Photography by Zachary Tang. Images courtesy of the Asian Film Archive (AFA).

I. Then

Long before she became Cleopatra Wong, the inspiration for American film director Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill Vol. 1 & 2, there was nothing that Marrie Lee wouldn’t risk for love.

In fact, much of her story had been about taking chances and having the guts to just ‘go for it’—never mind the cost or consequences. There were no guardrails on the road toward her dreams. Whenever she fell, she found ways to pick herself back up again.

As much as Marrie loved Life, oftentimes it didn’t love her back.

Born Doris Young in a small kampung in Tai Seng in 1959, Marrie was orphaned at a young age, losing her father at age 6, and her mother at 16. Despite getting good grades in school, she and her elder sister Betty were forced to enter the working world early in order to fend for themselves. At 17, Marrie began working as a receptionist for a nightclub in Shenton Way.

It was the early 1970s, a time when the Singaporean national identity was still being formed. A time of disco and dance halls, with bands like the Bee Gees and The Animals dominating the airwaves.

Movies in Singapore were still big business in the decades leading up to independence. Major film studios like the Shaw Brothers and Cathay Organisation had established their head offices in Singapore since the 1930s, producing local films that were distributed across the region.

At its heyday in the 50s and 60s, Singapore boasted over forty independent cinemas, with theatres featuring a diverse line-up of films. Singaporeans flocked to see the works of Malay actor and filmmaker P. Ramlee, the 1957 Malay horror blockbuster Pontinanak, campy Chinese kung fu action flicks, and Tamil-speaking family dramas. In one weekend, a moviegoer in Singapore could hop from cinema to cinema, from Beach Road to Woodlands, and get a feel of the neighbourhood from the films they saw.

All of this changed in 1965 with Singapore’s expulsion from Malaysia. The hopes of LKY’s founding generation for a united Malayan identity were dashed, and with it, the promise of a domestic economy that was large enough to hold its people’s dreams.

Amidst the invention of modern Singapore, young Marrie grew up idolising Cantonese opera stars like Yam Kim-fai and Pak Suet-sin. On-screen, these women played both male and female parts. They were maternal figures, unrequited lovers, and martial arts heroines who wielded swords and vanquished their enemies.

It was these childhood dreams that led the 17-year-old to respond to a casting call for an untitled film. The poster read:

ARE YOU SMART, SEXY, AND SEDUCTIVE?

“Why yes,” she thought to herself. “I’m at least one of those things.”

To cover her bases, she showed up to the audition dressed in a mini-skirt and go-go boots and tried to figure out how to act ‘seductive’.

The realities of show biz

The first audition with Sonny Lim, the producer, went well. In the second audition, Bobby Suarez, the film’s Filipino director, showed up and asked Marrie to take off her top.

She refused. “I beg your pardon?” she asked.

“I was worried you were going to be difficult,” snapped Bobby. “What are you going to be like on the set?”

Fine, Marrie thought, gritting her teeth. She removed her top. She was on the verge of removing her bra, too, when Bobby stopped her and asked her to spin around.

The two men were inspecting her body for scars and imperfections that might show up on camera.

“Okay we’re done here,” said Bobby. “You’re free to go.”

Marrie put on her clothes and moved towards the door.

“And by the way,” said Bobby. “If you do get the part, you’re going to have to lose some weight. The camera puts 10-15 pounds on you.”

She shut the door behind her, feeling like all hope was lost.

