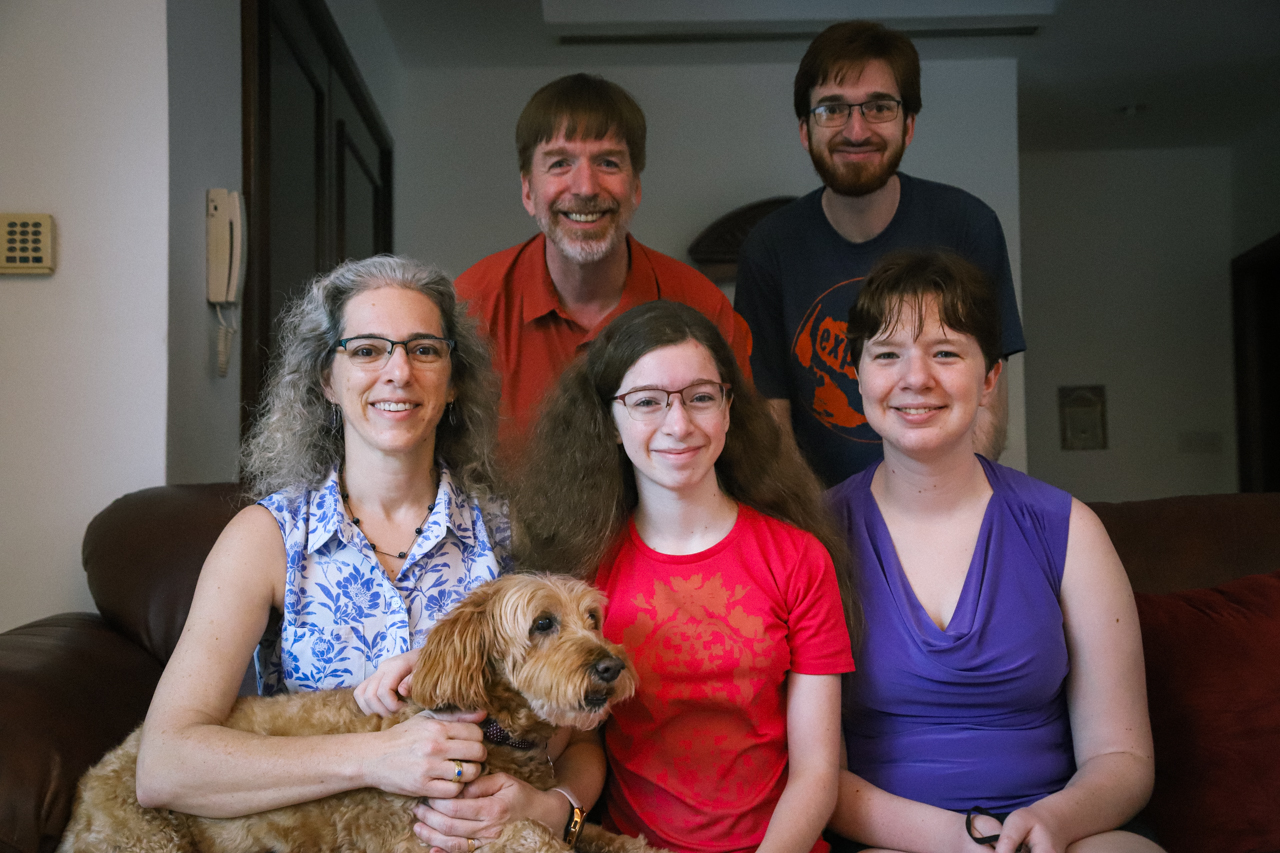

Top image: Michael and Deborah Fripp

All other images: Zachary Tang/Rice Media

I assume that most people don’t know much (or anything at all) about the small American suburb in Northern Singapore. Online, threads like this HardwareZone depict Woodlands as “dangerous” and “infested with gangsters.” And as I skim through the comments of these threads, no one ever brings up the pretty neighbourhood with perfectly mowed lawns.

The only mention of the neighbourhood I found online was a Straits Times video about Halloween on Woodgrove Avenue.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Halloween has been celebrated at Woodgrove Avenue since 2007 when 30 residents got together to share the American tradition,” the article accompanying the video said. “The area has a sizeable number of families from the United States, whose children attend the nearby Singapore American School.”

Growing up, I knew two things about the American community in Singapore: the first, that many lived in Woodlands and had the best Halloween decorations, and the second, that they were a tight-knit and exclusive group.

