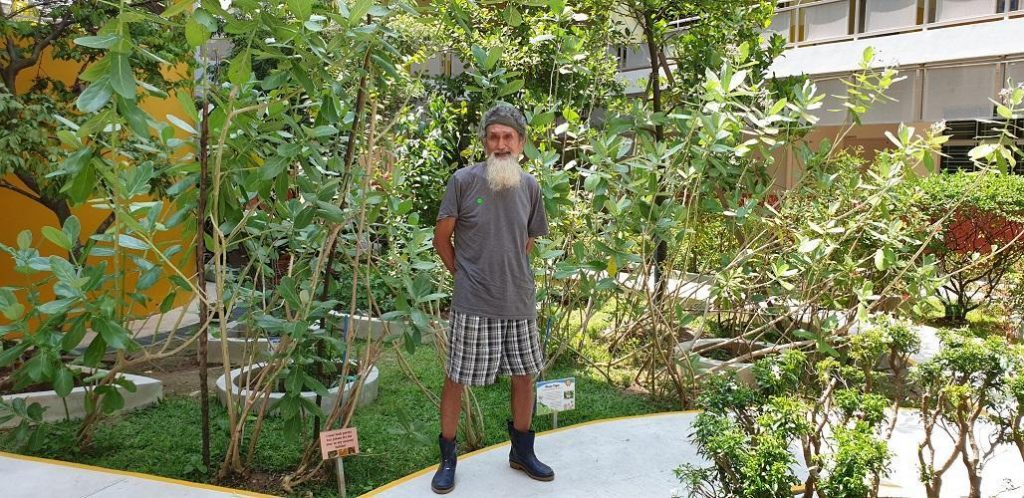

He explains that these evergreen plants, glowing brightly under the sun, attract butterflies that the children will hopefully be delighted to see.

“So are you anti- or pro- government?” he casually asks. I wonder if my answer might lead to a more restrained response on his part.

Nope. Moments later, he launches into a diatribe about the US and its facile commitment towards climate change. Shortly after, he berates Singaporeans for having the “attention span of an ant”.

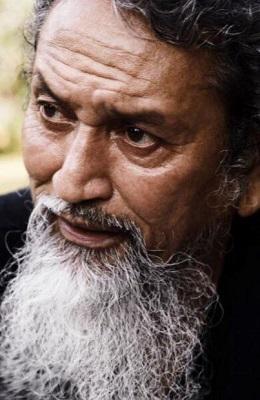

Indeed, this hardened 71-year-old environmentalist has done it all: from working with the native people of Malaysia and Thailand on forest restoration projects to tracking orangutans in the Borneo jungles. Locally, he’s also responsible for planting thousands of trees at the Singapore Botanical Gardens and Butterfly Garden.

Grant comes from a long line of pioneer environmentalists in Singapore. Inspired by seasoned conservationists such as Keith Hiller and Eric Alfred, he worked with notable folks such as Subaraj Rajathurai (a veteran conservationist who passed away in October 2019) and Professor Leo Tan (ex-chairman of Nparks and chairman of Garden City Fund).

Together, these men have been responsible for developing our national museums, protecting the biodiversity at Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserves, Labrador Natural Reserve, and organising educational tours.

But Grant is different from these established sorts. His character is bigger than the tally of his environmental endeavours, many of which sound like straight-up adventures in and of themselves. He draws respect because he doesn’t abide by facile norms. Although he doesn’t speak thunderously, he is often politically incorrect; his words acerbic. Profanity is not beneath him.

At the same time, there’s something introspective and expansive in his diagnosis of the Singaporean attitude to, well, everything.

He describes his sentiment at the time: “It was the age of dissent. Government was just smacking people down, dissenters like Tan Wah Piow. And we can see in London, with their own Speaker’s Corner at Hyde Park, people can bloody scream to kill the queen and government don’t give a shit. We need more constructive conversations here, you know, things like minimum wage or CPF transparency or POFMA. How can the government be judge, jury and executioner all at once?”

His grassroots tactics to address other social concerns can be characterised as not only creative but also persistent. Unhappy with the proliferation of more private golf courses, he sent an anti-golf postcard that quoted from Lee Kuan Yew’s words—“most good for most people”—to the Minister of Environment every week for years to advocate for common swimming pools and parks.

