Day One: Pudong International Airport, Shanghai

20th January

If I had known the Wuhan Virus would turn into SARS 2.0, I would have stayed in Singapore for CNY. I love my grandma, but not enough to risk coughing my last in the No.1 People’s Hospital isolation ward. My grandma would concur—if she were not senile. She would slap me senseless if I had knowingly taken such risks—and for CNY of all things.

In my defence, the Wuhan virus was not even front-page news when I left. Now, 5 days later, POFMA seems about as important as the McDonald’s Prosperity Burger. When I landed at Pudong International Airport on the 20th of January, everything had seemed perfectly normal. The immigration officers were bare-faced. The thermal scanners idle. None of the passengers traveling home for CNY had even troubled to wear face masks. In the taxi, my driver talked not of the Wuhan virus, but of the 18 million who had left Shanghai to return home for CNY. I waited 6 hours for a fare! What bad business!

For what it’s worth, I regret returning. I repent I repent I repent.

Day Two and Three: Communist Youth League Guesthouse, Suzhou

21-22 January 2020

In the morning, I read about the one confirmed case in Shanghai. I was worried, but nobody else seemed even slightly concerned. Not my chauffeur. Not my uncle. Not the party officials who met me in Suzhou. They talked not of the growing crisis in Wuhan (300 cases), but of economic development in the region, party politics, internal affairs, the higher mathematics of sucking up to Beijing.

It was only in the evening when I felt the first inklings of something serious stirring. I had been invited to dine with a director in some State-owned Construction Company vaguely involved in Singapore. The dinner was cancelled. All party officials summoned for ‘emergency meetings’.

Day Four: French Concession, Shanghai

23 January

I awoke from uneasy dreams to find a very different city outside my window. The big news on WeChat: Wuhan is off-limits. No one goes in or out, whether by air, train, or car. The word used by the western media is ‘travel ban’. Chinese social media calls it ‘Feng Cheng’—i.e. Sealed city. Judging by the pictures, just then emerging, of empty train stations, desolate supermarket shelves, and police checkpoints, I would say that Chinese social media had chosen the more apt term.

Outside, on the streets of Shanghai, the news seems to have taken immediate effect. Half the people on the streets are wearing Face Masks. In the city centre, it’s more like 90%. Blue Surgical masks. Black rubber masks with disposable filters. Perky N95 masks with respirators. It adds some colour to the normally drab winter fashion. The sea of olive and khaki and black now broken up by patches of white and blue, as the masked men quickly begin to outnumber the bare-faced.

No one talks about anything but the ‘Wuhan Virus’, now re-baptised as the ‘New-type Pneumonic Coronavirus’. One woman laments the lack of hand sanitiser. They were sold out in the three pharmacies she had visited this morning. Another whispers to her friend that there are probably more cases than the government lets on. Round every corner, in every overheard conversation, at every red light, there is nothing but virus virus virus. The fear is so thick, I could butter my bread with it.

In Watsons, an elderly uncle is shouting at the service staff, spittle flying as he waves a packet of black foam masks in their faces, shouting: “Will these masks stop viruses? Will it stop the Wuhan Pneumonia?” The staff shrug their shoulders, so he asks again, louder and more insistent, until the older one is forced to reply: “We really don’t know, how can we know?”

He storms off without buying. She scans my lip balm (I already have a small arsenal of masks) and says to no one in particular: “How can I take responsibility for something like that? What if something actually happens?” I give my best half-smile of fake sympathy. Just glad that masks and soap are still available, panic-buying has not yet started.

At the Shanghai Museum in People’s Square, a female police officer checks my NRIC and my temperature with a handheld infrared scanner. She is flanked by the 4 military police officers in dress uniform (green with yellow stripe), ready to subdue anyone who tries to resist. Outside, three ambulances are waiting. Under such circumstances, my interest in Ming-Dynasty Furniture is rather lukewarm and I leave after an hour of strolling. The crowd is sparse and no one has removed their masks despite the sweltering temperatures inside. Exiting through the gift shop, I find one of the police officers warning the staff not to let anyone in through the backdoor. Even if they just want to buy a keychain. All entrants must have their temperature screened.

