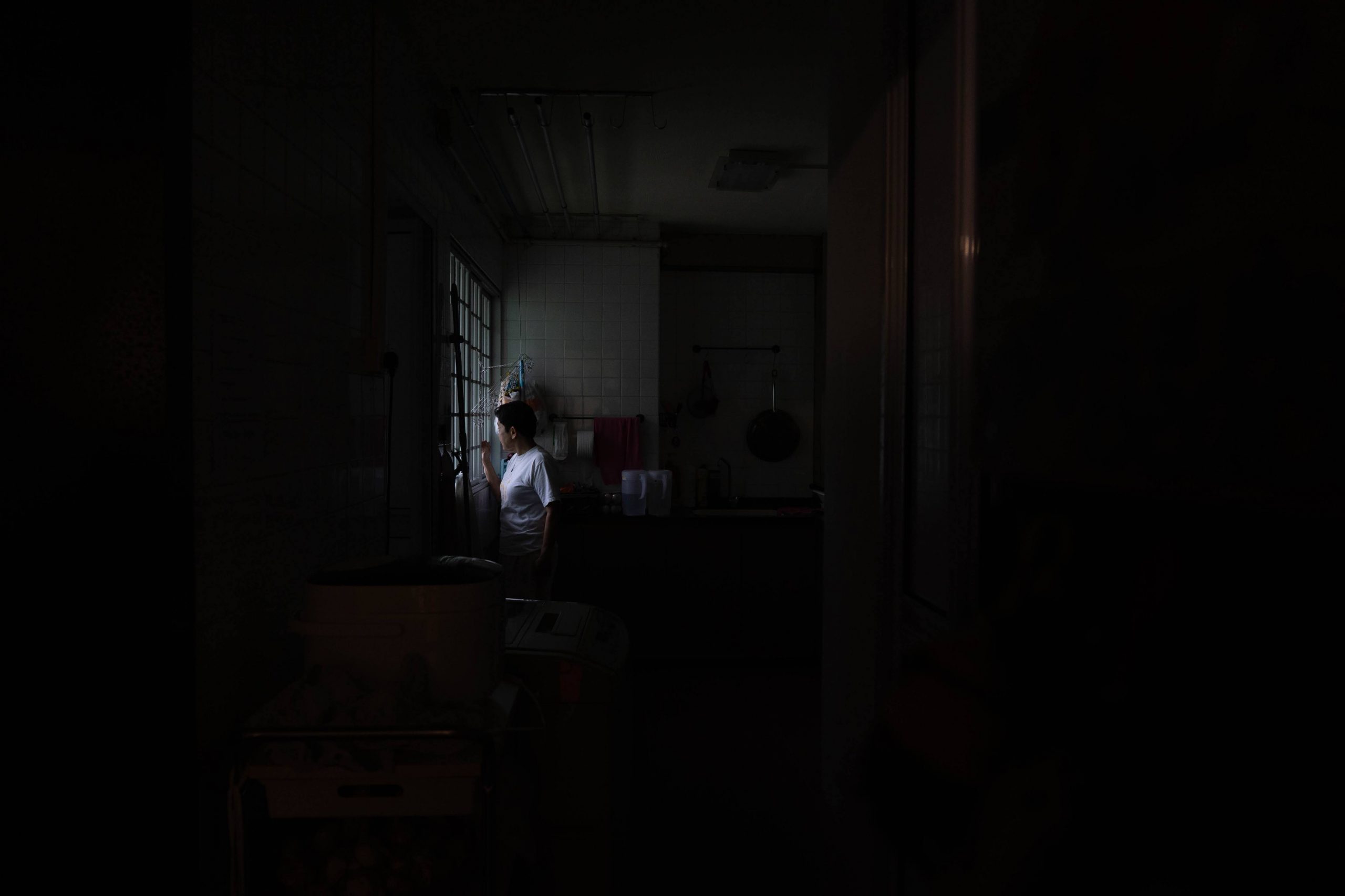

Top image: Zachary Tang/RICE File Photo

When we think about dysfunctional families, rarely do we think that mothers could be the source of familial distress. And why would we? Mainstream narratives place mothers on a pedestal. They are benevolent people who are kind, nurturing, and patient. Against all odds, they dig deep and sacrifice to raise their kids.

