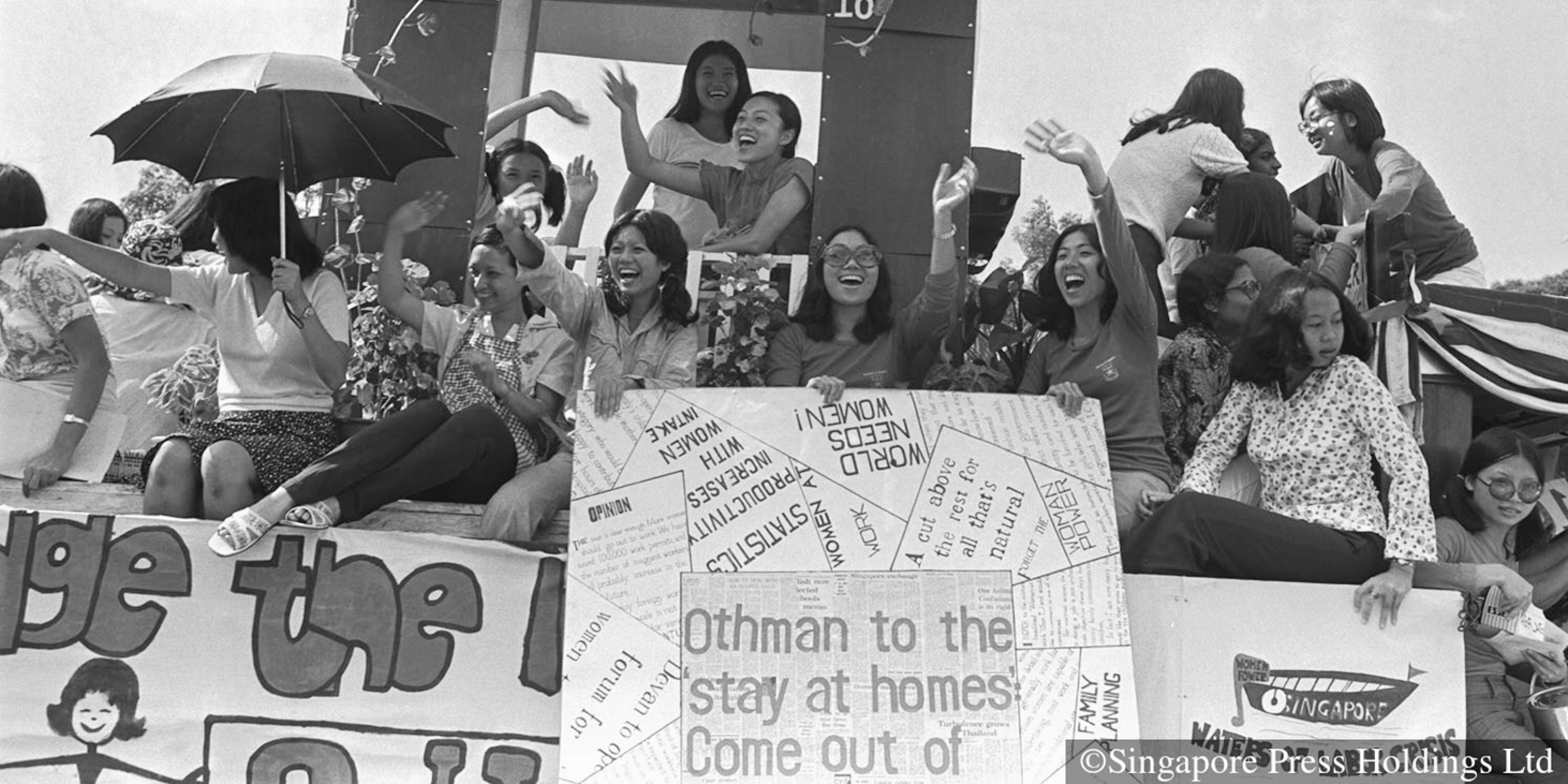

Top image: womensaction.sg/Singapore Press Holdings

This is the second piece in our series on How To Disagree Productively.

In the first instalment of our series on How To Disagree Productively, we spoke with Dr. Sara Delia Menon, who helps couples work through their differences in her practice as a therapist.

For our second piece, we thought we’d get a different take on the topic—specifically, in the context of advocating for social justice.

Conflict is inevitable in the process of trying to drive institutional or policy change, and influence public opinion. How does your approach to disagreement shift when, rather than helping people listen to each other, you’re trying to get them to listen to you?

