All other images by the author unless otherwise stated.

Just don’t wear black. In early October that was the pre-arrival instruction I received from friends enmeshed in that modern urban war zone, Hong Kong.

“Don’t worry, you can wear black, nobody will think you are a protestor,” rebutted Tang, the jovial cabby in his fifties who picked me up from the airport, gesturing at my brown skin. But for Cantonese locals like him, wardrobe options have indeed become limited.

Black for protestors. White for their opponents. Red for China. Blue for the police, i.e. those alleged to have tortured some “blacks”. “Also no pink, no green,” Tang joked, lest he be mistaken for a homosexual or a bleeding-heart environmentalist.

“So I wear yellow. Yellow is safe.”

Tang rattled off other jokes—“Where is the most dangerous place in Hong Kong? The police station”—while glancing at his smartphone, which beamed a digital buffet of protest updates, video clips, cabby chatter, and yes, even the occasional phone call. Tang’s calmness, coupled with the quiet on the roads, put my mind at ease.

A few traffic jams and subway closures aside, the next week would prove one of the smoothest and most enjoyable I’ve had in twenty-five years of visiting Hong Kong. I discovered new nooks, traipsing around the lush Sai Kung pier in the northeast, alongside hikers and tourists from China and the West, and slurping up beef tendon noodles draped in a rich restorative broth, in a Cantonese joint near the Aberdeen Centre in the far south, not a word of English exchanged.

The dramatic television scenes of petrol bombs, shattered storefronts, and masked protestors clashing with police seemed a world apart from my visitor’s bubble.

This year the generational divide has narrowed. “We will be gone in thirty years,” said Tang. “They have to fight for their future.”

This includes his daughter, who has just graduated from university in Savannah, Georgia. She had wanted to return to be with her friends after seeing the million-person demonstration this past June against a proposed extradition bill, the spark for this year’s protests.

“I said sure. But you pay for yourself [her air ticket]. Is that fair or not?” he asked me rhetorically. “Fair right?”

Alongside this acceptance of youthful idealism is a more sober expectation of short-to-medium-term economic pain. “Yes, business has dropped, some days maybe fifteen to twenty per cent less,” Tang admitted. “But then there are no more mainlanders around. So am I happy or sad? Hahaha.”

It has become commonplace in multicultural societies around the world for older immigrants to cast scornful eyes at prospective ones, for instance with second-generation Indian Americans supportive of Trumpian border control. It is one of the many bizarre symptoms of a world in which liberal ideas of nationhood and identity are being seriously challenged by nativist ones, against the backdrop of yawning economic inequalities.

Nowhere is this impulse stronger than among Hong Kongers, who have turned sharply against the land of their ancestors, less than an hour’s drive away. The prejudice can be vile, expressed in physical attacks and slurs like “cockroaches”.

Indeed, some of the fiercest Sinophobia one might experience around the world occurs in two of its richest Chinese-majority territories: Hong Kong and Singapore.

The cities’ differences and similarities offer a prism through which to better understand their relative fortunes, as well as the impact of global capitalism on Asia.

Which Chinese-majority, East-meets-West, Asian Tiger city-state do you prefer: Hong Kong or Singapore? Over the past few decades each person’s answer to that has fluctuated in tandem with China’s emergence onto the world stage.

Right before “the handover” to China in 1997, many Hong Kongers left for Singapore, my birthplace, fearful of an uncertain Communist future and lured by Singapore’s immigration policy that gives preferences to ethnic Chinese.

(Ethnic Chinese comprise over 90% of Hong Kong’s 7.4m population and over 70% of Singapore’s 5.6m. Most of the former trace their lineage to Guangdong; most of the latter to neighbouring Fujian.)

By the mid 2000s, the mood had shifted dramatically. Hong Kong was brimming with confidence, its economy buoyed by a rising China, which was fast shedding its communist skin to reveal capitalist blood. The “one country two systems” philosophy underpinned (what seemed like) a vibrant cosmopolitanism. Locals, eager to ascend the property ladder, were no longer looking to switch cities.