Sky-high expectations aside, the trouble with this traditional, one-track narrative is we tend to gloss over the ugly reality that not all mothers are equal. Some abandon their children. Some are abusive, while others are emotionally unavailable. In short, mothers too can be toxic. And they come in all shapes and forms.

Elena: “You’re just like your sister”

Elena was nine when she watched her mother kick her 16-year-old sister out of the house. Too young to fully understand what was going on, Elena stood on her mother’s side. She believed the fallout happened because her sister had vastly differing views. Maybe it would be better if her sister left, she thought.

Looking back now, as a 29-year-old freelancer, Elena realised how messed up her mother truly was. “Kicking out your daughter. Making your kids hate their siblings. What kind of mother does that?” she recounts.

She wasn’t always like this, though. When Elena was “zero to nine”, things were typical—great, even. Her mother had spoiled Elena and her two siblings with love, overseas trips, and magical activities like ice skating.

Then her parents’ divorce happened. And soon after Elena’s father left, she noticed a gradual shift in her mother’s behaviour. The most disturbing is a growing bitterness toward her eldest sister.

“She always told her, ‘You’re just like your father’ in the most disgusting tone… Then finally, she told her [sister] to get out—just like she did to my dad.”

As Elena grew older, things didn’t improve; her mother became increasingly erratic. For a time, she used nothing but water and vinegar to clean the floor, leaving the house with a rancid smell that lingered for days. She also stocked the fridge with rice and fresh vegetables—not for the humans in the house to eat but for the family dogs.

“She would tell my older brother and me, “You settle your own food, okay? The stuff in the fridge is for the dogs.” Elena was 17 then.

Never mind that dogs aren’t vegetarians. Elena’s attempts to converse or reason with her mother were either shut down or drowned out by shouting. Home became hell, and throughout Elena’s teenage years, she resorted to living in her room to escape the madness.

When Elena hit 20 and just began her career, her mother invited her to dinner. The sweet gesture turned out to be a front for a live-firing session. Livid over Elena’s lack of financial contributions to the household, her mother raged, scolded, and belittled Elena’s insecurities about adulthood. She didn’t stop even as Elena cried in full view of restaurant-goers.

The conversation ended with a threat to kick her out.

“I’m always scared I won’t have a roof over my head one day because I didn’t know when my mom was gonna kick me out,” she shares. “It’s not healthy living like that. So after that dinner, I decided to move out—I told her a few days later. We fought, and she said, ‘You’re just like your sister.'”

Upon hearing those words, it dawned on Elena that her mother would never change. Angry and upset, she moved out. Despite not talking for years, Elena shares that she hasn’t completely cut off all ties.

Every month, she deposits money into her mother’s CPF account, knowing it’ll help when the time comes. It is her final act of love—honouring the mother of her childhood.

“I don’t love her now. But she did raise me, so this is my way of showing love to the mom I had as a kid.”

SJ: The mother who can’t say sorry

Young children often perceive their mothers as all-knowing ‘gods’ who shoulder the heavy burden of child-bearing and child-rearing. This illusion falls apart as we grow older. We start to see that our mothers are not perfect beings; they make mistakes too.

The issue, however, is when they don’t apologise. This was something Shi Jie (SJ) realised at the tender age of six.

“I asked her to wake me up for something. She forgot, and it’s a normal, natural human thing to forget sometimes,” SJ recalls. “But as a child, I was devastated. A simple apology would have sufficed, but she was more interested in pacifying me than apologising.”

Thus began SJ’s tumultuous relationship with his controlling mother. Hailing from a third-world country, she had obscenely high expectations of SJ, now 28, pushing him to study hard so he could pursue the medical field as she did.

