What does identity mean in this polarised age of digital spaces and constant absorption of outside stimulus?

This is a question I’ve been asking myself for a while, at a time when who we are seems to be defined by our outward reflection of cultural values, personal interests, and the direct action we take in person and online. From the infographics people post on their insta-stories to the seemingly endless debates started on Facebook threads, more than ever it seems like we are willing to vocalise our personal beliefs and present them as inextricable parts of their identity.

This idea that we compartmentalise parts of ourselves through digital imprints fascinates me—it is through social media that we can observe how identity seems to constantly morph for some people, especially in response to the increased visibility of certain social causes.

The two films featured in Programme 2 of the Singapore International Film Festival’s New Waves series, Taboo (2019) directed by Charlotte Lim Lay Kuen and Calalai: In-Betweeness (2015) directed by Kiki Febriyanti, unravel these issues around identity. They do not directly address the effect of digital spaces, but through the genre frameworks they adopt, two relevant truths can be found: that identity is an entity that the individual wrestles with and can never truly comprehend, and that identity, especially in relation to gender, is constantly shifting unrestrained by societal norms and binaries.

In the simplest sense, Taboo can be interpreted as a story concerning the constant push and pull between feelings of freedom and entrapment in restrictive environments—in this case, the religious village of the girl. The film concerns itself with establishing certain contrasts, urban environments like cafes versus lush rural forests, societal acceptance versus rejection, and the visual contrast between black and white and colour. These contrasts mirror the internal conflict within the girl and the difficulty with which she parses through her own sense of identity, represented visually by images on screen that overlap like ghostly visages.

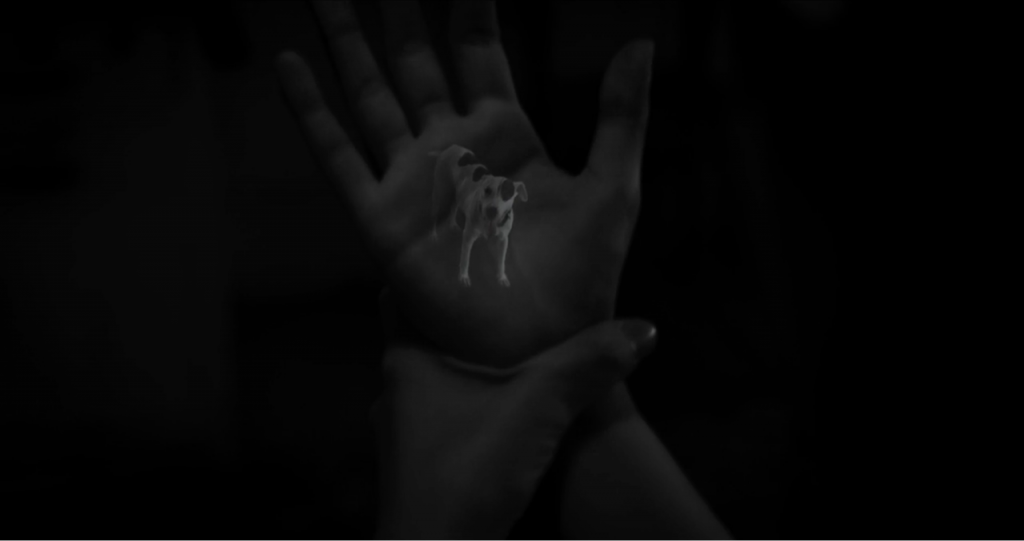

The most prominent image is that of the dog standing in her palm, appearing to be a projection of sorts that she continuously hides with shame. Through these elements, Taboo can be seen as a film about how our personal identity is dictated by outside forces, like religion and communal ties, uncontrollably imposed at birth, creating labels we are forced to wrestle with.

It’s easy to see the societal rejection the girl faces (from merging with the dog; seen in Islam as haram) as a metaphor for the persecution women everywhere face for a litany of things, whether in lifestyle or appearance. As such, the intense ending of the film comes as a reprieve, with the girl slowly fading into a brick wall and appearing, in colour, in a green utopia where she is free to roam and interact with said dog.

The style of editing and presentation of locations can admittedly be confusing on first watch. It took me until the second viewing to really understand that the film was being told linearly, but to me the confusion aided the emotional qualities of the film. The abrupt shifts between scenes, the atmospheric dark lighting and surreal unexplained images reached into a place in my psyche that I was not entirely comfortable exploring.

In one scene, the girl is on the floor praying, her back facing the audience as a separate image soon appears of her front to the left of her, her face in a different position, floating, seemingly deep in thought. This manifestation of the girl’s internal and external self moved me; it made me ponder how much of our identity is merely performative, and how much we can truly grasp of ourselves internally no matter how opaque.

Tropical Malady takes the approach of segmenting itself into two parts, the first presenting the straightforward narrative of a burgeoning homosexual romance within an urban space, and the second appealing to the depths of the human psyche, presenting a confrontation between a man and a tiger shaman within the jungle. On the other hand, Taboo appears to blur and amalgamate these two distinct paths, cutting back and forth between urban spaces wherein the girl’s struggle is tended to sensitively by her peers, and rural areas where she is cast out and forced to grapple with her identity. The resulting film is entirely beguiling, and while Weerasethakul presents the psyche as having an accessible exterior and mystifying interior, Charlotte Lim posits that both work in tandem, emphasising our inability to ever fully grasp the intangible nature of personal identity.