The hospitals have likewise sprung into action. Outside, there are bold red signs in supermassive font directing anyone with a temperature of above 37 degrees to the ‘Fever Triage’. Their effectiveness remains to be seen. The Ruiguang Hospital in the French Concession has a special area to separate potential coronavirus victims from other patients. In the Xinhua hospital (a famous paediatric hospital in Shanghai), this fever triage is an expo booth located beside the entrance, next to the main lobby where children are waiting for their asthma appointments and the elderly for their diabetes medication. There are only six applicants queuing at the booth, which is a relief.

At dinner, my cousin saunters in, wearing an N95 mask and carrying an infrared thermometer he bought from Taobao (77 yuan). He brings me more masks, and a piece of disturbing gossip which would later prove contentious: there are busloads of Wuhan natives who had fled the province. Since Shanghai is within road trip distance, and home to China’s best medical care, many have apparently arrived here, bringing the virus with them.

“We should tell them to get lost. They are not welcome here,” my cousin comments.

I’m reluctant to believe him, but it’s harder to dismiss the pictures of cars queuing for petrol. Where would they be going, if not out? Is this fake news or real? What would I do if I were in their predicament? After a long day fraught with anxiety, I drift off to sleep at 11. I dream about my grandmother dying of pneumonia.

Day Five: Reunion Dinner, Yangpu District, Shanghai

24 January

There’s an argument to be made for castrating middle-aged Chinese men. They are truly the bane of the earth, these uncles who continue to cough and spit and sneeze as if their bodily fluids were god’s gift to the planet. They were hacking when I left Shanghai in 1997. 22 years later, they’re still happily dredging up thick gobbles of yellow phlegm with that hhngggnnnnhhh noise and spitting it on the ground, into nearby bushes and against walls stained yellow by years of accumulated expectorate. This coronavirus epidemic has not deterred them. Perhaps nothing short of the death penalty will.

The city centre is quiet, but in the xiao qu—the residential neighbourhoods which are the equivalent of Singapore’s HDB estates—people are still going about their business. The shops are still open. The markets still crowded with people buying groceries for their reunion dinner. The mood, however, is subdued. There is none of the usual noise and yelling and bonhomie. People keep to themselves, moving hurriedly. No one stops to exchange the customary ‘Xin Nian Kuai Le’. No one shoots the breeze with their shopping trolleys in tow. Rather worryingly, none of the small-time shopkeepers are wearing masks.

The news in Shanghai continues to worsen. There is a doubling of confirmed cases from 9 to 20, and not all of them had traveled to Wuhan. In the meantime, China State Construction Engineering has received its marching orders. They are to build a 1000-bed lazaretto in Wuhan modelled after the XiaoTangshan hospital which—back in 2003—had housed all of SARS patients in Beijing. Shanghai has likewise dispatched 3 teams of doctors to aid the beleaguered medical services in Wuhan.

More are likely to join them. Across China, doctors and nurses have been recalled to duty. In Yunnan, my aunt, a haematologist by training and the head of the epidemiological control unit, is unable to return for reunion dinner. She doesn’t even have time to take a call from her granddad, who has to spend CNY alone, because—for better or for worse—both of his daughters are doctors.

Come evening, I sit down for the most sombre Reunion dinner ever. Things were never so dour, even when my grandfather lost his sight and his mind. After a few pleasantries about my job and Singapore, the topic swerves onto the only thing on anyone’s mind: The Coronavirus.

The anti-Wuhan sentiment is visceral. Over shrimp and scallops, I hear more morbid (unconfirmed) tales about the 300,000 who’ve fled Wuhan. One story claims they are holidaying in Shanghai Disneyland, waiting for the fever to subside and only seeking medical treatment after they’re bored of Space Mountain. Another unconfirmed rumour claims that Wuhan’s residential neighbourhoods are under martial law, with mandatory temperature checks at every entrance. Wait, isn’t travel out of Wuhan restricted, I asked. My uncles scoff at my naivete.

They can control the cities, but who’s to stop those living in the countryside from getting in their vans and driving clean across the country? My cousin of the aforementioned infrared thermometer swoops in with a story about his colleague from Wuhan: “We tried to brainwash him into staying in Shanghai, he refused to listen. Now he’s never going to get out.”