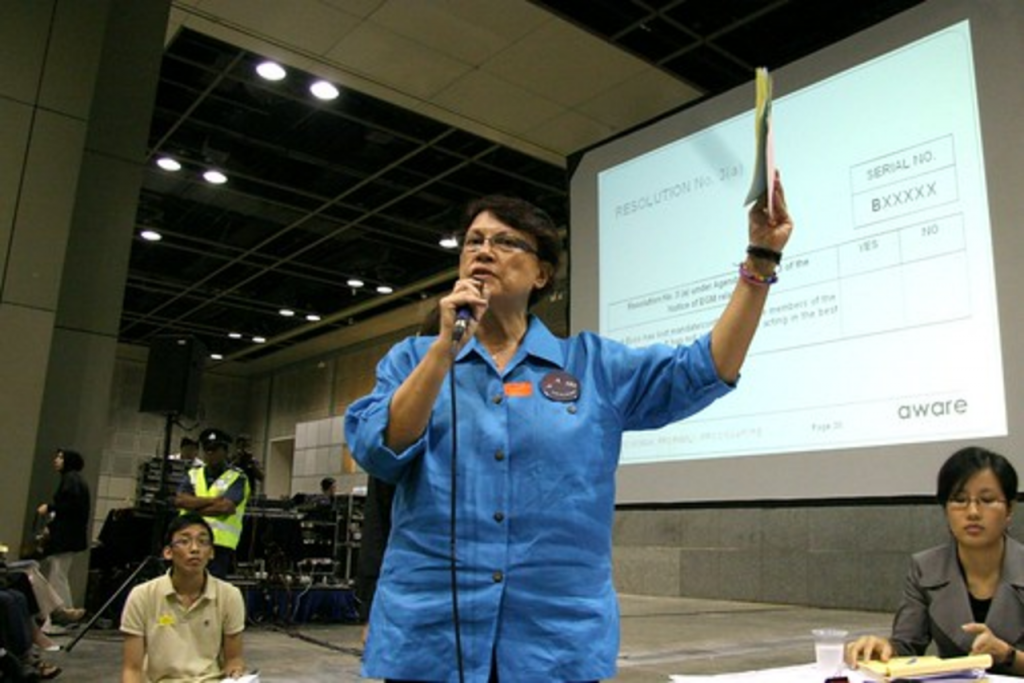

We spoke with Margaret ‘Margie’ Thomas, a long-time advocate, about her experiences with difficult conversations across 30 years of pushing for social change. A former journalist, Margie is the current President of AWARE and one of its founding members, as well as a founding member of TWC2. Her comments in this interview were made in her personal capacity.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Q: Could you start by explaining how you see advocacy? I’ve always imagined it’s fundamentally about changing minds—wanting to convince people, to get them to care about an issue; so, ultimately, to agree with you.

A: For me, advocacy starts when you see something you think is wrong—usually a social issue—and needs to be fixed in some way, which you approach either individually (e.g. by writing to your MP) or as part of a group.

There’re two audiences that you’re trying to reach: the public, and policymakers. You want them to see your point of view and agree with you, at least in part, if not in full, and then act on it.

Part of it is about trying to change specific laws and policies, or organisational practices. But you also want minds and perceptions to change, and I think that starts at home: family members listening to each other, classmates, colleagues.

Q: And I’m sure you end up butting heads with people in the process— people who, naturally, see things quite differently from you.

A: Yes. Fundamentally, persuading people is a challenge. It’s not easy.

One thing to recognise is that this takes time. For example, the campaign to change the law around marital rape took years. You have to accept that these differences will be around for a long time, and you have to be in it for the long haul. And sometimes, it’s a matter of recognising when you’ve run up against a wall and are just banging your head against it.

I wasn’t personally involved in this, but way back in the ‘80s or ‘90s, I remember activists like Dr. Kanwaljit Soin (former President of AWARE and Singapore’s first female NMP) managed to get a meeting with the then-Minister for Community Development to talk about an issue. Afterwards, they told me they’d found the Minister quite guarded and defensive and not very open to their ideas; they managed to get the meeting, which was great, but didn’t manage to make much progress. Same thing with working with the police on handling rape and sexual assault; again, I wasn’t directly involved in this, but it was very hard to make headway. The turning point really came when there was a police commissioner who was open to recognising that the issue needed attention.

It’s slow work. You sometimes have to wait till you have someone who’s sympathetic to what you have to say. And hopefully, that person has some power or influence in shaping the system.

Q: How much room do you see for trying to find ‘middle ground’ in the work that you do? Is that a helpful concept?

