“Why is the Shiba-Inu’s tail curled down to cover its karcheng?”

“Why is the Shetland Sheepdog so aggressive?”

“Why does … ”

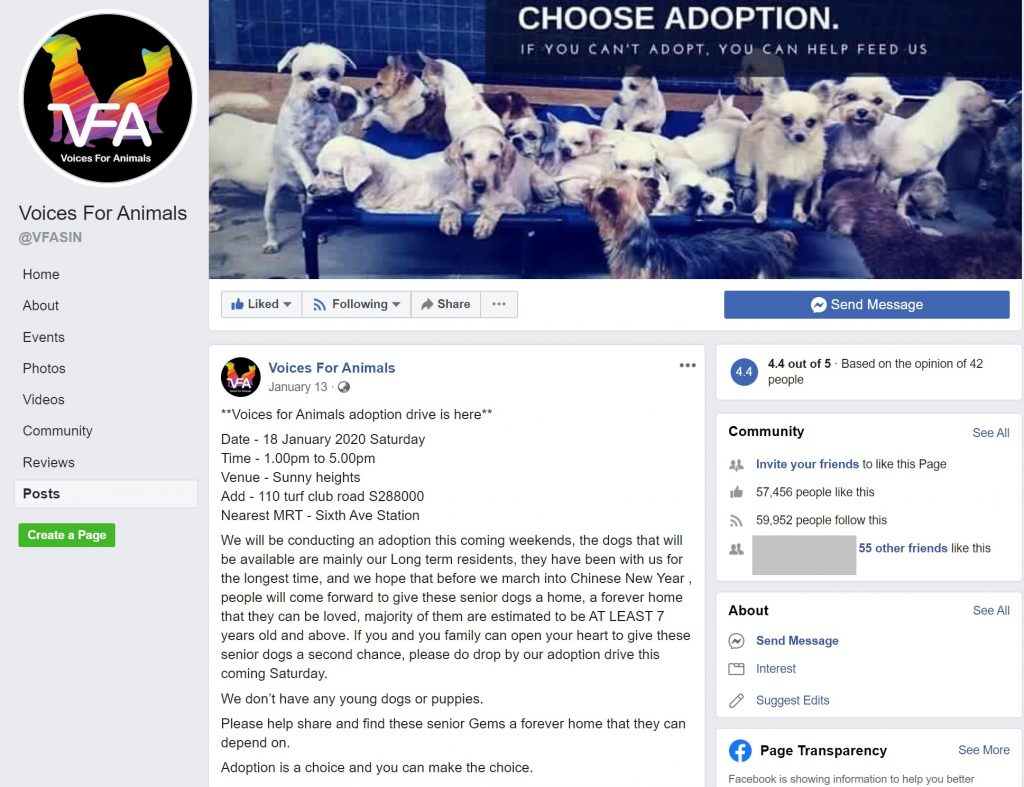

My six-year-old daughter would rattle these questions off whenever we visit adoption drives for rescued dogs—like the ones in January, organised by animal welfare groups (or shelters) Voices for Animals, Paws N Help Outreach, and Exclusively Mongrels.

On a near monthly basis, dogs are given away to these welfare groups for various reasons: owners moving out of condos into smaller HDB flats (thus failing to meet requirements for HDB-approved dogs), expats migrating overseas, or dog breeders giving them up because they’re no longer productive (aka “puppy mills”). For stray dogs, or “Singapore Specials”, they’re normally rescued from construction sites or streets, with the intent to be sterilised and rehomed.

Most purebred rescues released by breeders to shelters are aged 7 to 10 years old. They are usually females, passed on because they can no longer produce healthy litters of pups. If nobody wants them, their stay at a shelter can be indefinite (with the help of donations and volunteers). The adoption fee per rescue varies between S$100 to S$400, not counting medical costs.