My mother, who is not entirely pleased to hear such talk at CNY, tries to steer the conversation towards more pleasant topics—like my nephew’s schooling or the rising cost of fruit. Each time, her efforts fail because disinformation and rumour travels so quickly and nobody can help clicking and sharing and getting swept along. The compulsion is like picking at a scab. Since nobody can do anything practical about the outbreak, we give ourselves the illusion of control by talking about it.

Halfway through the soup, my aunt receives a WeChat DM, Tiangling New Village in Shanghai has apparently been quarantined after the appearance of a new case. Over dessert, another message arrives. Our downstairs neighbour comes huffing and puffing up the stairs with her dog. After offering a perfunctory happy CNY, she offers another unconfirmed report: The Crowne Plaza near Wujiaochang is being disinfected after a guest has taken ill. It sends a chill down our spines. Wujiaochang is the same distance from my hotel as Yishun is from Toa Payoh, but the epidemic seems to have shrunk the city. Every case, however distant, feels like spitting distance.

Such is the depth of the paranoia that has gripped the nation. It is fed by a constant drip of ‘news’ from social media. Pictures of an empty Wuhan. Selfies in overcrowded hospitals. Masked police officers guarding ominous buildings cordoned off by tape. In the absence of reliable, first-hand journalism from Wuhan, all that anyone has are bits and pieces shot on smartphones. One viral image shows a man stuffed into a white box as he leaves the airport:

Another shows an overcrowded hospital in Wuhan with the caption: “What is this!? Just one Coronavirus case would doom all of us.”:

Yet another, soon to go viral, shows a sign which reads: ‘Visiting relatives is harming them, reunion dinners are certain death’

No one can verify any of it, but they circulate without context or explanation, leaving netizens to draw their own conclusions and thus fanning the fear. However, there is no news quite so dire as the message conveyed in the Spring Festival Gala—the after-dinner state-sponsored CCTV variety show watched—and loathed—by almost everyone in China. In a last-minute segment addressing the nation, the hosts implore—implore—Wuhan citizens to stay put and to avoid leaving their home.

“Our bodies might be apart, but our hearts are always with you,” cries one particularly mawkish host.

So it’s true, we think, people are indeed fleeing the province. My cousin suggests tracking them—a la The Dark Knight—by their cellphones/WeChat accounts and detain them. My uncle mutters darkly that it must some kind of American plot. We all agree that’s enough depressing talk for an evening. Everyone leaves by 9.

Day Six & Seven: The End

25-26 January

Normally, the population of Shanghai during Chinese New Year resembles a cos-x curve. It dips dramatically before CNY as people return to their families in other provinces, reaching its lowest point on New Year’s Eve, before recovering quickly when the visitors/holidaymakers come swarming in for the Golden Week holiday. The busiest day of the year is the second day of CNY. The first day is for sleeping late. The second, for visiting relatives and friends.