A: It depends. If your target is changing the law or a policy, then the end-point is simply when that law or policy is changed. But if it’s an issue rather than a specific goal, then I guess the first thing is to try and get conditions so you can talk openly about it.

Rather than talking about middle ground per se, I think it’s more helpful to start from asking how you can build trust and connections between people, so that you get to know each other, and don’t see each other as simply wanting to throw stones, but as people who also want the best for Singapore, and simply have different perspectives.

Q: So would you say it’s not so much about finding middle ground, but looking for common ground first?

A: Perhaps. Often, once you get to know policymakers at different levels, you realise that they’re making policy because they have similar concerns about the same issues you care about—poverty, inequality— but they have to work within their structures.

Advocates don’t necessarily have the answers either. Sometimes it’s just saying: here is a problem, here are some possible solutions, let’s try and keep the conversation going.

Q: Speaking of keeping a conversation going: do you believe in moderating your tone if it helps win someone over? Is that being strategic or simply sugarcoating?

A: I think it’s being strategic.

To give you an example, when AWARE was formed in the 1980s, civil society was a completely different place. People didn’t really speak up a lot. So when AWARE was registered and we had to appoint a President, we persuaded Lena Lim to do it. She wasn’t that keen, but she was the most ‘conventional’ amongst us.

We knew we would be seen as this bunch of bra-burning, angry women, and Lena was Chinese; mainstream; a mother of two; a business owner; middle-aged; as opposed to some of us who were academics, or had jobs which simply didn’t allow us to take the position. We made a choice to present a face that would be most acceptable. I think that’s just being strategic.

Q: What else have you learnt about concessions and compromise?

A: There’s the question of when’s the right time to raise an issue. For example, AWARE’s been doing work on migrant spouses for a while, but in the build-up to GE, or when xenophobic sentiment began rising and fears about whether foreigners are taking our jobs … valid as our concerns are, we did ask: is this a good time?

Again, I don’t really think it’s about middle ground per se, but recognising all the other obstacles and considerations that make discussion possible. If the ground isn’t right, or if the conditions aren’t right, to be having a conversation, then you wait for a better time. You need to know when to pick your battles.

Sometimes, if we’re coming up with a report which we feel we should do, but which we suspect the government might not be happy about, we do reviews before we go public. We share our findings with relevant officials, they give their feedback, and some of it makes sense because they point to things that we had no knowledge of.

This isn’t censorship or getting their permission; it’s discussing with people in the know to try and understand what the issues are. We might well adjust our recommendations in that case, because we know this is more productive. We’re ready to make adjustments if it makes our asks more reachable, but I don’t think this is exactly middle ground either.

Q: How do we ensure our own intellectual humility along the way? I think many of us struggle with the exact same thing we accuse others of: being convinced of our own rightness, without really asking ‘but what if I’m wrong?’ And close-mindedness and groupthink are problems no matter which side of the ideological spectrum you’re on.

A: So this is interesting; let’s go back to the founding of AWARE. We came together because we shared common interests—dare I say, common anger. But in our monthly meetings, we had a lot of arguments.

Of the 12 of us, we observed that maybe there were those amongst us who were more radical, the academics who were immersed in feminist theory. There were the older ones, who were more conservative, and those of us who were more middle-of-the-road. But we all recognised the value of having that kind of debate and diversity, and in the end, we could have all these arguments and friends at the end of it.

Q: This brings to mind the issue of infighting. I interviewed a rabbi a couple of years ago, and something he said has stuck with me ever since: that sometimes, the bitterest disagreements are between people who are already on the same side— between camps, rather than across the table.

I’ve always found this interesting, because it often feels like people often want the same things, and the disagreement is over how to get there, but those disagreements can be extremely heated and bitter. How do you manage this?

A: Honestly, it’s not easy. As an organisation, you want to present a united front, be it to the public or policymakers. But you are what you are, and I think the critical thing is to recognise that if you want to reach out to others, and find some way of keeping conversations going, we have to find some way of working together first.

The AWARE board is all volunteers, and at a basic level everyone should accept the organisation’s values, but we do try and ensure diversity. We might ask: do we have enough corporate types, so that we can work with organisations? If so, should we have a really strong feminist to be a check on the rest of us? Even within your own like-minded tribe, you can’t just go with the flow—you have to encourage difficult questions.

[Inter-organisational work] is also something I could be doing more of—trying to get people who are not ‘AWARE types’ to understand some of the things we do, and see if they can do it in their own ways.

Q: In your personal experience, what helps in making inroads, and creating this constructive space? Right now, it feels like we’re all screaming at each other, especially on the Internet.