Director Kiki Febriyanti takes a no frills approach, having no prominent voice in the documentary and leaving everything to be dictated by people within the Bugis community, sharing their own cultural history and experiences. The documentary is loosely structured around the experiences of a few people who are biologically female, the most heavily featured being Prof. Nurhayati Rahman M.Hum, a Professor of the faculty of Cultural Sciences at Hasanuddin University in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Prof. Nurhayati starts the documentary by explaining the main concepts explored in La Galigo, the bible for the Bugis before Islam was widespread, she explains that it tells the story of three worlds, Bottilangi, the upper world (the sky) which symbolises masculinity, Buriliu, the under world (the sea) which symbolises femininity and lastly, the middle world where there is a marriage between masculinity and femininity. It is this middle world that the documentary takes the most interest in, as it provides the basis behind the idea of there being people in between men and women.

The five genders recognised in their culture are as follows, men, women, Calabai (people who are biologically men but who are closer to women, having feminine characteristics), Calalai (people who are biologically women but have the instinct and character to become a man), and Bissu (those who do not belong to any gender group, as they assume the role of God, who is genderless).

One such subject is Syam Suryani, the Parenreng village head who is shown going around and tending to the needs of villagers. There is a fluidity presented to what is expected of the tasks stereotypically assigned to each gender, with neither men nor women predominantly handling domestic or social issues. A saying that is recounted is “even when he is a male if he behaves like a woman then s/he is a woman on the other hand, even when she is a female if she behaves like a man then s/he is a man”. It is clear that there are traces of a binary being acknowledged, an example of which being Marni, who acts as a carpenter and identifies as a Calalai as she states that she is more suited to male tasks. Yet in practice it seems like the Bugis society operates on an extremely open-minded and progressive level with anyone being allowed to adopt any profession without discrimination or having to conform to twisted perceptions of gender roles.

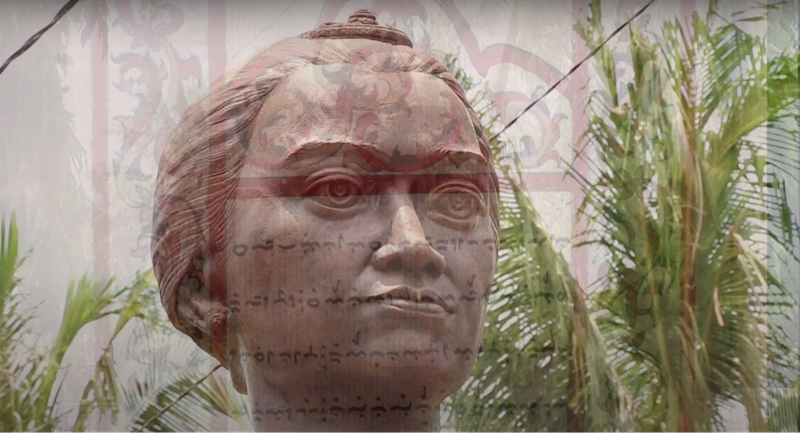

By comprehensively going through cultural experts, the documentary effectively paints the portrait of a society where gender is a fluid concept to be taken with an open mind. In the age where transgender and nonbinary people struggle to make society at large understand them with a degree of compassion, there is something gently affirming about how Calalai purports these ideas surrounding gender as not explicitly modern concepts, but also the cornerstone of ancient systems and beliefs. This is best seen from the documentary’s exploration of Retna Kencana Colliq Pujie Arung Pancana Toa, a Calalai who was a Bugis leader all the way back in colonial times who was in charge of handling monarchy documents and maintaining relations with figures like Stamford Raffles.

Though you can easily say that women now are given much more autonomy in terms of work, it is hard to ignore the stigmatisation they still face as well as the insane sense of insecurity many people feel in their own perception of gender, much of which feels performative.

As a heterosexual male-identifying person, I am extremely cognisant of the way Singaporean society is structured in a way that seeks to reinforce a sense of masculine identity, especially through state initiatives like compulsory military service. It is strange to see the sense of insecurity that can breed from this constant reinforcement, the ugliest thing being the sense of entitlement people feel to a relationship with someone of the opposite gender, largely stemming from peer pressure and a desire to prove their masculinity to others.

In this light, it becomes easier to understand how insecurity fuels the worst of male behaviour in this country, like the unacceptable string of sexual harassment cases in local universities. Calalai does make one wonder how drastically the Southeast Asian region has been shaped by western beliefs and values as a result of colonialism, and what our systems and perceptions of things like gender would look like without its influence. Especially what it would be like to live in a society as open, flexible and understanding as the Bugis.

As a whole, both Taboo and Calalai present two deeply thought provoking explorations of identity in two drastically different ways. Taboo presents a narrative shrouded with obfuscation, in many ways appealing to our interior and exterior psyche. On the surface appearing to be an exploration of the way our personal identity is controlled and restrained by outside forces, and on a deeper level through its haunting and surreal images, an acknowledgement of how terrifying and unknowable personal identity is.

Calalai on the other hand as a documentary presents itself with utmost clarity to create a sensitively captured ethnographic look at a society that has transcended traditional notions of gender, showing that identity is constantly shifting and a lot more fluid then most recognise.

Together, both films remind us that identity is a central question of existence that looms over much of human art, that there is a shared desire to understand who we are. As such they show that there is no one way to approach the subject and that there are a multitude of genres and techniques in which to examine it. Ultimately, there is value in observing something we can barely grasp and something immediately accessible, hopefully both can deepen an understanding of the lived experiences of others and enrich our understanding of ourselves.