I am an ‘average’ Singaporean. I’ve lived in Ang Mo Kio for 20-plus years, in an upgraded 3-room flat, 15 minutes from the closest MRT. Rain or shine, I spend 90% of my time in flip-flops, much to the dismay of friends and employers. My corridor has played host to a procession of dying plants and speaking of foliage, I learned how to pronounce ‘Lettuce’ by standing in line at Subway. Before the arrival of the Footlong, I called it ‘Let-Use’ instead of ‘let-terse’—as did most of my friends, who spoke English in varying shades of broken.

In short, I am a true-blue Heartland Singaporean—or so I believed—until a friend disabused me of the notion: How can you be a Heartlander when you’ve studied overseas and now live in a Condo?

Past behaviour be damned, I was no longer one of ‘The Tribe’. I had joined the condo-dwelling caste with their German-made sedans and further-away holidays.

And I don’t even know how to drive.

George & Sumiko

This was a completely pointless conversation, but it did raise an interesting question: What the fuck is a heartland, really?

These days, the term ‘heartland’ is used so often that we cease to register its strangeness. Every time a Minister gives a speech about the ‘heartland’ at some ‘grassroots event’, we roll our eyes and zone out.

NDP mobile columns don’t visit Tampines or the East, they visit ‘the heartland’. In ST headlines, we speak of heartland SMEs, newly-opened heartland malls, and even heartland condos. When sex workers are arrested for plying their trade, we write editorials on how vice has penetrated the heartlands, as if Geylang/Orchard Towers were 400 kilometres away instead of $14 by Grab.

Nonetheless, the concept is universally understood. Unbidden, it conjures up images of a wage-earning, middle-income Singaporean who commutes to work by MRT from his/her home in Toa Payoh or Tampines, returning every evening to their family with a packet of something from the nearby hawker centre.

Sounds about right?

Well, it shouldn’t. There is no reason why this particular vision should be christened ‘heartland’. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word ‘heartland’ means:

1.The inner part of a country, region or area, esp in contrast or when regarded as important or powerful

2.A region which is especially important to or is associated with an activity, organization or ideology

Neither of these definitions makes sense in the local context.

Firstly, Singapore is too small to have an ‘inner part’. Secondly, I can’t imagine in what way is Ang Mo Kio or Yishun ‘especially important’ or to what ends.

The Ruhr valley is often called Germany’s ‘industrial heartland’ because of the steel and coal it produces. In Singapore, however, the term comes with no preamble. HDB estates are not the heartland of anything, they’re simply ‘the heartland’.

As it turns out, the idea of a Singaporean heartland does not have a lengthy history. The first HDB estate—Queenstown—was constructed in the 1960s. The large satellite towns like Ang Mo Kio and Yishun were built in the 1970s and 1980s. Yet, the term ‘heartland’ did not emerge until a decade later.

Prior to the 1990s, everybody used the term just as the Oxford English Dictionary intended. In LKY’s various speeches—found in the National archives—he spoke of the great ‘Euro-Asian heartland’, and warned westerners against the ‘communist heartlands’. But there were no references to HDB estates or public housing.

As late as the year 1990, Dr Ahmad Mattar, then Minister for the environment, was still calling Marina Bay Singapore’s ‘commercial heartland’.

In 1991, however, its meaning suddenly changed.

According to Common Ground, Multiple Claims: ‘Representing and Constructing Singapore’s Heartland’ by Professor Angelia Poon, we have Mr George Yeo to thank for this evolution. In 1991, during a Q&A session at NUS, he used ‘heartlanders’ to describe the ‘roughly 600,000 Chinese-educated residents of public-housing’ with a household income of less than $5000 per month.

He characterised these heartlanders as PAP supporters mainly concerned with ‘bread-and-butter issues’. They don’t care about ‘less tangible matters such as the elected presidency’ and will continue to support the ruling party ‘provided it delivers material prosperity.’

