All photography by Liang Jin Tey for RICE Media.

I was sipping on a glass of Taittinger, staring at the two slabs of seared foie gras in front of me. Wobbling slightly atop the toasted sourdough bread like savoury jelly, they were served with a generous sprinkling of dark brown crumbs and some fruit puree to provide a subtle medley of flavours—from smokey and nutty, to tangy and salty.

Next, a small mound of caviar and unagi, bathing in a bowl of bright amber liquid, was placed in front of us. Visually stunning, this Burmese-inspired broth was laced with ginger oil, but also surprisingly light and restrained on the tongue.

But here’s where it gets interesting: this was no ordinary dinner in an upscale restaurant. Sure, the tastes and textures felt comfortingly familiar, and the service was impeccable, but dig a little deeper and you’ll discover that not all is as it seems.

The gritty brown stuff on the foie gras is moromi, a minimally processed by-product of soy sauce production. The soup, meanwhile, is cooked by boiling banana stems, which are typically chopped off and thrown away once the fruit is harvested. Heck, even the salts garnishing the dishes are made with crushed eggshells.

Welcome to WellSpent Evening, a culinary event focusing on sustainability. Organized by a trio of enterprising R&D chefs at a local chef’s academy At-Sunrice, this dinner was all about upcycled cuisine—in layman’s terms, food made from edible scraps.

Although it’s been touted as a popular trend to watch this year, food upcycling is still very new to Singaporeans. There are several commercial food upcycling initiatives in the city, like local grocers Treatsure and Ugly Foods and beverage company the Crust Group, but so far, none have attempted to organise an event of this scale or ambition.

The seed for the idea was planted at the 2018 World Chef’s Congress three years ago, when the founder of At-Sunrice, Dr. Kwan Lui, attended a talk by Hervé This, the father of molecular gastronomy.

“He was giving a talk on note-by-note cuisine, which is a radical way of cooking using science instead of typical ingredients like meat or rice,” she said. “With note-by-note, Hervé strips each ingredient to its basic compound-like flavour and colour before reconstituting it to invent a new dish. This process can feed more people, prevent food spoilage and save energy. Some has called it the future of food.

Dr. Kwan was so impressed that she invited the food scientist to Singapore for a week. Hervé proved to be an enthusiastic teacher, whipping up two dinners over the course of his weeklong visit. While the chefs at At-Sunrice were inspired by the philosophy behind note-by-note, they were also perplexed. Compounds were, at the end of the day, still chemicals and not real food.

Then, Dr. Kwan had an eureka moment when she chanced upon an article about food upcycling. By using an approach similar to note-by-note, entrepreneurs are now able to repurpose food waste.

“It really resonated with me,” she said. “I thought it would be a very impactful mission for our students. For 20 years, we have qualified thousands of passionate culinarians into the world of food service profession. They buy, they cook, they serve and they waste. By advocating upcycling, I could connect the other half of the circle, making it a circular economy.”

Kwan was onto something.

Food waste has grown around 20% in the past decade in Singapore, according to a government report. For a little city that imports over 90% of its food, churning out about 744 million kilos of food waste—that’s equivalent to about 51,000 double decker buses—in 2019 alone is not just alarming, it’s scandalous. Over 40% of this food could have been upcycled but wasn’t, stated another report by the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore.

As such, the argument for upcycled foods was irrefutable: it was cost-effective, it was earth-friendly, and there was plenty to go around. But amid all the buzz lay a million-dollar question: can it ever appeal to the masses?

“I think our biggest challenge was to figure out how to excite Singaporeans using ingredients that would’ve otherwise not gone to human consumption,” said chef instructor Gn Ying Wei.

Gn and her colleagues, senior chef Kelly Lee and food technologist Tais Berenstein, dreamed of one day organising a series of events unlike anything Singaporeans have ever seen, with a lofty goal of introducing upcycled foods to the public in a fun, palatable way. This special day would commence with a pop-up produce market, and continue with a flurry of workshops, before culminating in a six-course dinner worthy of a Michelin-star restaurant.

The trio began by sourcing food waste like crustacean shells, banana stems, moromi, coconut fibre, and fruit peels, among others, from different food manufacturing and F&B companies. Several companies were initially concerned by their request, but many were happy to oblige after the chefs explained their mission.