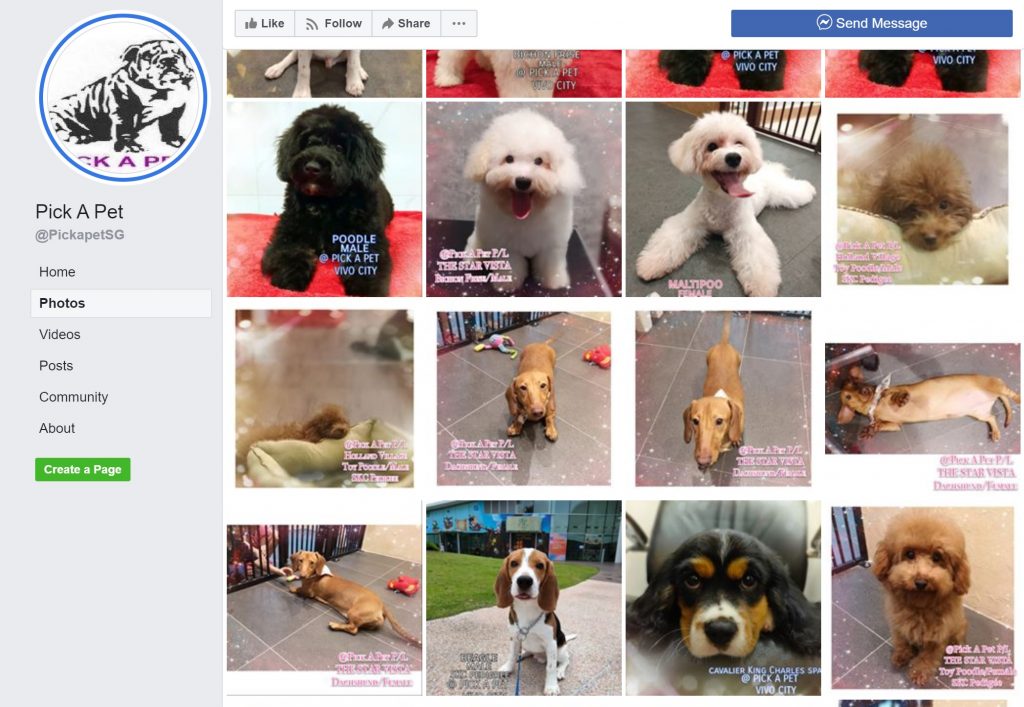

So as a father looking to buy a dog for his daughter, I have to make a financial and moral choice. Do I buy a S$3,000++ puppy with all the cuteness, interactivity and energy befitting of a six-year-old, knowing they can build a bond from the start? Or, do I adopt a seven-year-old rescue for S$300++?

If it’s the former, I might be feeding into the puppy mill industry, even if the breeder assures me the puppy was bred ‘ethically’—meaning the puppy’s parents are free-roaming, kumbaya-loving mutts (translated: they weren’t caged for the sole purpose of producing pup litters twice a year for profit). Remember, pet shops and farms have to pay license fees to AVS (Animal & Veterinary Services) to run their business. The ones who do not pay include illegal and unaccounted home/backyard breeders. So it’s big business, and it’s not restricted to just Singapore.

To help me make up my mind, I met with a friend of a friend—Karen, the owner of Gaia Wholistic Animal Wellness Centre, an animal rehab in Jalan Besar. There, she introduced me to a Corgi named Noah. Since his birth in 2018, Noah has hydrocephalus—a condition where cerebrospinal fluid builds up in his skull—“water in the brain”—resulting in brain damage on a cellular level. He suffers from side effects like partial blindness, motor discoordination and seizures. Every so often, he would rattle his head as if something’s not right. Puppies born with it are usually euthanised to avoid expensive surgery, but not Noah.

Before turning one, Noah underwent six surgeries. Imagine a two-month-old baby going in and out of hospital six times. One surgery involves the insertion of a shunt into his brain (through his nape), which comes with a manual valve. Through it, excess cerebrospinal fluid is expressed out and reinjected into his abdominal cavity (to be reabsorbed into the body). He was under general anaesthetic in 3 of the 6 surgeries and heavy sedation for two. Here’s one of the surgery videos (viewer discretion is advised).