Some foreigners were. “Hong Kong in your twenties, Singapore in your thirties.” Party hard in the city that never sleeps, and then settle down in the one where your children always will. Yet “Hong Kong vs Singapore” was always a sort of casual schoolyard bickering, nerdy Asian exam rivalry actualised at a city level.

Yet over the past decade it has been clear that the pendulum is swinging back to Singapore. Hong Kong’s property prices have continued to spiral—doubling in real terms from 2010 to 2018—making it difficult today for the young to even get on the ladder. Meanwhile locals have felt even more disenfranchised by Beijing’s increasing control over the city, itself symptomatic of the centralisation of power under China’s leader Xi Jinping, who assumed office in 2012.

This coincides with important milestones on the road to this year’s conflict: the 2012 protests against the proposed mandatory National Education course and the 2014 demonstrations triggered by electoral reforms that would enable China to decide which candidates could stand in the 2017 election to be Hong Kong’s chief executive (won by soon-to-be-replaced Carrie Lam, whose utter incompetence in office is the only truth that unites the city).

Coupled with China’s other apparent attempts to undermine Hong Kong’s autonomy, including the extrajudicial arrest and detention of five booksellers in 2015, it has become clear to many Hong Kongers, even before this year’s mooted extradition bill, that their leaders can never be fully responsive and accountable to them—rather, only to their overlords in Beijing.

This volatile atmosphere has been inflamed by communalism, spawned by an existential tussle over Hong Kong’s identity. The blackest Hong Kongers are content to watch their city burn, for theirs is a noble cause, one for future generations. And the reddest Chinese are happy to watch Hong Kong burn, ridding it of its British colonial hangovers and bastard children.

“Are you a Hong Konger or a Chinese?”

“Why not both?”

“Why MUST both?”

This is the intractable identity repartee of our times. In the tea room at my former office in Tai Koo Shing, three middle-aged female colleagues frown, bursting our long-time-no-see bubble, when I tell them I might soon be seeing Joshua Wong, one of the protest leaders, speak at a conference.

“Not all of us agree with what they are doing,” one says. “But we keep quiet. Otherwise [others will say that] we are not real Hong Kong people.”

Yet there is little tension in the air, rather a sort of grudging acceptance of an interminable battle ahead.

Tiananmen redux? Bah. In 1989 an insecure China fretted about Western eyes gazing in. Today the West fears losing Chinese eyeballs looking out. A growl from Beijing has seen the world’s most highly-paid and fearsome athletes kowtow. Le Bron may be the king, but we now know where the emperor at.

China, in other words, is acutely aware of the numerous market levers it now possesses, its ability to slowly suck the air out of Hong Kongers and their sympathisers abroad. Who needs tanks?

Faced with the seemingly unbridgeable divide between the protestors’ demands and Beijing’s space for compromise, investors, people, businesses and money are fleeing Hong Kong with newfound fervour.

Singapore is again benefiting (some US$4bn was transferred in the past few months). But ironically these very inflows might ratchet up the same incipient pressures—gross inequality; a property market tilted towards the elite; a dwindling of trust in political processes; and a tension between minor and major identities—that have cumulatively pushed Hong Kong into the abyss.

Are the tensions of one global city simply being channelled onto another?

To understand why this yo-yoing between Hong Kong and Singapore occurs, consider that geographically, historically and economically they have much in common. In the first half of the nineteenth century the British developed both as colonial port cities with extremely open economies. As vital nodes in global transportation networks, people, goods and money have long flowed freely through them.

Hong Kong’s and Singapore’s wealth and importance to the world grew under the British Empire. As administrative, financial and trading hubs, they were the manicured fronts that sheltered their inhabitants from exploitation near and far. This partly explains the relatively romantic view of colonialism and the West still prevalent in both cities.

Over the past fifty-odd years their economies have moved in sync rapidly up the industrial ladder, from textiles and electronics manufacturing to services. They have served as reference points for East Asia’s remarkable economic transformation, the leading edge of a supersonic jet, with per capita incomes growing over twenty fold since 1975. Today both are rich global cities with large financial services sectors and some of the world’s worst inequalities.