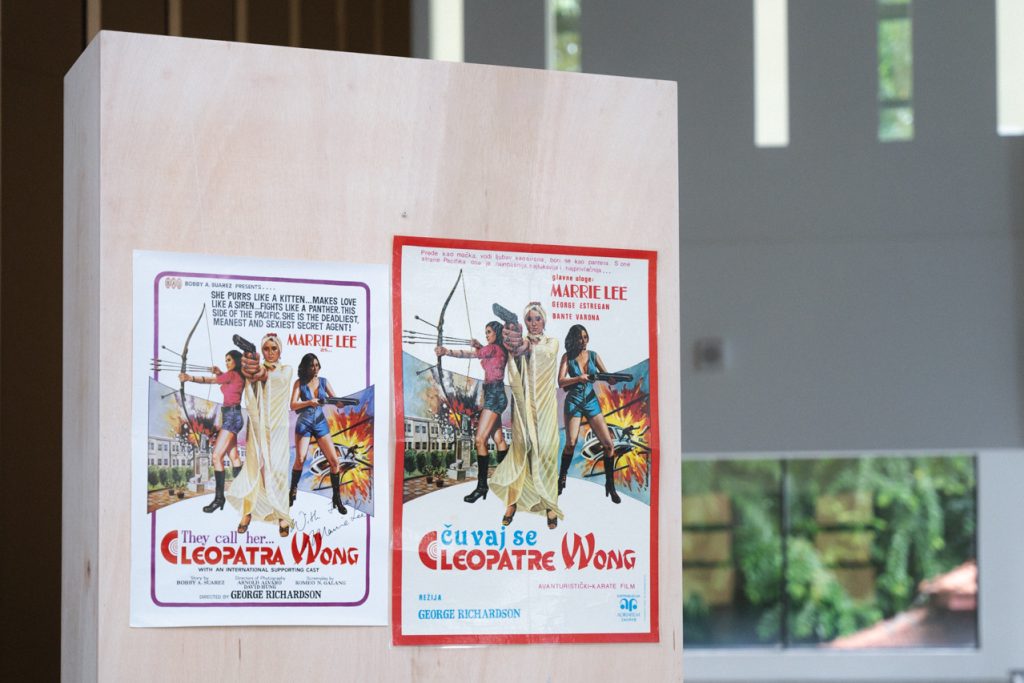

Two months later, an offer to star in the film They Call Her Cleopatra Wong arrived in the mail.

Life on the set

Bobby A. Suarez ran his crew like a pirate ship.

Passports were confiscated. The cast and crew were not allowed to date or experience the nightlife of Manila, Hong Kong, or Singapore. After each day’s shoot, everyone was driven straight back to their rooms—at least so far as Bobby knew.