In her eyes, academic excellence was the Holy Grail.

“There was a general vibe of never being good enough. Your interests aren’t being acknowledged properly. It’s a classic case of you finding something funny, but your parents turn it into a life lesson, a lecture on how they want you to live. It got to a point where I stopped wanting to share things with them.”

While most mothers would be thrilled their children are doing great at school, SJ’s remained dissatisfied.

He was one of the top scorers in his class, but she’d grill him endlessly on why he wasn’t studying when he took a break or read literature books. “It’s ironic because English was one of my weakest subjects.”

Resentment grew, and in his early teens, SJ swore never to become like her. Even when he became an accomplished fitness instructor with certified qualifications, she still treated him like an infant, belittling his choice of career.

“I did all my research, reviewed my sources, and shared them with her—a woman of science. She still dismissed it! Like, you made a claim, I dispute your claim, and then you brush it off as your offspring being insolent.”

Dealing with her antics was exhausting. So SJ coped by ignoring her completely, going as far as reversing his sleeping patterns and staying out late to get some peace. The unfortunate side effect was that he soon became hyperaware and paranoid of her presence.

“Every time she speaks, there’s a defence mechanism. Am I going to get berated? Scolded the fuck out of? Your emotional guard goes up. Your mental guard goes up. It’s not healthy,” SJ explains. “And though we stopped talking, I notice that she treats my dad like shit.”

It’s a shame, as SJ’s only saving grace was his father. From young, he stepped in and did all the cooking, cleaning, and caretaking as a mother would. But SJ’s father was also a “passive enabler”. Throughout the years, he urged his son to protect the peace by appeasing his mother. It was easier than confronting the loudest mouth in the room.

“That’s why I left. You let people scold you and shout at you like that? Where’s your dignity?”

SJ eventually cut them off and moved in with his partner. It took him months to manage his paranoia and fear that his parents would find him. But slowly, he began to heal. Surrounded by friends who listened, SJ could finally unpack his trauma and feelings of not being good enough.

“I had the space to work on my issues without any noise, without having my guard up all the time. I had space to finally talk about my parents without being gaslit or disrespected.”

Nicole: Unlearning toxic behaviours

These days, Nicole exercises restraint before she speaks. The 29-year-old coach catches any critical thoughts before they slip out, reframes her mind, and responds when she’s calm and ready.

It’s the only way to unlearn the toxic behaviours she picked up from her mother.

“I took a lot of her bad traits. Things that I don’t like about myself are largely present in her. For instance, if things are not done to my expectations, I’d get critical and upset,” Nicole said. “Not just to myself, but I’ll scold the other person, which isn’t nice because they won’t be open to resolving conflict. But that’s how my mother resolved conflicts with me.”

Even the act of apologising is difficult. Nicole laments that her parents rarely said “sorry” to her while growing up. Instead, they show it in other ways. Her father makes amends with food; her mother throws tantrums.

“When I talk to my mom about things that don’t sit right with me, she likes to throw in, ‘Oh, I’m a horrible parent. I suck. I’m better off dead. I don’t deserve to be your mom.’ Then she’ll do the whole pity party: Cry, go to her room, lock or slam the door. It never really goes or ends well.” Nicole recalls her childhood was fraught with ultimatums, guilt trips, and gaslighting.

Illnesses she came down with were routinely dismissed or downplayed by her mother. When Nicole was 10 or 11, she came down with a “borderline 40-degree fever”. Her mother insisted they meet at a bus stop 10 minutes away before heading to the nearby Polyclinic. Left with little choice, Nicole made the journey despite feeling dizzy.

In her early 20s, she came down with a urinary tract infection. She recalls lying on the bathroom floor for 30 minutes, waiting for her mother to bring painkillers. It turns out her mother forgot.

“Wow. You can see your daughter lying on the floor of the bathroom. And you’re just like, ‘Eh, my show is more important.'”