A: Here in Singapore, I think we need to understand the value of argument, the need for dissenting views, and being prepared to agree to disagree. My personal feeling is that this needs to start from the top. As long as Ministers tend to deal with queries dismissively, or say, if you’re not with us, you’re against us, that’s going to be very difficult.

I’m not optimistic, but maybe after this GE, like with the decision to appoint a Leader of the Opposition, this somehow or other signals a new era in politics. Where in our highest policymaking purview, we welcome rigorous debate without letting it become personal.

The other side of it is that in schools, children should be helped to understand the value of difference: how to argue and debate, encourage independence of mind, and respect each other’s point of view.

Q: For sure. But true empathy is always so difficult; I wish I could say I’m capable of this, but I’m not sure how much I’d be able to engage with, say, a pickup artist. It’s a lot easier to be willing to listen when you sense that someone might already agree with you.

A: You’re right, and I don’t think we’re anywhere near to finding an answer. We could all use training in having difficult conversations!

It’s somewhat easier with policy, because you can identify the specific laws and policies you want to change and make recommendations. But changing minds and getting the message out is much harder. We have to live with the reality that we can’t reach everyone, but you can’t just preach to the converted.

Again, I don’t think it’s necessarily about middle ground, but there are different audiences, and different actors bring different things to the table. To get through to people who would never pay attention to things like toxic masculinity…maybe we also have to find other ways to present the issue, or working with other groups.

Q: What else helps in getting across to others?

A: Sometimes, one thing that comes up is saying that if you use feminism, you must recognise all these other terms and ‘isms’, but trouble is, once you use labels and terms, you sometimes end up being put in little boxes. I’m sympathetic to the view that language can sometimes alienate people.

I mean, in the early days, most of us hadn’t even read the typical feminist texts. I haven’t! I find them difficult to read, it’s just a bit too much for me. Of course you don’t have to read these texts to be a feminist. But I also recognise that academic approaches are important in giving people a structure for thinking about certain issues.

Take a slightly different example: Professor Teo Youyenn’s work. As an academic, she wrote about neoliberal morality, but she also felt a need to make her work relevant to ordinary people. So having produced her academic work, she also wrote a book that was accessible enough to sell 30 or 40,000 copies. She took the issue of inequality and made it something that even people who might not notice it felt a need to do something about it.

Q: We’ve talked a lot about approaches at an organisational level, but I wanted to ask about your personal experiences. You’ve had 30 years of disagreeing with a lot of people. Has it gotten easier over time, and what has helped?

A: Disagreement is inevitable in advocacy, but it’s not about being antagonistic. It’s the whole loving critics thing: we want a happy, healthy society as well. We’re not saying you’re doing a bad job, we just mean that you can do an even better job. And you have to recognise the changes that have been made over the years. If you compare the policymakers of 30 years ago with today, there is a difference.

I should also caveat that I wasn’t directly involved at the forefront of a lot of these fights! But when you recognise that something is wrong and you want to take a step to bringing about change, you realise that there is a lot of complexity.

You can’t just think, ‘this is wrong’ and expect it to be righted. You have to understand what’s led to it to be that way before you can slowly work at bringing about the change that’s needed.

There is a certain degree of compromise, but if you see compromise as finding the most effective way to talk, without necessarily weakening your argument, I think that’s fine.

Q: Incremental progress is better than no progress at all.

A: Only a child would expect complete agreement, or for things to happen immediately … if you really want to help your cause, you learn very quickly that you may need to change your tone. Scolding people doesn’t help. And you make the short-term compromises that you think would help long-term gain. But there are no textbook answers to these things.

You have to have stamina to keep at it and test it. If after 5 or 10 years, you still feel very strongly about it … but if you find your views changing, then maybe it was a losing fight. You’ve got to be very clear about what you want changed, and whether change is really needed.

At AWARE, we’re always asking ourselves if the things we’re calling for really resonate with the woman in the street. Do you have a right to assume that you know what she wants? You have to have those conversations with yourself all the time. Ideological purists may be talking out of sync with the real needs of people, but you also need the ideological approach to understand why certain things are this way, or why people don’t see the need for change.

Q: There is that tension there—you start from the assumption that what you’re saying is important, but you have to square that with validating (or invalidating) other people’s experiences.

A: Yes. A certain degree of humility is important. If you want other people to listen to you, you need to be ready to listen yourself, and see why they don’t see things your way.

Did this interview change your mind about anything? Send us your thoughts at community@ricemedia.co.