The latter came from my understanding that the Singapore American School (SAS) only accepted American students or students who had parents working in American companies, and was the only school in Singapore that followed the American curriculum. Perhaps, that explains why, as an international school kid myself, I rarely saw kids from SAS at inter-school sporting events, even less so at social gatherings outside.

The hidden oasis

It took me over 30 minutes on the PIE and BKE to get to Woodlands. Upon exiting the highway, the ‘American neighbourhood’ I remembered from my trick or treating adventure back in 2008 was nowhere to be found.

I had to cruise through rows of HDB blocks and a community club before chancing upon a “Welcome to Woodgrove” sign that signalled I was headed in the right direction.

I met Zach, our photographer, at the entrance of SAS. He barely managed to take a couple of snapshots of the school entrance before being approached by a security guard. After we assured him that we wouldn’t take photos of the interior of the school, we were allowed to continue.

With the floor still glistening from the rain, we continued to stroll through the lanes of Woodgrove. The avenues of houses were empty apart from a group of kids playing football on the street. Christmas and Hanukkah decorations donned gates and doors, while worn basketball hoops stayed propped up on the corners of the streets. A teacher paced behind us, a bag full of books weighing down on her shoulder.

The American high school vibe was more than noticeable. My colleague Shaun, who lives near Woodgrove, had told me how he regularly sees teenagers riding their bicycles home from school—something unusual among local school kids. I didn’t see any teenagers on bikes the day of my visit, likely because it was still the school holiday period, but I did see the occasional generic yellow school bus drive by.

I remember rumours going around when I was a kid that said there once used to be SAS buses with school logos on them. These were allegedly swapped out for the generic buses we see today in an attempt to be inconspicuous and curb terrorist attacks.

After passing a large green field, we arrived at the opposite end of Woodgrove Avenue, where we met Meeta, an American citizen who works at SAS and whose son attends the school.

ADVERTISEMENT

Meeta told me that a lot has changed in the neighbourhood since she first moved here close to a decade ago.

For starters, it’s not as “American” as it once was. In recent years, the pandemic and strict immigration laws have caused foreigner populations to dwindle. This has forced many international schools, like SAS, to take in a more diverse array of students, changing the neighbourhood’s demographic.

And when I told Meeta about the SAS I recalled from my high school days—a secluded bubble distanced from other international schools, let alone local schools—she was hesitant to agree.

“If you look at why the school had to be that way, it wasn’t necessarily bad,” she explained. “Back then, and still today, many American families were moving every two years. They needed schools with a standardised curriculum so that no matter if they were going to Shanghai or Jakarta next, their kids could be on track with school.”

“I remember when we first moved here, the waiting list to get in was very long,” she continued. “But there was a justified reason for that.”

A microcosm of the American dream

All of the families in Woodlands I spoke to moved to Singapore to pursue a better life. They were posted here on the premise that they could bring over their family, live in a suburban home or condo, and send their kids to an American school.

There are little slices of the US sprinkled across this suburb. For Meeta, it’s the school. Everything she likes about the American education system, from the open dialogue encouraged in classrooms to the emphasis on creative learning, can be found there.

“When I enter the school, it’s the same as when I enter the embassy—it’s a little piece of America,” she said. “Everyone smiles or asks you how you are the moment you walk in, even if you’re just walking by each other.”

I didn’t get to visit the school, but I did find a similar slice of America in the home of each family I visited. They each brought to Singapore their own definition of a good American livelihood, and build their lives around it every day.

Merced Gonzales, a 38-year-old mechanical engineer, moved to Singapore from Texas in June 2021 with his wife Linda and their kids. He shared that as a Mexican American, he found Singapore to have the best of both Mexico and the US—he gets the big house and a backyard like in Texas, but also the hawker centres and shops a short distance away like in Mexico.

ADVERTISEMENT

“To us, this is Mexico without the crime,” he grinned.

“Do you have hawker centres back home?”

“They are very similar,” he replied, explaining how the wide array of food choices cooked by friendly hawkers here is very similar to the setup in Mexico.

Michael Fripp, an American who moved here halfway through 2021, also spoke about the many benefits of life in Woodlands.

“Our Singapore house is almost as big as our former Texas house,” he said.

“We love walking at the Sungei Buloh wetlands, running down the T15 trail in Mandai, and bicycling through the Kranji countryside,” said Deborah, Michael’s wife. “We get the best of the big city and open land in Woodlands.”

While both Merced and Michael had predominantly positive outlooks on life in Woodlands, it seemed like a fleeting dream for a wider community of foreigners.