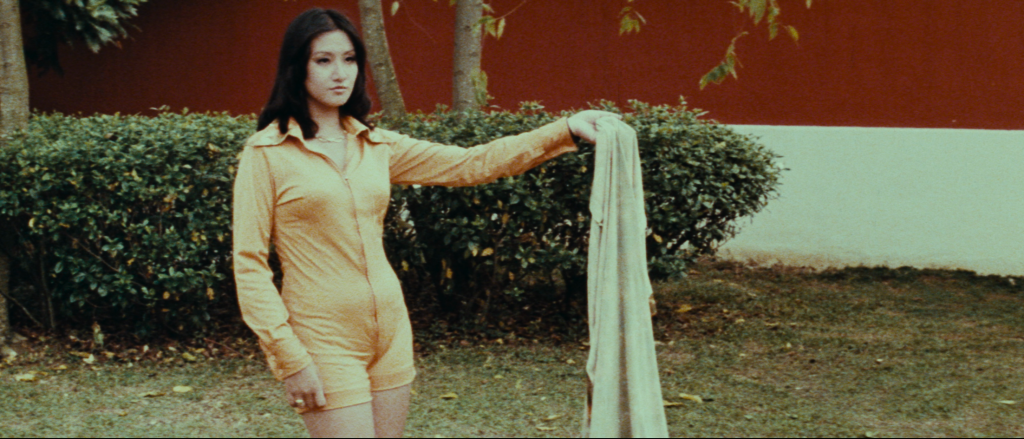

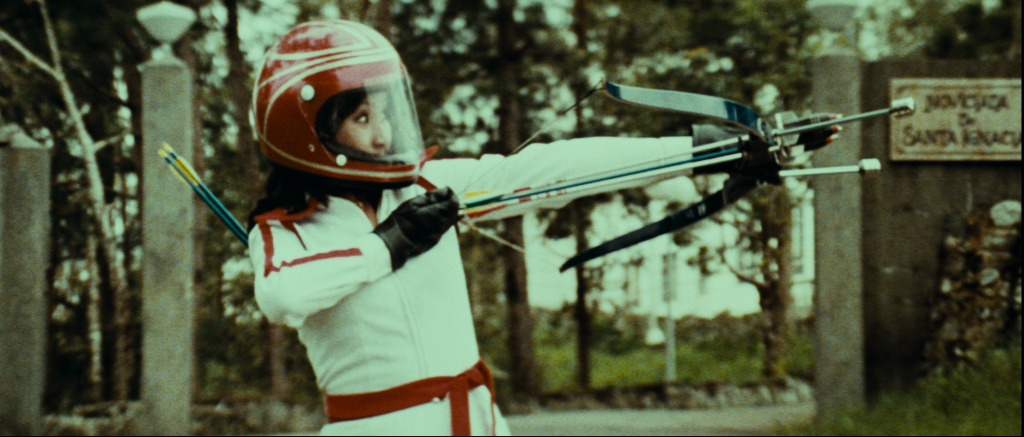

Marrie quickly realised that winning the star role as the sassy and sultry martial artist and top Interpol agent Cleopatra Wong came at a price. Asian filmmaking in the 70s was the real Wild West; safety standards were practically unheard of.

Bobby expected her to perform most of her own stunts, including jumping through a real glass window and dangling on a rope from a helicopter without a harness or safety net.

Unsurprisingly, Marrie sustained injuries. All things considered, she got off easy: just a torn pinkie finger and a fractured left wrist.

“I was considered a bit of a stunt actress,” Marrie told local film blog Sindie in a 2016 interview. “In those days, body doubles were just men in dresses and wigs. So in close-ups, the audience could certainly tell the difference.”

Bobby’s vision was to put Southeast Asian cinema ‘on the map’ for a Western audience. His strategy was simple: make a movie with an ‘exotic’ Asian female lead, shot in exotic Asian cities, but imbue the story with Hollywood sensibilities.

Cleopatra Wong would be his Bruce Lee and James Bond rolled into one.

And the formula worked. Bobby and his producer managed to secure financing to screen the film in tens of thousands of theatres worldwide. From its premiere, Cleopatra Wong created a stir among moviegoers in North America and Europe, which quickly turned her into a global sensation.

Western audiences had never seen an Asian female character quite like Cleopatra Wong. Curiously, the film was also massively popular in the Middle East, with the promotional posters depicting Marrie dressed in traditional Arabian garb.

The film did so well at the box office that it spawned two Bobby Suarez sequels—Dynamite Johnson and Devil’s Angels—with Marrie reprising her role as Cleopatra Wong. After the trilogy, Bobby pleaded with Marrie to sign a contract to make ten more movies together.

But she turned him down. It was 1980, and by this time, Hollywood had come calling. She had been offered the lead role in the film Charlie Chan’s Number One Daughter. Marrie’s dreams of global stardom were on the verge of becoming reality.

Three successive Hollywood strikes in the 1980s put her dream permanently out of reach. The production of Charlie Chan never got off the ground. Meanwhile, in Singapore, the arrival of television and VHS in the 1980s heralded the decline and eventual sunset of the local film industry. The Golden Age of Singapore filmmaking was over.

At her peak, Marrie gave up her career for a chance at a family. By the time another opportunity presented itself again, she was married and her husband said no.

And just like that, Cleopatra Wong faded into obscurity.

II. Now

Nobody knows how well They Call Her…Cleopatra Wong did in Singapore.

No one seems to remember having seen the film at all. I myself was made aware of the film by sheer chance and desperation, as I flailed around blindly, looking for a fresh story idea in Year 2 of Singapore in lockdown.

It was an accidental Google search that led me to an early 2000s interview published by The Straits Times during the promotion of the film Kill Bill, where the director Quentin Tarantino cited Cleopatra as the main inspiration for his heroine.

But when I asked around in my social circles, looking for copies of the movie, no one had even heard of it. Curiously, the film had even been forgotten in director Bobby Suarez’s native Philippines, despite a general awareness among some Filipinos about the rest of his filmography.