This is partly a symptom of them being the only global cities without obvious (domestic) hinterlands. So, on the one hand, they welcome huge inflows of capital and talent which, while spurring dynamism, also raises the cost of living and exacerbates inequality. On the other hand, there is nowhere for lower-income citizens to trade down to. Unlike New York City, Hong Kong and Singapore have no New Jersey.

Everybody is stuck in the same pressure cooker. Moving to neighbouring mainland China or Malaysia, respectively, as politicians routinely recommend, is for many an unconscionable option, an ejection from one’s own soil to a foreign land with weaker rule of law and temperamental locals.

To mitigate these innate tensions, the political and business elite in Hong Kong and Singapore have long tempered their liberal economic instincts with some more socialist policies, including in public healthcare, education and pensions.

Widening inequality is rationalised by the preservation of minimum standards: it does not matter how many Lamborghinis race down the streets, as long as the workers can afford jeans while being glued to their smartphones.

Ordinary Hong Kongers believe they are at the mercy of a triumvirate of real estate players—a land-owning oligarchy that controls many prime parcels, particularly in the verdant New Territories; developers unafraid to bid up prices; and a local government dependent on land sales revenues—that has benefited from the property bubble.

(One of the many delicious ironies surrounding this year’s events is that Hong Kong might be pining for the sort of land reform that market-oriented mainland China has long outgrown.)

Many Singaporeans, meanwhile, may come to believe that their own government—like in Hong Kong, the biggest landowner—has misled their investment decisions. Since independence in 1965 the government has sold public housing with restricted 99-year leases, repeatedly promising, in the words of Lee Kuan Yew, the first prime minister, that their value “will never go down”.

Most assumed the government would reacquire them at fair value. Only recently, following Lee’s death, has it flip-flopped to confirm what some feared: the properties will be worth nothing at the end of their leases. (At which point the government can redevelop the land.)

Put another way, for almost ninety per cent of Singapore’s population, their largest assets and nest eggs, some worth over S$1m (US$740,000), will start to shrink relentlessly to zero at some point during their (or their heirs’) lifetimes.

By contrast those in the upper ten odd per cent, including most politicians and senior civil servants, have wisely purchased freehold homes, many now worth tens of millions of dollars. Their assets will presumably keep appreciating long after their descendants have inherited them (with no estate duties). Singapore appears to have created an intergenerational time bomb of Pikketyan proportions.

High immigration has been necessary, politicians argue, because Hong Kong and Singapore both have one of the world’s lowest fertility rates, at 1.2 births per woman (well below the replacement level of 2.1). With one of the world’s highest migration rates, over the past thirty years Singapore’s population has doubled. Native-born Singaporeans are now well in the minority.

In 2014 Singapore’s former chief planner suggested an ideal population of 10 million. It may not be long before the hoi polloi are forced into Hong Kong-style shoeboxes. (Currently Singapore’s smallest unit is 258 square feet, thirty per cent larger than Hong Kong’s.)

In order to manage these numerous contradictions, both cities have relied on political models that offer their citizenry limited rights, but in opposite ways. Singapore has electoral democracy, in the form of regular elections, but none of the other substantive pillars present in liberal democracies, such as a free press, freedom of association and a vibrant civil society. Hong Kongers, by contrast, have minimal electoral rights but enjoy all those other facets of a free society. The Economist recently labelled Hong Kong a liberal autocracy; and Singapore an illiberal democracy.

This is more than a cute aphorism for policy wonks. It explains the differing political pressure valves in both societies. This is why Hong Kongers have long taken to the streets to voice their displeasure with their representatives, including the leftist riots of 1967, which ultimately led to social reforms under the British; and why Singaporeans, conversely, have an aversion to public protests, knowing they have the power, even if rarely exercised, to punish the ruling People’s Action Party at the ballot box.

Hong Kongers, in other words, are on their toes every day, watching vigilantly for government overbearingness or corruption. Singaporeans keep their heads down, store up any angst, and tally a mental report card once every few years before voting. Between elections Singaporeans, some of the world’s richest and most educated people, display a stunning degree of apathy toward civic and democratic participation.

