“It’s so funny to see you speaking Mandarin,” my ex-colleague quipped.

I explained to her that I was fluent in mandarin because I am in fact bi-racial—Chinese on my paternal side, and Indian on my maternal side.

“Oh, so you’re just ‘half’ then,” she mused.

She may or may not have realised it, but underlying the phrasing of her statement was her belief that I’m not really Chinese, and by implied meaning, that I‘m not really Indian either. In my experience, being bi-racial—to many Singaporeans—is about being both but, oftentimes, also neither.

For most of the 33 years of my life, I have needed to answer a question that strikes at the very core of a person’s identity: “What are you?”. With time I have realised that this seemingly innocuous question really stems from a societal need for monoracial people to understand how to classify multi-racial or bi-racial persons, and therefore know where they stand in relation to us, and how to interact with us based on the perceived racial group they assign to us (usually subconsciously).

When we think of Singaporeans, we tend to think in terms of Chinese, Malay, or Indian persons (myself included). ‘Others’ (at best) is a vague minority group of everyone else and (at worst) can feel like a subsidiary/fringe group within a national identity. To experience a greater sense of identity and function well within Singapore society, bi-racial persons frequently feel the need to make a choice socially (and to a lesser degree, publicly) on which monoracial group they want to be seen as identifying with.

Unfortunately, this is an illusion of choice. Most bi-racial persons you meet in Singapore will affirm that the ‘choice’ is often defined by everyone else except themselves.

He looked at me in surprise and said, “Oh I’m not racist! I just have a preference.”

Confused and upset, I asked my mother what he meant. I can’t recall what she said to me at that instance, but I recall that she gave the driver an earful, and in her heart, it must have hurt.