Even getting my hands on a copy of Cleopatra Wong was nearly impossible. All film negatives of Cleopatra had either been degraded or destroyed. The full-length film was nowhere to be found online or on Youtube. Besides a few VHS copies and bootleg DVDs collecting dust in someone’s attic, there was little to prove that such a film had ever existed.

In a last-ditch attempt to solve this mystery and find a cure for my pandemic fatigue, I reached out to the Asian Film Archive (AFA) back in June.

A few weeks later, I received this response from AFA’s Executive Director Karen Chan.

Dear Ivan, it read.

It is rather serendipitous that you have written to us about this film. Because Cleopatra Wong has only just recently been found and restored.

The spirit of the roaring 70s

“A lot of young people assume that the older generation of Singaporeans was extremely conservative,” said Karen Chan, when I met up with her at the Oldham Theatre.

“But back then, there were very few age restrictions to go to the cinema. They allowed anybody to watch anything. As a teenager, I watched a lot of racy films that just skirted the lines of pornography. I had a much older brother, who would take me along. He would cover my eyes during the scenes that I wasn’t supposed to see. My parents didn’t bother to control us. Nobody bothered too much back in those days.”

Cinema was just a place for Singaporeans to enjoy and let their hair down. Taking a date to see a Chinese horror flick was just something people did, a rite of passage synonymous with youth, dating and relationships.

On first impression, Karen gave off the vibe of a bookish librarian. But after our interview, it became clear that she was still that young girl who grew up in the 70s and 80s, one who loved going to the movies.

She was also one of the few people in Singapore who hadn’t forgotten about Cleopatra Wong.

So back in 2016, as AFA’s Executive Director, Karen put out an open call to film archives around the world, hoping to recover the movie that Singapore had lost.

The initial response wasn’t promising. AFA learned that all the film negatives of Cleopatra had either been degraded or destroyed in Asia, a region that had never prioritised film preservation until recent decades.

But then, they made a discovery.

A 16mm copy of Cleopatra Wong was found at the Danish Film Institute, albeit in pretty bad shape and with Danish subtitles burned into it. Months later, a German-language 35mm print was found at the Filmarchiv. The film was repaired, cleaned, and digitally scanned in a lab at the Haghefilm Digitaal in the Netherlands. But many frames from the original print were still missing, and there was no one the AFA team could consult to piece the puzzle back together. How was the film supposed to look? What was the colour grade of the original print?

There was now no one left to show them the way. Bobby Suarez had passed away in 2010, and with him, his vision for a Southeast Asian cinema would shock the world.

“Our team managed the best we could with our limited resources,” explained Karen. “But it’s quite a shame that we, as archivists, were forced to make artistic choices on behalf of the original filmmakers.”

“This whole experience really speaks to the importance of film preservation in Singapore. Because once it’s gone, people today will have no record of those times.”

If the spirit of Singapore in the 70s could be summed up in one word, it would be: experimental. Everything about the nation-state was in flux, and from that uncertainty, creativity flourished.

“A lot of the films that we consider cult films today were simply Singaporean creators trying new things. You see this in Cleo too.”

What was different about Cleopatra Wong was that she was an Asian woman who was very powerful and smart, but also completely confident in her femininity and sexuality. She could do anything and everything, while still projecting the soft, feminine traits that were seen as sexy at the time.

“At AFA, when we screen some of these old films from the 60s and 70s, young people are surprised at how creative and entertaining these movies are,” said Karen.

“Take some old Malay films as an example. People were shocked at how daring the directors were—their portrayals of women, and some of the issues they touched on, which were very controversial, even by today’s standards.”

At the end of the interview, I wondered aloud how Cleopatra must have felt back in those days.

Karen smiled.

“Why don’t you ask her yourself?”

III. Finally

I was put in touch with Marrie Lee via her Yahoo email account, where she goes by the screen name Shadowgail.

As Zac, the photographer, and I waited downstairs at a quiet HDB block in Simei, where Marrie lives with her sister Betty, I tried to imagine what she’d be like in person. Would I recognise her as the same girl from the movie?