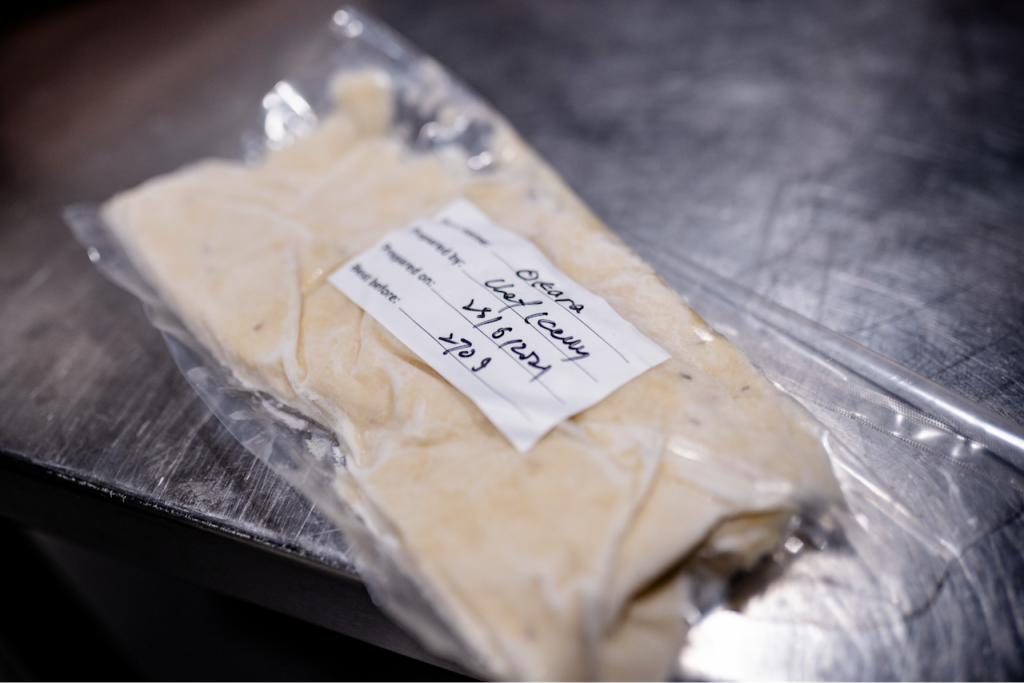

“We wanted spent products that would create a huge negative impact on the environment if they were discarded, like okara, which is the nutritious top layer that gets scraped off and thrown away in tofu production. One tofu factory alone can produce up to 300 tonnes of okara waste a month in Singapore and it’s polluting our waters,” said Berenstein, adding that spent (or used) ingredients sometimes possess higher nutritional values than their raw counterparts.

To ensure that these food wastes were clean and safe for human consumption—a lawsuit for breaching food safety protocols would surely be the death knell for their project—strict procedures were employed in their handling and shipment. For instance, okara turns bad easily, so the product needs to be transported swiftly and refrigerated immediately upon its arrival to the academy.

And then there’s the issue of turning these wastes into food-grade products. The team spent their waking hours hunched over desks and kitchen counters, playing and experimenting with these ingredients, even sending some to a lab to be analysed. A small number of these were further processed using methods like drying and fermentation.

After several months of hard work, a breakthrough happened.

The chefs were elated when they found out how versatile okara was—it could be turned into soup, hummus, or even noodles. Moromi, they also discovered, was an umami bomb, and can be used as a substitute for salt because of its lower sodium content.

“Ideally, we would like to use as much upcycled ingredients in our foods as possible,” said Gn. “The marmalade I made, for instance, uses purely tangerine peels. However, sometimes that isn’t always possible. The cookies get too grainy and crumbly when there’s too much coffee in it. So we aim for at least 10%.”

Taste was, of course, paramount.

“Our food needs to be delicious,” said Gn. “Take fruit peels for instance. The Chinese would traditionally dry these peels but the process makes it bitter. Fortunately, I managed to find a way to turn it into a marmalade after plenty of trial and error.”

Fast forward to the day of reckoning. At the morning market, a handful of curious visitors gathered around food stands, sampling ordinary-looking dishes that were, by every means, extraordinary. There was nasi lemak made from coconut fibre rice, and curry made from the pulp of a jackfruit husk. There was also moromi burger, popsicles made from fruit peels, as well as cookies and cakes flavoured with spent tea leaves and coffee, a by-product of brewing these beverages.

The real wizardry, however, took place that evening, during the formal six-course dinner in the academy’s kitchen-cum-experiment-lab. More than a dozen diners, including a few notable figures in Singapore like accomplished head chef at Esquina, Carlos Montobbio, and sustainability advisor to INSEAD, Stephane Benoist Maitre, had shown up for the evening’s second seating and were now waiting in anticipation as a procession of dishes came cruising down the aisle towards them.

Together, we would be upcycling 30 kilograms of raw spent produce.

The fourth course—a dish called Art de Choke—had been suggested by none other than culinary wunderkind Andre Chiang, who has also been dabbling in upcycled cuisine in the past year. Chiang has been working closely with the team as an advisor for several years now, and is as passionate about sustainability as they are.

“When it comes to artichokes, only 20% is used in cooking while the rest are discarded,” said Lee. “However, I was able to use more parts of the artichoke so two artichokes can now feed five people. By breaking it down into different compounds, I was able to extract its flavour and bind it back to look like an artichoke.”

I popped it into my mouth. It didn’t really taste like any artichoke I knew of, but it was a good try.

The final savoury dish was the okara noodles. Made from 20% okara, it was drenched in a salty dark sauce made from spent prawn shells, and perfectly al dente.

These dishes looked simple and effortless enough, but Lee said that they were some of his most technically challenging work in his decade-long career. “Many of these dishes require specialized equipment like centrifugal machines and rotor evaporators. Since we can’t afford any of these, the whole extraction and cooking process is really tedious.”

As we adjourned to a different room for our upcycled desserts that evening, I felt buoyed by a sense of hope. Upcycled foods may draw plenty of skeptics in Singapore, but here was a group of people who were passionate about what they do. They were still learning, but their enthusiasm was contagious. It would only get better, and more accessible, from here.

“I’m positive upcycled foods will one day be a part of our diet,” said Gn.

“Take Singaporeans and NEWater. They were opposed to it at first but look at them now. It’s the same with upcycled foods—you wouldn’t know that you’re eating it in the future, but it’s in there.”

The next Wellspent dinner will be held on Aug 8, 2021. Visit this link for more information.