Violence was not off the cards either. Then 25, Nicole called out her mother’s favouritism towards her sibling, and all hell broke loose. Her mother “went ballistic”—screaming, yelling, and eventually scratching Nicole across her arms. They didn’t talk for a month after.

During the cold war, Nicole’s father often coaxed her to reconnect with her mother. “My dad kept expecting me to be the person to patch things up. But I think we both knew that if it weren’t me who did it, she wouldn’t do it. She would never be the one to budge.”

A tiff over a massage chair finally broke the camel’s back.

“My dad’s been eyeing one for a long time. But my mom has this sense that this is her house, this is her space. I thought it might be an issue of money. But it turns out she thought it was ugly and didn’t want it in the house unless it was in my room, which doesn’t make sense.”

Tired of sucking things up, Nicole packed her bags and left the next day. Seven months later, during Chinese New Year, she received a call from her mother—inviting her back home for a reunion dinner. Nicole was shocked.

Her mother finally budged.

Breaking the cycle

When it was time to go home for dinner, Nicole couldn’t bring herself to go. The pain was still too great, the emotions still too raw. She called her mother to politely decline, and a four-hour phone call ensued. Years of pent-up tension erupted and overflowed.

“Initially, it went very nasty. She would say, ‘Being your mom is so hard.’ Still, towards the end, she started to lighten up. She asked, ‘What the hell do you want from me? You’re so demanding as a daughter.'”

“I told her, ‘I just want you to be okay acknowledging you’ve done not-so-good things. Acknowledging that you’re not perfect as a mom. That it’s okay, and you’re sorry.’

That was when it went well. My mother stayed quiet, listened, and started to apologise for the things that weren’t so great.”

No guilt trips. Not pity parties. No full closure, but there was effort. And that was enough for Nicole to slowly move back home.

While Nicole admits her current relationship with her mother is awkward at times, it’s a significant improvement compared to the one they had before. Elena and SJ, on the other hand, remain estranged from their mothers. There’s nothing left to say or salvage.

Elena sums it up with a sad smile, “It’s better if she doesn’t exist to me, and I don’t exist to her.”

Post-mortem

Growing up under toxic mothers is a painful, complex and traumatic experience that can affect one in deeply profound ways. Children may unintentionally replicate their problematic behaviours as adults. Still, a light shines at the end of the tunnel. With community support and self-awareness, it’s possible to break the cycle of dysfunction that runs in many families, lasting throughout generations.

It might also involve moving out if you have the means to.

SJ continues to live up to his word that he’ll never be like his mother. In his line of work as a fitness trainer, he practises extra care when he trains younger clients—treating them with dignity, listening to their concerns and interests, and providing balanced, constructive feedback.

“I talk to children the way I wish I were spoken to. I take children’s autonomies and boundaries more seriously because I wish that were the case with me as well. I basically give human decency and respect to children as I do to adults. They’re inexperienced, but you don’t get to mistreat them just because of that.”

Elena echoes that sentiment. Knowing that children will eventually grow up and become their own people, she aspires to be a better parent by playing different roles in their lives: a mother when growing up, a friend when an adolescent, and a mentor when an adult.

For Nicole, old habits die hard, but she’s adamant about changing and taking responsibility for her growth. From people-pleasing to being overly critical towards others and herself, she makes a conscious effort to catch and correct negative behaviours as they come.

“It’s all about being very, very aware and unlearning all these behaviours just so that people around me don’t feel the way I did growing up. If we have a family, I told my fiancé that I would be very sure that my kids don’t turn out like me when I was growing up. I want them to feel like they’re cared for. That I hear them, you know?”

In a society where filial piety is one of our core Asian values, cutting off our loved ones may be the ultimate transgression. But absence sometimes makes the heart grow fonder, and distance can do everyone good. It’s the space and time to heal, to reflect, or accept that your mother was not the one you deserved and isn’t worth celebrating. The bitter truth is some mothers are simply toxic. But that’s on them—not you.