But the Marrie who showed up was not the Cleopatra Wong I’d been expecting.

Life had dealt her more blows. She was only in her early 60s, but multiple strokes she suffered in 2013 had caused long-term damage to her health. This was followed by a diagnosis of Bell’s palsy, a condition that affects the facial nerves.

These days, Marrie has trouble walking long distances, her speech slightly slurred. Wearing a mask during this pandemic had made it especially difficult for her to breathe.

But Marrie didn’t need anyone feeling sorry for her. When she found out about her diagnosis, she channelled her energies into becoming an independent film director, where she wrote, directed and starred in a low-budget independent film Certified Dead (2016), which dealt with themes of death and second chances.

In the cab ride to our first shoot location, she was more reserved than the Cleopatra Wong I had been expecting. I tried to make small talk to break the ice.

At one point, I remarked how Singapore was on the verge of entering the third year of the pandemic.

“Yes, it’s very boring,” answered Marrie. With her pre-existing condition, the sisters had mostly confined themselves at home, rarely venturing out further than their neighbourhood.

Where had all of the time gone? To what purpose?

“The years, they just fly on by without you noticing,” said Marrie, staring out the window.

Singapore: Past and present

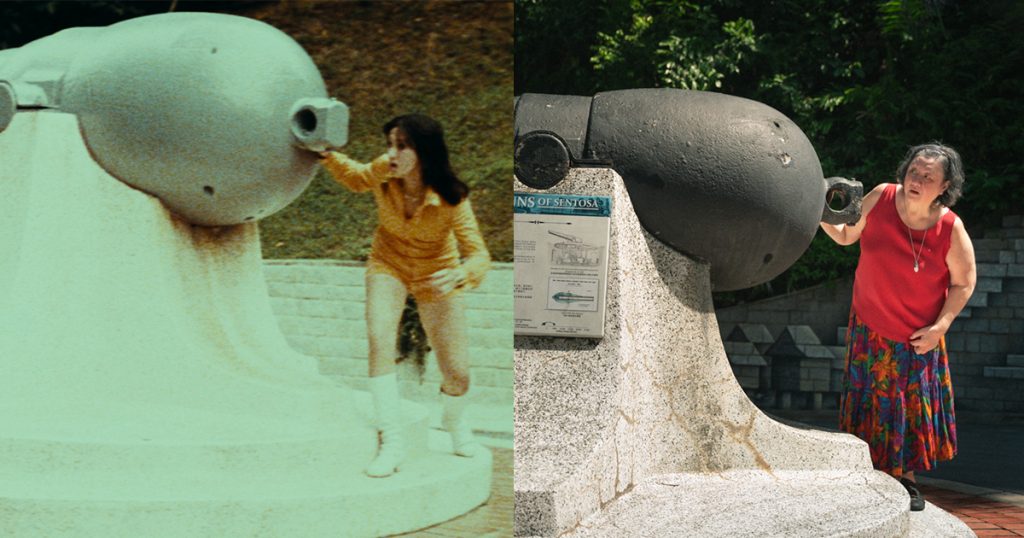

The plan for our outing was to revisit some of the shoot locations from the film and recreate some of the scenes.

Our first stop was the cable car from Mt. Faber to Sentosa, where an extended chase scene was shot.

As we waited for a yellow cable car to match the one in the film, Marrie recounted how on set, Bobby had made her ride the cable car dozens of times just to get the perfect take.

“The chase sequence was great fun!” Marrie recalled. “I remember Bobby yelling at us multiple times for horsing around on the set.”

Back in the day, Sentosa had just opened up as a pleasure resort for locals. Many of its old attractions have now been replaced by newer, shinier venues catering to an international crowd.

When we hopped on the cable car and began the photoshoot, I was delighted to see Marrie suddenly come to life. Despite her condition, her facial expressions mirrored the young Cleopatra almost exactly. It was as if no time had passed at all.

But by the time we stepped off the cable car, Marrie had to excuse herself to the restroom. The 10-minute ride had made her dizzy and nauseous.