There is a connection between their respective political identities and the vigour today with which Hong Kongers and Singaporeans assert their respective cultural identities.

Possibly the most stirring exhibition of Hong Kong’s resurgent local identity occurs ever so often around lunchtime in shopping malls. Crowds press up against the glass barricades overlooking an atrium, like theatre-goers split across multiple levels, to sing Glory to Hong Kong, a new Cantonese song that has quickly become a quasi national anthem (since few sing China’s official Mandarin national anthem).

Malls, oddly, offer an acoustic experience not unlike the echoey splendour of old churches. At Festival Walk in Kowloon Tong, I watched people emerging from a session energised, like devotees who had just received their daily manna.

“The ultimate emblem of capitalism converted into a Hong Kong identity shrine,” noted Rubio Chan, a former Hong Kong civil servant whom I first met during the 2014 Umbrella Movement. Despite all the short-term problems the city is facing now, Chan believes that the togetherness, the sense of belonging, “the Hong Kong spirit” is arguably stronger than at any point since 1841, when the British arrived.

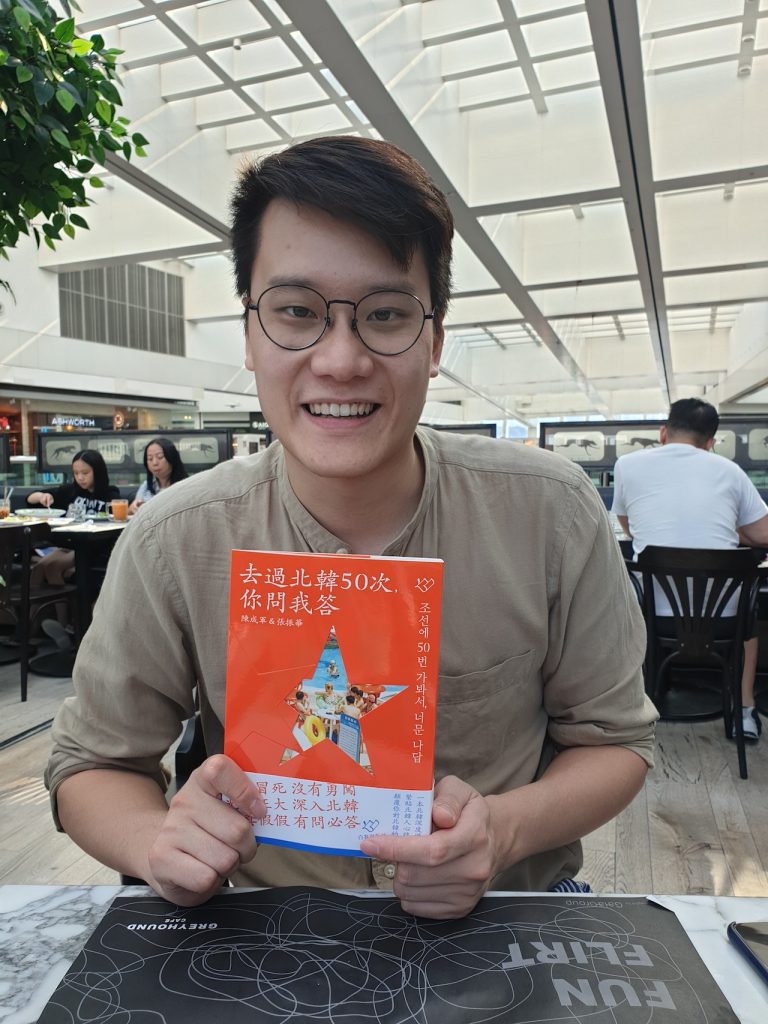

Over the past few years, as Hong Kongers have become more politically active and aware, their interest in other socio-political models has increased, he says. To tap into this, Chan co-founded GLO Travel, a specialised travel agency that takes Hong Kongers on unorthodox “socio-political” type travel, including trips to Iran, where they listen to discussions on Islam and Zoroastrianism, and North Korea, about which he has co-authored a book and filmed a travel show.