A lonely paradise

For those still here, the pandemic has posed tremendous challenges to integrating. Merced and Michael both confessed that restrictions have made it hard to meet neighbours and build a community. The few socially distanced encounters they have had are a far cry from Meeta’s stories of the pre-pandemic neighbourhood community that organised pilates and yoga mornings at each other’s homes.

When I asked Linda about integrating in Singapore, she shared that she was able to meet a few wives of Merced’s colleagues, but that is all.

“There are a few group chats I’m a part of, too,” she shared.

“There are no activities now, but it is still nice in the mornings as you see everyone walking to school and kids playing in the streets in the afternoon,” Meeta shared.

“It does feel more isolating now, however.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The distance from the city did come up several times with Meeta and the other couples I spoke to, all of them sharing that it does get difficult being so far out when there are so few opportunities to socialise in the neighbourhood now.

“We’re really in the country here,” Meeta laughed.

Integration at its best

When I came down to Woodgrove, I was afraid I would encounter a community segregated from the rest of Singapore, both because of the distance from the city, and due to the different cultural backgrounds of its inhabitants—surprisingly, this wasn’t the case. Everyone I spoke to has become accustomed to eating at hawker centres, getting their daily needs from the mama shops nearby, and running errands around the abundance of HDB flats that surround them.

The beauty of Woodlands is in having both,” Meeta said with a smile. “The school is very American, but our surroundings are very local. If you walk down this street, there are lots of houses. But then it’s surrounded by HDB flats, so it doesn’t feel like Grange Road or those more upscale areas.”

As she said this, I thought of Merced and Michael who had only moved to Singapore a few months ago. Many expats need years before they properly integrate into Singapore. In their case, their families only needed a few months before becoming accustomed to visiting their neighbourhood mall and eating local food.

“When we work from home, we walk to the food courts under the HDB flats on most days,” Michael said. “Good food at a good price. The restauranteurs greet us and know our favourite dishes, and I usually wear my straw cowboy hat to be easily recognised.”

But whether this directly translates to them understanding the local culture is a separate question entirely.

Out of touch, out of reach?

Glass sliding doors separated Zach and me from Michael’s large backyard. Sitting on his tan couch, we spoke to his family about their move to Singapore, and we laughed at our often contrasting views about Singapore.

Michael and Deborah both raved about Singapore’s “great” weather. They also said the roads here are great for cyclers and that they love the number of outdoor spaces. Ironically, as two people who have lived in Singapore for decades, Zach and I are used to hearing the opposite of each point.

While their rose-tinted glasses could be perceived as proof of coming from an isolated bubble, it’s a lot more nuanced than that.

“Their perception is valid even if I disagree to some extent,” Zach said to me as we left their home. “They say bicycling is easy, that the weather is nice; all things most Singaporeans disagree with. It might come across as naive or dense, but perhaps it’s just another valid experience informed by different pasts?”

“And hearing this side of the story is good for us. They show us why Singapore is a haven. Because there’s room for different lives.”

At first, I was hesitant about how I would bring up their views in this article, but my conversation with Zach made me realise that maybe, I was projecting my insecurities as a foreigner onto them.

What we get wrong about bubbles

The stories I heard from the locals of Woodgrove depicted an environment far from an insulated community. Halloween perfectly exemplifies this—to this day, hundreds of Singaporeans travel to Woodgrove every year to soak in the decorations and to trick or treat.

And this year too, despite the restrictions, the locals of Woodgrove managed to put on a show for the Singaporeans who showed up.

“Although the neighbourhood organised a socially distanced trick or treating the day before Halloween, hundreds of people from outside of Woodlands came around to look at the decorations on Halloween day itself,” Michael recalled. “They told us they wanted to check it out even without participating in trick or treating.”

And to their luck, Michael and his family had brought out more than enough to goggle at—giant inflatable dragons, floating ghosts, spider webs, Halloween music, and treats for guests to take home in a socially distanced manner.

There’s an exchange of cultures on both ends—like how the Americans learn to manoeuvre life in a local neighbourhood every day, Singaporeans get to experience festivities like Halloween, Hanukkah, and Christmas in a way different to theirs.

As I discussed this with Meeta, I asked her if she believes the same goes for the students at SAS.

“A lot of the kids have grown up here, having arrived over 15 or 20 years ago. And when they go back to the US, they have a hard time because they have been in Asia for so long,” Meeta shared, as I nodded quietly, thinking of how this sounded a lot like what I have been through as well.

“By and large, there’s a lot of respect for the country and the culture they live in,” she continued.

I may have never known many SAS kids, but the ones Meeta described were not so different from mine. Maybe, just maybe, we have an outlook more similar to each other than I would have previously liked to admit.