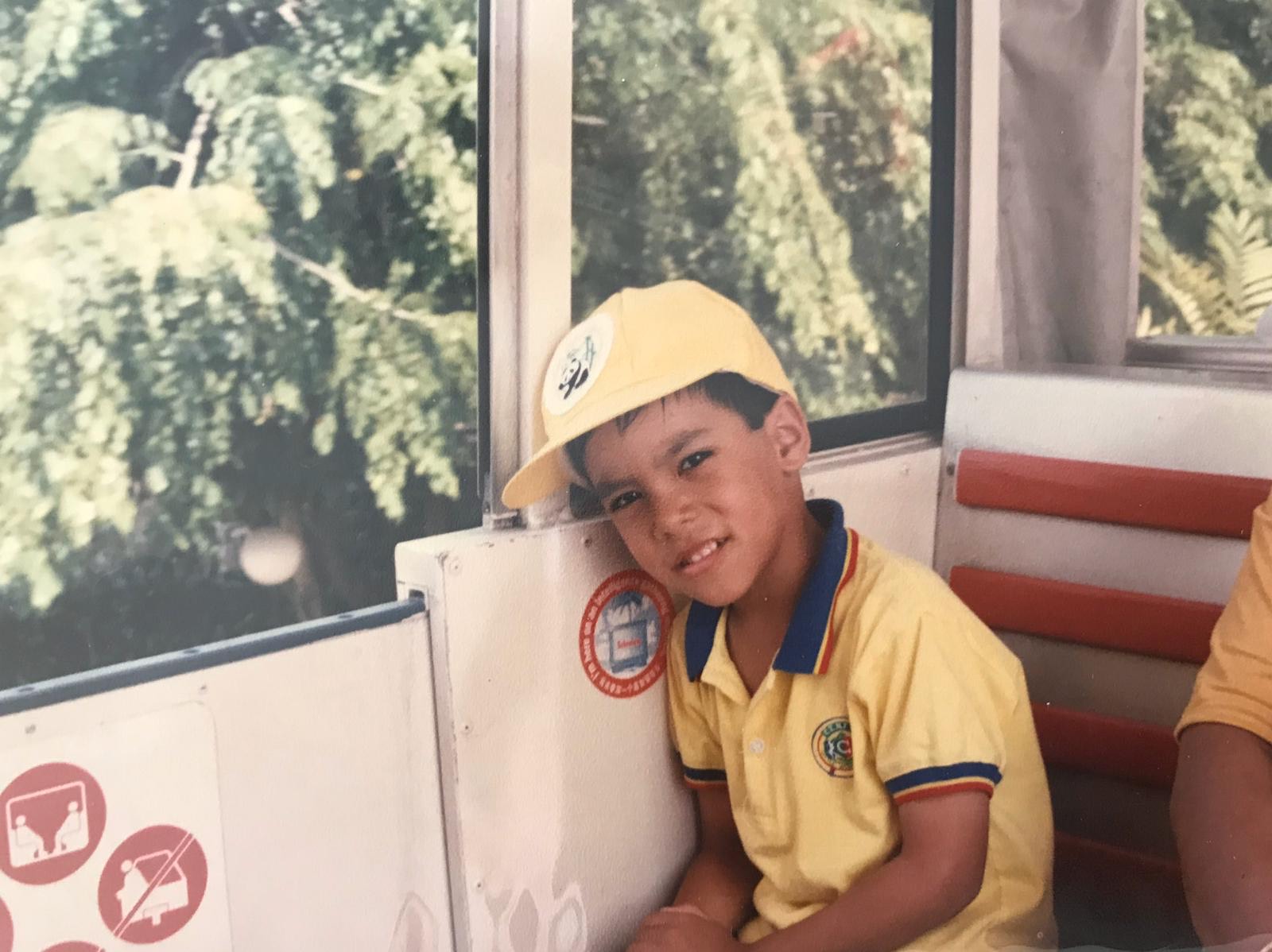

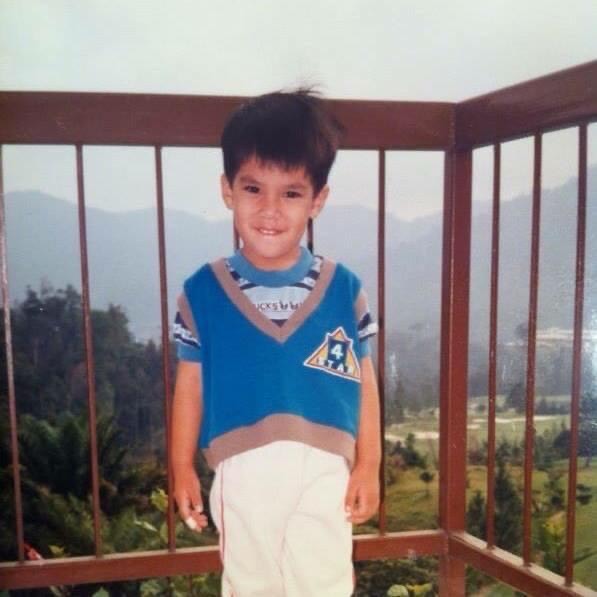

When I decided to write this article, I wanted to hear her thoughts, and started by explaining the gist of this story. Immediately, she mentioned, “The bus uncle.” I was surprised that 28 years on, this was her instinctive recollection, especially since we’ve never spoken about it at length. She told me that I was very upset when I went to her, and she felt that the driver had created doubt in me about my identity (in particular as a Chinese child). Today, however, she recognises that the driver had no malicious intent, but simply had a myopic or limited worldview. She feels that bi-racial children are common in Singapore today, and probably better understood, although interracial couples still have to deal with some level of stigma.

As I got older, the questions and comments became more pointed. Sometimes, it was insensitive: Why are you not ‘black’ if you are Indian? Why did your parents decide to get married? Oh mixed means you are Eurasian.

And the worst one: “You look good for a half-Indian guy” (why wouldn’t/shouldn’t I look good?).

During Mandarin lessons, teachers would either look at me sceptically (in spite of me having a Chinese name and surname) or overcompensate by giving me additional attention for being bi-racial, the assumption being that I would need additional support in learning the language. Any good score I achieved in the language was looked on with incredulity by my classmates (a classmate said examiners went easy on me because I was mixed), and made me feel like it was expected I would be sub-par in my competency, and culturally inferior simply because I was mixed.

Being of both the majority and minority race (but mostly identifying publicly as Chinese in my earlier years), I always felt the need to emphasise the Indian half of me in later years—almost as though to add legitimacy and wholeness to me as a person (because I can’t be half a person right?).

Once, a close Chinese friend remarked to me, “I wouldn’t date an Indian person”.

After reeling from the shock of having that said to my face, I responded that it was in my view, a racist attitude. He looked at me in surprise and said, “Oh I’m not racist! I just have a preference.”

When I then reminded him that I was Indian and what he had said was offensive to me, he said, “Oh no not you, I meant like, actual Indian people.”

As an adult, I have realised that one of the views sometimes from monoracial minority groups is that bi-racial people aren’t really a minority group because we can ‘race-switch’; we are able to identify and de-identify with whichever racial group depending on what is more advantageous in that circumstance. While there is some truth to this (and I have been guilty of exploiting it—deliberately appearing more ‘Chinese’ because I live in Singapore), we forget that for many bi-racial people who look physically monoracial one way or another, this is not an option that is easily exercised.

As a society, we still put bi-racial people in boxes based on how they present externally, and we are not really interested in according them their biological identity—and, by extension, their cultural identity and identity of self. To the status quo, you are still largely one or the other, and being equally both is not comprehensible. Being asked, “Do you feel more Chinese or Indian?” (as if one should matter more than the other) supports my point.

Most bi-racial persons you meet in Singapore will affirm that the ‘choice’ is often defined by everyone else except themselves.

My hope in sharing my story is that more bi-racial people who are seeking racial clarity will realise that this a common feeling among our folk. And that even if we are subject to classification by the society we live in, our persistent decision to self-identify as both racial groups is ultimately what will move the needle for the generation after ours.

If we are to actively participate in national conversations around race and privilege, we must first be comfortable with the question, “What are we?”