Our next stop was Fort Siloso. Due to Marrie’s condition, the Sentosa staff were kind enough to provide a buggy for our ride up the hill, where Zac snapped photos of Marrie hiding behind a cannon to escape an international syndicate of criminals.

The yellow one-piece and go-go boots in that scene was not the skimpiest outfit she wore on set. A completely topless love scene had actually been left on the cutting room floor.

But the scene that most embarrassed Marrie was a poorly-conceived stunt filmed at Chinese Garden, where Cleopatra had to leap over a 20-foot wall to escape a contingent of wrestlers and karate practitioners.

“They attached a wire to me for that scene,” recalled Marrie. “It looked totally ridiculous, and I used to squirm in my seat when the audience would burst into laughter in the theatre.”

After a quick photoshoot at the National Gallery, the site of the Old Supreme Court, we sat down at the gallery cafe for an afternoon coffee and had our first real conversation of the day.

I learned that since the 80s, Marrie had been married and divorced three times. In one marriage, she was the stepmother to Shirkers director Sandi Tan. By sheer coincidence, Shirkers (2018) is also a story about a lost film, one that garnered more attention abroad than in Singapore itself.

Marrie’s Love Life

Prior to her marriages, Marrie had many boyfriends, including dalliances with her Cleopatra Wong co-star and onscreen love interest, the Filipino actor Franco Guerrero, as well as a brief flirtation with her stunt double.

In fact, there were no limits to what she was willing to do for love. In 2000, she gave up smoking cold turkey for a boyfriend, who hated the smell of cigarette smoke getting on his clothing. As she was sweating out her withdrawal symptoms one morning, she saw that her boyfriend was eating a bau from a neighbourhood stall for breakfast.

“I remember he was saying something to me,” said Marrie. “But I was only paying attention to that bau in his hand.”

Over the next two months, she consumed over 100 baus until she quit her nicotine habit for good. A few months later, she quit her boyfriend too.

Nowadays, Marrie lives alone with her sister Betty in their Simei HDB flat. She has no regrets and has come to terms with everything that life has thrown her way.

Despite always wanting a family of own, she was diagnosed with a rare congenital abnormality—a double uterus—which meant that she could never have a baby.

From time to time, when she feels nostalgic, she still puts on her VHS copy of Cleopatra Wong. It brings back fond memories of a Singapore she once knew intimately.

“They’ve torn some buildings down and changed the names on others,” she said, in the cab ride home.

“I hardly recognise this city anymore.”

IV. Forever

“Well, if I can’t find them, let them find me.”

Cleopatra Wong

Up to this point, I haven’t even told you what the movie is about.

Because Cleopatra Wong is not meant to be described. She’s meant to be experienced.