But when Hong Kongers visit North Korea, Chan says, it is one of the few times they shed their Hong Kong identity, and unashamedly boast about their Chinese identity, celebrating their blood-ties to the superpower that props up the hermit kingdom.

Some will find it reassuring that beneath all the waffly trappings of identity ensnaring Hong Kongers, a strain of Chinese pragmatism still burns strong.

Singaporeans are much friendlier than Hong Kongers, say visitors. We smile, we speak in (better) English, we very rarely snap in Cantonese—or any Asian language—with disdain.

Yet that also reflects the progressive de-Asianisation of Singaporeans over the past five decades, as we have been turned into identity-thin globalists. English and Mandarin, the lubricants of the globalised economy, have been prioritised over all else, including Chinese dialects; Singlish, our creole; and Malay, the language of our neighbours and geographic ancestors. Mother tongues and “ethnic” dresses have become party tricks for public holidays.

When Singaporeans sing Majulah Singapura (Onward Singapore), our Malay national anthem, it is arguably the most mindless demonstration of nationalism in the world today. Five decades on, perhaps three-quarters of Singaporeans still mispronounce their anthem’s words, its meaning lost on them. In sharp contrast to the visceral connection Hong Kongers feel to every word of Glory to Hong Kong, Singaporeans unconsciously parrot Majulah Singapura.

The ill-defined Singapore identity is at best a random assortment of public slogans, from hard work to multiculturalism, and at worst a bare, pragmatic, transactional idea, one about safe streets, low tax rates, and a passport offering unrivalled access to other countries.

In a world riven by identity politics, some might cheer this evisceration of deep ethnic culture, this evolution of pragmatic homo economicus. The Singaporean is, in many ways, a creature moulded to plug neatly into the borderless, soulless, profit-seeking multinational juggernaut.

The surprise to many in Singapore has been that the Hong Kongers—how dare they!—have had the temerity to promote cultural and linguistic nationalism, to try to forge a more local identity. Hai ah, hai ah. You’re meant to be materialists in a global city ruled by Mandarin speakers. Forget Cantonese already.

“Do you think what’s happening in Hong Kong will ever happen in Singapore?” asked an Indian American fund manager who had relocated his family to Singapore several years ago, one of the footloose global elite.

Unlikely, I told him. We do not have a similar sense of communal Singaporean identity.

He was relieved. I felt some regret.

Hong Kong and Singapore have grown and evolved in concert with the diktats of a globalised economy. While many are tempted to view recent events in Hong Kong purely through the lens of China, it may make more sense to see it as a warning light for unfettered capitalism and globalisation.

For decades the leaders of Hong Kong and Singapore, infused with a neoliberal fervour that might make Reagan blush, have courted multinationals and foreign investors with successive generations of tax holidays and ever-lower tax rates, with promises of easy immigration, with the delivery of essential services like international schools and cheap maids for the “Hong Kong in your twenties, Singapore in your thirties” set of expatriates on a global tour. (Some argue that this is essentially an extension of the structures put in place by the colonial East India Company.)

Any negative impacts on local society have long been downplayed. Darwinian meritocracies coupled with a still-persistent belief in trickle-down economics have ensured that successful locals sneer at those left out, those who “failed” at life. The dwindling of shared spaces means that each person’s experience of the global city differs greatly, the rich insulated from the poor by their chauffeured limousines and guarded country clubs.

“My world is very small,” said a protestor in August. “It consists of Tin Shui Wai and occasional trips to Mongkok and Causeway Bay. I don’t even know the convention centre or Kowloon Bay. This is my home.” This clinical segmentation of life is why privileged visitors like myself can still breeze through Hong Kong unscathed, picking at siu ngor fan, roast goose rice, at leisure while ignoring how the plate came to be.

But one thing Hong Kong this year has proved is that we cannot simply expect the proletariat to hum along in a stressful existence with the bare minimum, coupled with an increasingly small chance of social mobility, and with little say in how they are governed. The age of robots is not yet here.