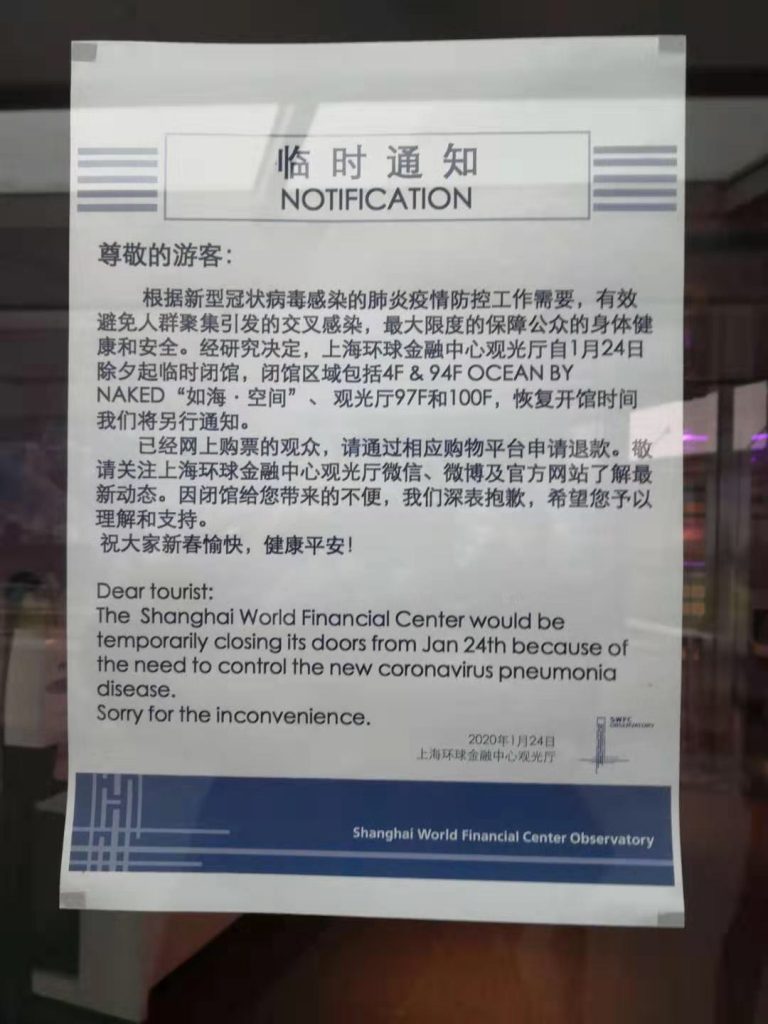

This year, the people left but the tourists and visitors did not come. The city is a ‘Kong Cheng’— an empty city. The museums, the cinemas and all public attractions—Shanghai Disneyland included—have closed ‘until further notice’. Outside Shanghai’s tallest building, Shanghai Tower, a young American backpacker yells ‘fuck’ as he realises the observation deck has been shuttered ‘indefinitely’. Also closed are the massive state-run bookshops and other institutions under government control. Directives from on high, no doubt. The malls and F&B businesses are still open, but there are so few customers they look pitiful. On the streets outside, Shanghai resembles Switzerland: I’ve never seen the place so empty and so quiet. The narrow streets thronging with pedestrians have suddenly turned into wide boulevards. The train stations look like cathedrals without their usual crowds.

In the trains, I lie down on the seats and listen to a balding Texan tell his Chinese girlfriend: “I’m telling ya, the real number is 90,000.”

In the taxi, my driver raves and rants behind his surgical mask. He oscillates between desire for personal safety and the need to make ends meet. Like the service staff in Watsons, he is speaking to no one in particular, but he wants the government to tell the taxi companies to lower their vehicle rates because there are no customers to be had and no money to be made.

“Yesterday, I picked up a wai di ren who arrived that day and decided to leave on the next because everything—everything—is closed,” he recounts, “What are we supposed to do when there’s nowhere to have fun?”

His anguish reaches a fever pitch as we speed past The Bund. Under normal circumstances, it would be impossible to cross because it is the most crowded embankment in the world. Today, it is a cemetery. We traverse its length in about 5 minutes flat whilst my driver shakes his head irritably and complains: “What a terrible situation. Very terrible indeed.”

Not that I’m complaining—given the circumstances. The number of confirmed cases has increased from 33 to 40. 1 critically ill. 1 deceased. Not great. Not terrible. News from Wuhan, however, gets worse and worse. 12 other cities in Hubei province have been sealed off, and a second XiaoTang Shan is to be constructed to accommodate the ever-growing cases.

That’s all I have to say. With no one left on the streets and no more dramatic developments, I can only offer a few opinions on Beijing’s handling of the crisis. It is all personal prejudice, so I beg your forgiveness.

For once, the stars are aligned. For once, the western media and China’s state-run media are in agreement about the cause of the crisis. The New York Times laments—rather predictably—about China’s lack of open-ness and the government’s secrecy. The Global Times—which has supplanted The People’s Daily as the central government’s leading mouthpiece—concurs. In a widely-read editorial, it blames the Wuhan government for its attitude of ‘nei ji wai song’ (internal panic, external harmony). This sounds like arcane gibberish, but it essentially faults the leadership in Wuhan for downplaying the epidemic publicly, whilst working feverishly behind the scenes to contain its spread.