The tactic itself may seem laughable, but it was also apt. After all, not only the establishment can claim to honour LKY’s message; fringe actors like Grant are just as invested and want to hold their feet closer to the fire.

That streak of holding others accountable would also see him reporting the overcrowding of fish at the Sheng Shiong supermarkets and the rubbish overspilling at the Changi Village bus interchange on rainy days. The latter took more than 3 years to rectify.

Everywhere he goes, he has no qualms with speaking his mind to rectify moral lapses, even though he’s no intellectual. He’s no Thum Ping Tjin or M Ravi, and speaks in florid prose. But this doesn’t deter him.

All that counts for him is speaking up for yourself. And in so doing, his voice counted in effecting long-lasting change by introducing the idea of the Speaker’s Corner, which has snowballed into making other causes possible, like the long-running Pink Dot.

Like some Robin-Hood-esque sea pirate, Grant and his friends would sail out of Punggol in the wee hours of the night to find boats engaged in illegal longlining. They would daringly cut the nets of these long nets to sabotage their efforts, before escaping in into the night.

These were dangerous waters to swim in (pun intended) since he was afraid of getting caught. His eyes widen and his voice shakes, “If you get caught, you can get beaten up and nobody will know. But you know lah, we think we are doing the right thing and being self-righteous about it.”

Hence, his conscience always got the better of him, and he persisted until his boat gave way to wear and tear.

“Do you think this kind of spirit still exists today?” I ask, because this kind of gung-ho activism is obviously exceptional and not for the faint-hearted.

He guffaws and replies, “Impossible. Even my friends who used to do this don’t share the same passion as before.”

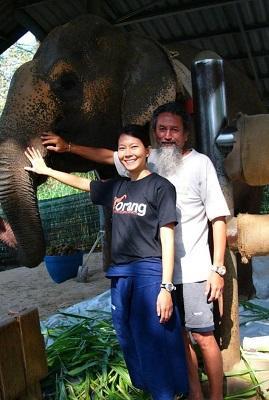

He clarifies that being an environmentalist is not about engaging in extreme tactics. As a Director of Reforestation for the “Save the Elephant Conservation” in Chiang Mai, his focus is on reforesting land areas for these elephants. The organisation stays afloat by depending on corporate donations and volunteers from around the world come to work with the elephants for short visits.

In a sorrowful tone, he describes how these elephants usually come to him in a terrible state.

“They are damaged with no commercial value because they have been used for breeding or tourist rides. Some even stepped on landmines. Our sanctuary is hook-free so we don’t hook them or offer rides. Every elephant has 1 mahoot (a Burmese helper) and they roam around freely.”

Looking through his photos, I am reminded of my own friends who visit Thailand for precisely these elephant sanctuaries.

Highlighting the importance of such interventions, he argues, “Some people say we should release them to the wild, I say what wild? There’s no more wild. When I am there, I have to reforest 87% of the land by bringing coffee saplings to the villagers and elephant poo as fertilisers. Like that, then the villagers are more open to the elephants roaming around these areas.”

Not all of us may be interested in working with elephants In Thailand. However, even if we are not capable of looking after these animals, we can broaden our understanding of how conservation works. By enriching our understanding of the multi-dimensions of any environmental issue, we can find pockets where our efforts do matter.

Having started it 25 years ago, he credits the effectiveness of having celebrities like Zoe Tay help communicate the message. Another success was the campaign against Resorts World Sentosa bringing dolphins and whale sharks to their aquarium. These campaigns demonstrate that the wider public does in fact have empathy for animal suffering, and most don’t want to exchange the lives of these animals for our palates or amusement.

On a smaller scale, with his “Green Volunteers”, Grant organises educational adventure group activities for the young. They travel to Pulau Ubin to study the forestry, bird-watch, and conduct clean-ups at mangroves at Sungei Api-Api.

Given his extensive time spent with the young, I ask him about the qualities and ingredients that have served us well, as well as the shortcomings.

This sets him off like a wild animal freed from its chains.