What all this also means is that the real autocratic impulses facing Hong Kong and, to a lesser extent, Singapore, may not always emanate from local leaders but the arbitrage-and-profit-seeking corporations and the market-oriented ideologies to which they subscribe.

It makes, for instance, Singapore-style high immigration defensible. Consider the vicious cycle: low resident fertility has prompted politicians, drunk on the elixir of GDP growth and chivvied by MNCs threatening to leave, to welcome ever more immigrants; wage and population pressures have in turn forced residents into smaller apartments, further dampening their ability and desire to conceive; making migration even more crucial for the needs of global capitalism.

The very MNCs that depend on harmonious inter-ethnic workplaces are the ones, through their incessant demands on governments for more migrant labour, that unwittingly foster nativism and ethnic strife within “global cities”. In Singapore middle-class professionals from India are the current target of vitriol from locals.

(To be clear, this is not a critique of migration per se, which at a sustainable level is not just economically expedient and socially palatable but morally right.)

One observes the same corporate pressure, implicit or explicit, when it comes to tax rates, labour rights, and much else. This is a world increasingly dominated by technology giants who, more than any other corporate form prior, seem to view humans as replaceable digits.

Thirty years ago it was the sneaker sweatshops of Indonesia. Today it is the service sweatshops all around Hong Kong and Singapore.

Many in Singapore doubt if our Randian leaders, seduced by plutocrats in hoodies, can harness the technology sector’s promise while tempering its excesses. It’s no surprise that the world’s cryptocurrency merchants have made a beeline for Singapore.

The day after I met Joshua Wong I got into a cab with a thirty-five year old driver whom I will call Li. I spent two minutes trying to tell him about my meeting with “Joshua Wong”. He did not recognise the name, and I wondered if he was feigning ignorance because he did not want to be associated with the protestors.

I showed him my wefie with Wong.

“That’s Wong Chi-Fung! That’s Wong Chi-Fung! How did you get to meet him? You must be a journalist, right?”

Joshua Wong or Wong Chi-Fung? Even the name of a protest leader exposes the linguistic divide. I was the outsider looking in.

Li was amazed at how “cheap” apartments in Singapore are. He lives with his parents in a one-bedroom apartment that is worth HK$6.5 million (US$830,000). He cannot afford to move out and, with his fourteen-hour days, has neither the time nor money to date.

He asked about my favourite cities in China. I named a few: Chengdu, Qingdao, Xi’an.

“Oh Xi’an! Many different people there.”

“Yes, a bit like Hong Kong.”

“There are a lot of Muslims there. I know because they are the cheapest brides. You can get one for ten thousand Hong Kong dollars [US$1,280].”

In that one statement I felt a condensation of so many contemporary Chinese themes: urban anomie; the pragmatism of love and marriage; the preference for some kinds of Muslims (e.g. Xi’an’s Hui) over others (e.g. the Uyghurs); and even the occasional unity of the Chinese sub-continent, stitched together through social media and other modern networks. (Xi’an is over 1,400km from Hong Kong.)

Li and his parents could live decadently if they sold their flat and moved to any number of Chinese provinces. Unsurprisingly they choose to stay in the only city they’ve ever known. As such, their inflated paper wealth is a meaningless statistic.

Yet barring some major crisis in China, we all know where their story will lead. Come 2047 Hong Kong’s (apparent) benefits under the “One country, two systems” will expire. It will likely reintegrate with the Chinese mainland, perhaps as just another city in the planned “Greater Bay Area”, what is shaping up to be the largest conurbation in human history, with already well over 100m inhabitants.

As Hong Kong moves grudgingly but inexorably closer to China, Singapore continues to float gently away from its Malayan roots, as it makes connections to territories and people far away. This is why Hong Kongers are feeling the desperate urge to solidify their hyper-local Cantonese identity; while Singaporeans are comfortable being led by the itinerant, indiscriminating flows of global capitalism and culture (never mind the symbolic nationalism).

Nativist vs globalist is a gross simplification of the complex identity tensions many societies are facing. Yet the fates of Hong Kong and Singapore may offer clues to this thorny issue. Which society will be more successful? Which happier?

And, most importantly, in which would you rather live?