They should have raised the alarm sooner, instead of keeping it under wraps for fear of repercussions. In short, they should have done what the NYT columnists advised. The only difference is, the Chinese media has blamed Wuhan whilst NYT, Foreign Policy, and the usual suspects have blamed ‘China’.

This is a valid criticism, but it’s also a fairly predictable one. It is the same op-ed from 2003, recycled.

Personally, I think this corona-crisis is as much a product of bureaucracy and hierarchy as it is the offspring of opaque-ness and secrecy. Since every decision has to go up and down the food chain several times before getting the right sign-off from the right committee chairman—essential action is always and necessarily delayed. Once the approval arrives from the very top, the work is carried swiftly. Public spaces are shuttered with remarkable promptness. Gallons of disinfectant are found to bleach and scrub the trains. However, in the absence of instructions from above, there is little initiative or vigilance in the lower echelons, who are too silo-ed to even notice the chaos until it comes knocking on the doors with one bony hand.

In Suzhou, for example, nobody raised an eyebrow at the mounting death toll in Wuhan. No one even mentioned the word ‘virus’. Along the canals and in the scenic water towns, people strolled, drank tea, and bought kitschy souvenirs. There wasn’t a thermometer or a face mask in sight. Meanwhile, at Tencent, my cousin reports that temperature screenings had begun more than 10 days before CNY.

No doubt there are some apparatchiks who wanted to be the fever police, but lacked the authority or the approval.

More importantly, however, is the deficiencies and inequalities in China’s healthcare system. I mean this not as a criticism of the doctors, but of the state. It is an open secret that China’s medical system is overtaxed. Even in Shanghai, the hospitals are often overcrowded, and one’s access to medical care is often dependent on connections, wealth, and privilege. The best hospitals—301 in Beijing, Huadong in Shanghai—are reserved for senior party officials. Unless you can pull some strings or make the right call, security will remove you from the A&E.

The situation in Wuhan, a city of some 11 million people, is probably no different. It cannot cope with the massive influx of patients, much less the whims of those who—understandably—want the best medical care available for their loved ones.

Hence, the scenes of chaos and panic in Wuhan. Hence, the construction of not one, but two temporary hospitals. Hence, the people fleeing the province—they doubt if they will get the best possible treatment, they fear they wouldn’t get any treatment at all. Under such circumstances of doubt and mistrust, who wouldn’t make a run for it?