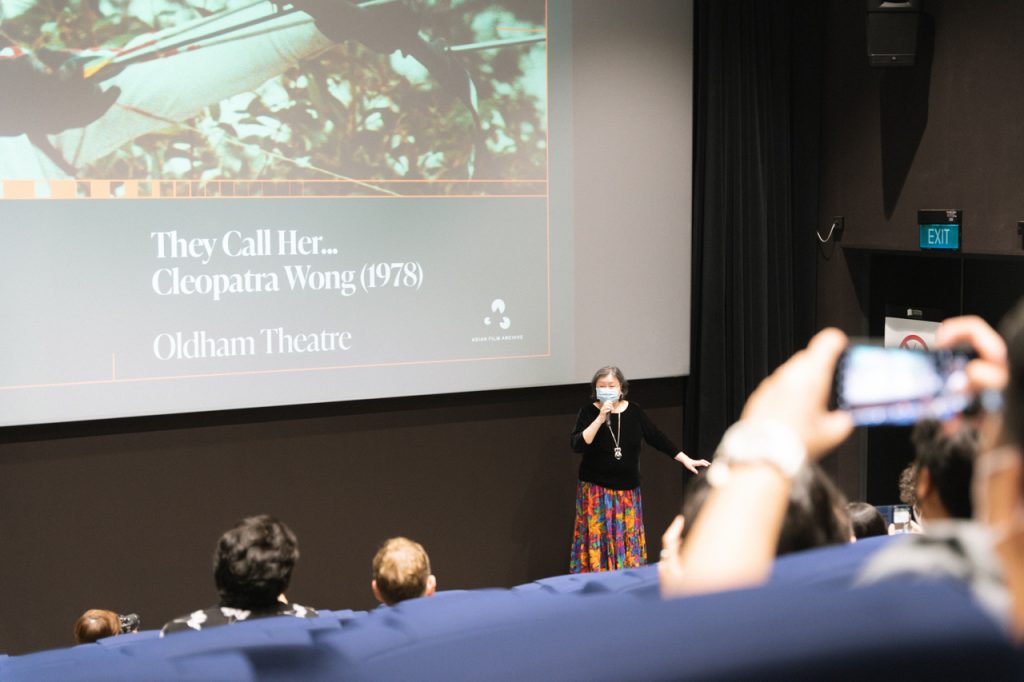

On 11 September, Zac and I attended the global premiere of AFA’s restored film print of They Call Her…Cleopatra Wong at the Oldham Theatre. Because of the pandemic restrictions, the theatre was screening to a sold-out audience of only 50 people. Before taking my seat, I scanned the audience. Even behind the masks, I could tell that it was mostly a foreign and alternative crowd.

Before the screening, Marrie gave a brief introduction, reminiscing about the drunken nights back on set in the 70s with Bobby and the cast and crew. They were all misfits, dreaming the same dream.

Then the lights were dimmed, the projector whirled, and Cleopatra Wong started to play.

Afterwards, outside in the night air, I watched the cool kids light up cigarettes. They were all talking about the film they had just seen.

I turned to Zac and said, “I can’t remember the last time I had so much fun at the movies.”

Fun. Remember fun? I miss that. The uproarious laughter. Serendipitous encounters. The sense of community from experiencing something together at that moment, for the first time.

Karen and the AFA team had achieved the impossible: they’d brought Cleopatra back to life, in full colour. Every frame and every expression was so beautifully executed and clear. Thanks to their efforts, Cleo had been resurrected, and now she was going to live forever.

By the 1980s, the Shaw Brothers and Cathay moved out of Singapore, leaving for the shores of Hong Kong to spark a new creative filmmaking movement. Most of the independent theatres in Singapore either went bankrupt or became cineplexes. Today, they show the same Hollywood franchise movies in every neighbourhood.

“The forces of globalisation changed Singapore far more and far faster than some of the other Asian Tigers, precisely because we were so small, and relied almost entirely on the international market to survive,” explained Karen.

“In the process, Singapore was forced to let go of some of our local flavours. We lost touch with how we saw and portrayed ourselves. Hollywood and the rest of the world flooded in. How could our local film industry withstand that tidal wave? There was no way.”

Even as I wrote this piece, I felt somewhat at a loss. I don’t know whether I’ve done this story justice, or if anyone else will care. Logically, this film shouldn’t mean more to me, a foreigner from Taiwan, than it should to Singaporeans themselves. But in many ways, that’s exactly what’s happened; Cleo was loved by international audiences but forgotten by the country that produced her.

I believe that there’s a thread that connects every story together, forming a tapestry that intertwines the past, present, and future. It will never be finished. It will always exist in that liminal state between making and unmaking. Like our own stories, our identities are also fluid. And history is both a record of who we were and one that changes depending on how we choose to interpret it today.

What was Cleopatra’s takeaway from her own story?

“Guts,” said Cleopatra. “You must really have the guts to just do it. To be self-sufficient. Have the courage to start over, to build something from the ground up again.”

“Storytellers today need to dig deeper,” said Karen. “To connect to a wider audience—not just a small group of film buffs. They also need to think about how their work will be remembered and preserved. It’s ironic that in the digital age, we’re losing more than ever before. Technology moves so fast; formats quickly become obsolete within a few years.”

“Once these works are gone, there will be no record of our lives for future generations.”

Amidst Singapore’s identity crisis, maybe Cleopatra Wong is the heroine it needs.

She was always right here: a young, starry-eyed girl of seventeen, just waiting for the audience to fall in love with her again.