Karen’s rehab centre has been treating many rescue cases like Noah, such as Max, a two-month-old Japanese Spitz. Max was almost put down by an ex-breeder because he was born with deformed hind legs. Similarly, he was the runt of a litter due to excessive in-breeding. He couldn’t walk, so he slides and glides around instead.

“My initial plan was to treat his emotional trauma. Like any human child, he would be comparing himself with others and become extremely defensive,” Karen said. “He barks often, trying to sound fierce, but it is a coping mechanism. Then comes the physical issues like malnutrition, poor blood circulation, cold exposure around his feet and low bone density. The rescue mum had to add calcium powder, massage his legs, administer warm-packs and do a lot of home exercises.”

“There are some registered breeders who do home breeding for show, agility and prestige dogs. Usually the ones with certification and come from good parental breeds. If you sell puppies from a farm, their parents are normally in a room, cage or kennel. For pedigree breeders, they do home breeding, litter by litter, and not rush the puppies for sale. They are more considerate by taking care of the parents. I personally cannot comment on the physical condition for both, whether it’s good or bad.

“But, there are also many unethical or unlicensed breeders in Singapore. It’s very difficult for the government agency, like AVS, to investigate. Singaporeans are like that. If there are no issues, then I’ll mind my own business. It’s just how we put up cases and choose not to voice out that much. It depends on the severity of the cases.

With pros and cons on both sides, it boils down to the emotional connection between owner and pet, regardless of where they’re from.

The bigger question I have to ask is whether we’re ready to bring a dog into our lives as if we’re having another child. Whether it’s a puppy or a rescue, the commitment is similar. Are we prepared if we’re frequent holiday travellers or rarely at home? Do we have the patience to train a puppy if it pees and poops all over our floor and furniture? If we adopt a rescue, are we prepared for any outcomes from its first veterinary check-up? Explaining this to my six-year-old is going to be tricky.

Throughout our visits to pet farms, kennels and adoption drives, all she cares about is having a dog, whether it’s a puppy or a rescue, in the hope that it will scrounge around our four-room apartment, jumping onto beds and couches, racing after the frisbee in the backyard or East Coast Park. My wife and I identify with her need for social attachment; she is our only child and gets lonely when we’re at work. Until we’re able to have a second child, a reciprocal, loving pet seems good in theory.

But personally, I need proof that the puppies I’m buying are ethically bred. I cannot, on my conscience, condone mills or inexperienced home breeders. Western Australia is introducing a bill to render puppy farms and pet shops illegal and improve traceability of dogs. Netherlands has zero stray dogs due to a mandatory and free sterilization programme that favours adoption. Hong Kong has introduced mandatory laws requiring hobby breeders to get licensed or face inspections. Just recently, Montreal and Laval in Canada made it compulsory for all dogs and cats six months and older to be microchipped and sterilised (unless there’s a medical reason or they’re licensed and approved for breeding).

In Singapore, all dogs are required to be microchipped and licensed for trackability, but sterilisation is not mandatory, so backyard breeding and puppy mills continue to thrive. A cursory check across local Gumtree ads, Facebook and WhatsApp groups will reveal the dark side of this business. There’s just no way to effectively police them (let alone find proof). The government should consider extreme measures like mandatory sterilisation as the next step. It can pass a law allowing AVS authorities and potential owners to check the genealogical track record of the puppy’s parents and view their living conditions.

If my family is lucky enough to qualify for a rescue pet, I need to be sure it’s still possible for my daughter to form an emotional connection with the rescue (I need to prepare for its medical bills).

For now, I’ll continue to work on convincing my daughter to settle for a guinea pig or a rabbit instead. Maybe she’ll warm up to the idea. Hopefully, when she’s old enough to distinguish the difference, the laws will have become kinder to dogs, and she won’t need to make a moral choice at all.