He opines: “The problem with the young is they rather be co-chairs than leaders. I get very tired of it sometimes, I ask them to be more proactive in something, they say, no lah I don’t want to lead. I think our youth suffer from these 3 Rs: Read, Remember and Regurgitate!”

That being said, Grant recognises these limitations. Describing the problem as the extinguishing flame of “idealism”, he elaborates, “Usually that idealism is there in their 20s, then as time goes, their lives change and they have families and careers, it gets harder for them.”

Sharing that his volunteer group consists of a diverse range of students, professionals as well as a Japanese family, he clarifies, “Don’t get me wrong, I have volunteers who have been with me for years, even if they can’t be with me physically, they can contribute in other ways, e.g. my doctor volunteers can pass me medicine that I can use in Thailand.”

It matters that the leader continues to draw support over a long period of time. Most of us have no idea who spearheaded the campaign to stop eating shark fins but here we are decades later with an impressive record.

To him, we seem to have lost the communitarian spirit that existed in the past. Observing how we currently live in a surveillance state, relying on CCTVs to spy on each other, he reminisces the days where “our doors will be open and the children around the neighbourhood will play with each other.”

He adds that the age of hyper-consumerism has desensitised us to the loss of Singapore’s biodiversity. He questions me, “Do you know that we are richer in terms of biodiversity compared to North America?”

Honestly, I had no idea. Strangely, I feel a swell of pride in my gut (for what? I didn’t do anything, right?).

“Yeah really, if you account for the different types of trees, fern, fungi, flowers and all these things. We don’t know how to appreciate what we got,” he answers.

When I ask if Singaporeans exhibit any intellectual curiosity during these tours, he chuckles, “The most common question I get is, this one can eat or not? I say, yea you eat one time, that will be your last time lah.”

Right. I’d like to think we are more than just a nation of gluttons looking for the next thing to eat.

If you are a millennial or younger, you’d have heard the common grouse that “we don’t appreciate our past” from boomers everywhere. But as I suggested earlier, I think that once we are reminded of the value of our heritage, many can’t help but feel compelled to protect or own it.

For instance, even if it doesn’t feel palpable, most Singaporeans are inclined to agree to “make personal sacrifices to help combat climate change” by “shifting to a low-carbon economy”, according to the National Climate Change Secretariat (NCCS) survey in 2019.

Or as seen with the Covid-19 pandemic, when crises such as the state of care for foreign workers jolts our collective conscience, we are capable of engaging in constructive conversation to demand change.

Grant points out how other countries have developed a greener vision, such as the Japanese educational system which incorporates a strong civic and environmental ethics module. Over the years, the Japanese have embodied a keener sense of environmental value, with even a public holiday called Greenery Day, established on 4th May to honour Emperor Hirohito’s love for plants and nature.

His suggested slogan: “Steam, Boil, No Oil!”

He explains, “For a campaign against the use of palm oil, it needs to be backed up by the system, meaning the Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Education. What I want to see is multiple efforts on all fronts, so like putting out information about the negative health effects of using palm oil, or modifying the home economics lessons to have healthier recipes. You need to have real ammo in this fight, and don’t forget, if we go against the palm oil industry, they are going to fight back hard. These are very rich people with deep pockets too.”

It is a thought-provoking proposition.

As I leave Yu Neng Primary School after our interview, I think about how Grant’s sinewy and weathered appearance obscures his “larger-than-life” role in Singapore’s history and development. Despite looking old and feeble, he continues to stick his hands into the dark soil, shovelling dirt and planting human-sized trees.

I was told that Grant Pereira is no Greta Thunberg. While this is true, this also speaks to the heart of the issue, doesn’t it? We have no Greta Thunbergs in Singapore (yet). But one Greta Thunberg will never change the world. If nobody had rallied behind her, she would have been passed off as another specimen of narcissistic Gen Z.

So is Grant Pereira’s message less deserving? Just because he is more radical, does it mean we can’t act on the essence of his message?

It is senseless to conclude that we all must be like him to do our part for the environment.

But we can speak up. We can be proactive.

As we face the ongoing crises that have been brought upon by climate change (and now Covid-19), the crucial question for us to address is: what are we inheriting?

I’d like to think we will answer it with a future as luminous as what I witnessed in Yu Neng’s school garden.