This article is part of our new series on burnout, Running on Empty. Watch the second video in the series here.

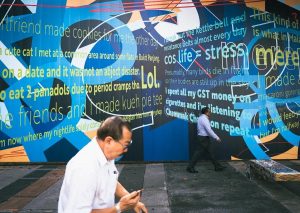

Images by Liang Jin Tey/RICE file photos.

Earlier this month, one of my colleagues wrote an op-ed arguing that the cure for burnout is to lower one’s expectations.

He made a lot of good points, ones I agree with: for example, that it’s disingenuous to expect things to change if employees don’t make a point of communicating problems, and that Singaporeans’ poor self-advocacy skills and conflict aversion only make this worse. He’s also right that responsibility for one’s happiness and well-being ultimately lies with ourselves and no-one else.

However, what we don’t see eye to eye is on where the root cause of burnout lies, and who is best placed to address it.

As such, I want to make the opposing case: that while burnout afflicts people, its primary source is organisational—the practices, systems, and cultures adopted by workplaces and industries. As a systems issue, fixing it must start from organisations themselves.

Burnout Is An Occupational Hazard

The official definition of burnout—yes, one exists—makes it clear that it has to do with workplaces, not people.

In 2019, the World Health Organisation (WHO) updated its definition of burnout. Their guidance states that while people might seek treatment for burnout, it is not a medical condition, but an occupational phenomenon—a syndrome which arises from “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed”.

This clarification signals where our focus should lie. Occupational phenomena, by definition, have to do with jobs, from the expectations attached to working in a particular field to its attendant hazards. People can take steps to improve their relationship to their work, but this doesn’t change the environment they’re working in.

There’s a whole sea of research, from academic studies to empirical surveys, which has tried to identify what causes burnout. Some of these are personal reasons, like a fundamental mismatch between the person and the job, but many others have to do with organisational context.

A Gallup survey of US workers from 2018 lists the top five causes as unfair treatment, unmanageable workloads, lack of role clarity, insufficient support from managers, and unreasonable time pressure—none of which have anything to do with individual workers.

I couldn’t find a comparable local survey, but anecdotally, Singaporean workplaces seem to be plagued by similar problems (there are, of course, plenty which articulate how our workers rank amongst the most stressed and unhappy in the world). Poor practices, overwork, unrealistic demands, and a lack of recognition or reward, it seems, are woes of workers everywhere.

You Can’t Change What You Can’t Control

Many of the factors which contribute to burnout aren’t things which individual employees can address, especially if they are chronic and structural, affecting whole swathes of workers in a company or in a particular sector. If anything, feeling powerless to change one’s circumstances contributes to burnout in the first place.

Take the medical profession, for example. Junior doctors in the public healthcare system—the subject of our latest video in our series on burnout, Running on Empty—work notoriously long hours, with many clocking over the limit of 80 hours a week. Some of this arises from how the underlying system of office hours is set, exacerbated by low pay, difficulties with taking leave, and senior staff who take a ‘we went through it too, so you should just deal’ approach.

Or teachers, who, on top of juggling actual teaching, pre- and post-class work, and myriad other administrative tasks, also have to deal with being ‘always-on’—communicating with students (and often, their parents) after school hours, and sometimes on weekends and holidays.

Bureaucracy and middle management might make things worse in large organisations, but small companies face their own set of problems, too. For example, they face the resource constraints that come with running a tight ship; there are only so many heads to distribute work amongst, and less room to cushion low periods.

However, from an organisational standpoint, it’s not always reasonable to look to employees for answers. We might be able to identify where things are going wrong, but we don’t have access to all the information necessary to find long-term solutions, or the decision-making power to implement them.

The people who do? Employers.

Ultimately, if both the causes and effects of burnout are collective, then focusing on individuals instead of systems isn’t going to help. Telling employees to set better boundaries, or leave if a place is simply too toxic, is only going to work up to a point. The focus should be on encouraging people to stay by ensuring they’re well looked after.

Employers Need To Look At Systems, Not Employees

To be clear, I don’t see this as an all-or-nothing binary, with all the onus falling on employers and no room for employee responsibility or accountability.

Part of it is up to employees, too—to set boundaries, communicate problems, and advocate for ourselves when our needs are not being met. It’s on us to practise self-awareness, make the call to leave jobs which don’t suit our needs or well-being, and not use work as a distraction to avoid dealing with problems we don’t want to face.

All these, however, are quite different from managerial inaction on organisational problems, which could reasonably be fixed with some upstream changes.

For instance: set achievable targets. Ensure there’s enough manpower for all the work which needs to be done. Devise clear channels for feedback—and don’t shoot the messenger if negative responses are received.

Penalising employees who speak up about burnout for being ‘incompetent’ or ‘rocking the boat’, or gaslighting them into thinking it’s their fault for not managing better, only encourages cynicism. After all, if no-one’s going to take you seriously, why bother saying anything?

It’s trite to say that managers ought to lead by example, but it does make a difference. One friend, a former secondary school teacher, recalled that while many of her colleagues struggled with overwork, having a compassionate principal who understood how problematic practices might cause burnout made a big difference to morale.

Even things like ‘day off’ policies require some thought: they have to suit both the company’s and employees’ needs, and workloads have to be adjusted to to accommodate this. There’s no point telling employees to take a break if people have to work overtime on either side of the break, or work through the break, to get things done.

Employee-focused programmes like mindfulness and learning to ‘just say no’ are valid, but these are ultimately coping mechanisms, not company-oriented strategies. There is nothing more demoralizing than being fed meaningless platitudes like ‘take a day off’ when you know that fundamentally, nothing has changed, and you’ll be going back to the same system which wore you down once that temporary reprieve is over.

RICE has struggled with staff burnout for a while. It’s an ongoing, incomplete process of figuring out how to make things better, but in my experience, there was a difference after changes were made to company practices this year, after the dumpster fire that was 2020 made it undeniable that existing ones weren’t working.

For example: company policy was updated to make it clear that messages after 6:30 PM were considered non-urgent, managers were more active about reminding people to take off-in-lieus (and taking leave themselves), and workflows and targets were re-assessed for sustainability.

In fairness, these were accompanied by an active decision to take better care of myself, and decide what compromises I was no longer willing to make: no more cancelling plans at the last minute, no more staying up till 3:00AM trying desperately to crack a piece. I felt freer and more able to do this, however, knowing that underlying practices were finally changing, and I wouldn’t be going back to the same old problems again.

One person might be an outlier, two a coincidence, but several is a pattern, and anything more is an issue of systems and cultures, not people. If businesses can’t function without compromising their employees’ mental health, they should reevaluate whether they ought to be in business in the first place.