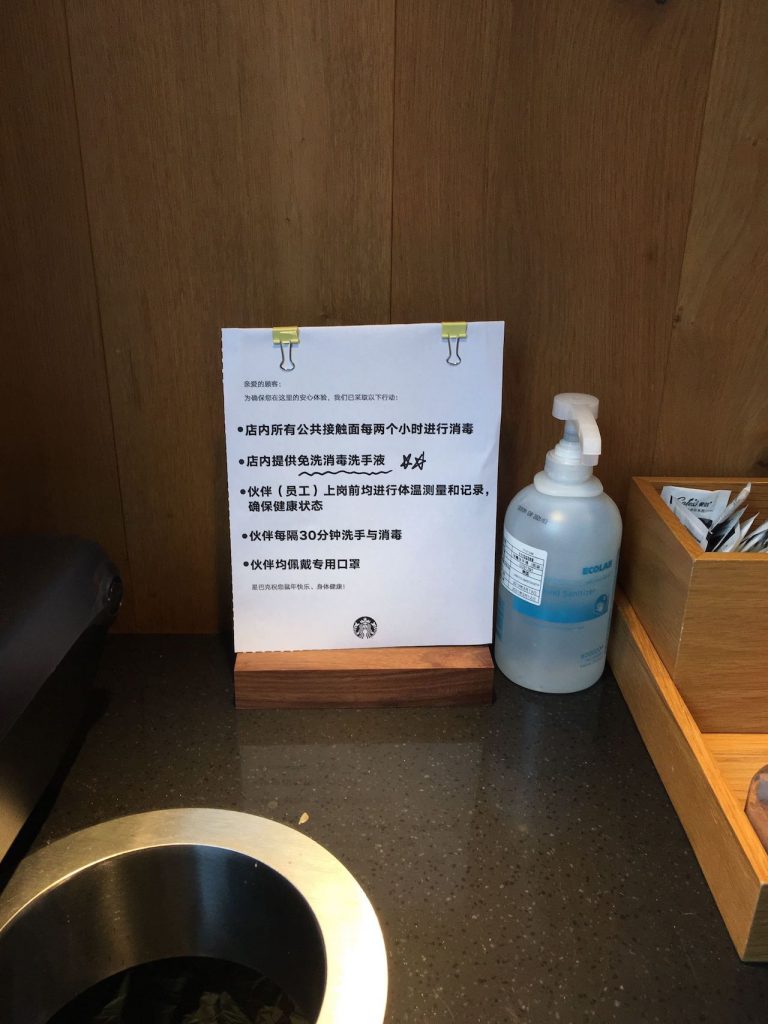

But I’m getting ahead of myself. For now, Shanghai is quiet, uncertain, waiting for the storm to pass. Things have the appearance of being under control. The numbers, which have doubled every day since 21st January like clockwork, have slowed their merciless upward trajectory. Despite a laggardly start, the state is doing everything it possibly can. Notifications about hand-washing and mask-wearing have been plastered on social media, in train stations, and in hotel lobbies. Every LED screen, big or small, has been commandeered to spread the gospel about hand-washing and mouth-covering.

As for me, I’m trapped in my hotel room. There is nothing to do but to read, smoke, and wait. I venture outside once a day for fresh air and Starbucks, not daring to linger on that one-in-a-million chance of infection. It’s pretty irrational and paranoid, I’ll admit, but all sanity has long since fled.

One fearful family friend has purchased a VPN to read the ‘real’ news from BBC. Another has cancelled a holiday to Japan because her two young children won’t abide by face masks. Outside, the city looks almost peaceful, but looks are deceiving. Beneath thick winter coats, everyone is anxiously fidgeting with their phones, waiting—just waiting—for more bad news; the next death, the latest mishap, another doctor infected despite the full precautions.

Until then, there’s nothing to do but to wash your hands, and pray.

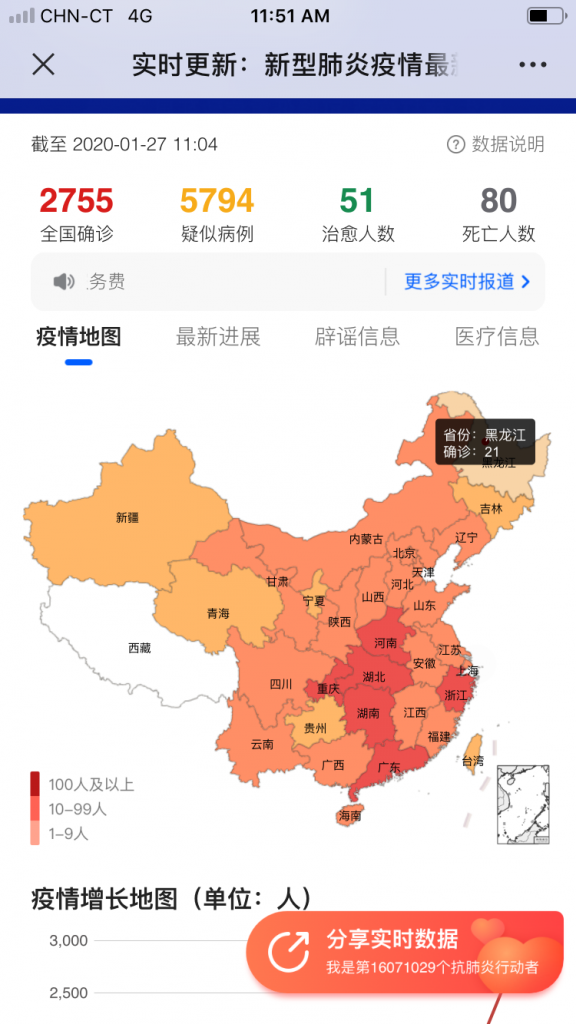

Total confirmed cases: 2755

Total suspected cases: 5794

Successful treatment: 51

Total deaths: 80

Have something to say about this story? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co.