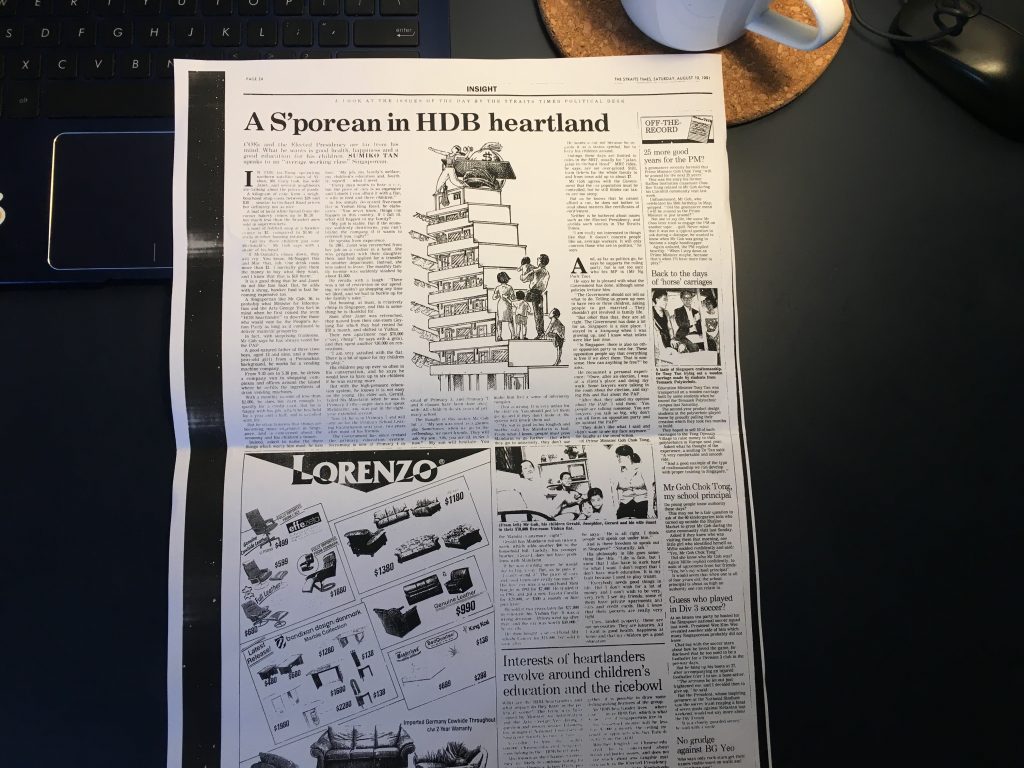

His words were published in the Straits Times on 10 August 1991 under the title ‘Interest of the heartlanders revolve around children’s education and the ricebowl’. The article asked the question: ‘who are the HDB heartlanders and what impact do they have on the political scene’?

To underscore the novelty of this concept, heartland was placed between apostrophe marks. Not heartland, but ‘heartland’.

However, ST answered its own question on the same page with a nearly full-page editorial titled ‘A S’porean in HDB Heartland’. Written by a young reporter on the political desk, it profiles an ‘average working class’ Singaporean named Mr. Gary Goh, who lived in a five-room Yishun flat with his wife and three kids. Exactly as George Yeo describes, Mr Goh is worried about his son’s Mandarin grades, the cost-of-living and the price of car ownership. Unsurprisingly, the first Heartlander ever documented is also a PAP supporter, who believes ‘these opposition people’ will say anything to get elected.

But what’s most surprising was the name of that young reporter responsible for bringing George Yeo’s theory to life with her—um—striking portrait of heartland Singapore. It was none other than our own Carrie Bradshaw, Sumiko Tan.

2 years before she began blogging and 22 years before her appointment as ST’s Executive Editor, Sumiko Tan changed our landscape forever by helping to create the ‘heartlander’.

The Midwife: Goh Chok Tong

For reasons lost to history, the term ‘heartland’ went (the 1991 equivalent of) viral and entered our vocabulary. Soon, Ministers began using the phrase in earnest and so did SPH journalists. They shed the ‘air quotes’ of 1991, and began writing about the heartland as if it were a place that really existed outside of George Yeo’s political imagination.

Minister Wong Kan Seng, at the opening of Junction 8, referred to the Bishan as a ‘HDB heartland’, and so did ST veteran Chua Mui Hoong, who seemed especially fond of the phrase. It was apparently so popular that one 1992 ST article began with the following sentence: ‘Remember the term HDB heartland, much in vogue last year to describe residents in public housing estates?’

However, the story doesn’t end here. While Sumiko Tan and George Yeo were responsible for coining the term, it was then Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong who truly ushered the word ‘heartland’ into public consciousness.

In 1999’s National Day Rally Speech (’First-world economy, world-class home’), he divided Singapore between ‘heartlanders’ and ‘cosmopolitans’.

The former were Singaporeans whose interests were local rather than international. They were ‘taxi-drivers, stallholders, provision-shop owners, production workers and contractors’. Their skills were not ‘marketable beyond Singapore’ and should they emigrate, they would probably get stuck in the Chinatowns of Sydney or Los Angeles.

There, PM Goh claims, they would probably open a Chinese restaurant and call it an ‘Eating House’.

Phua Chu Kang is a typical heartlander, GCT notes, Tan Ah Teck is another.

In contrast to this rather pathetic figure is the ‘cosmopolitan’, who can ‘speak English but is bilingual’. The cosmopolitan is a PMET with a good income. They are upwardly-mobile, comfortable with global capital and thus indispensable to Singapore’s economy.

They are the ones who shall ‘venture forth in the hope of spectacular success’.

Heartlanders, argues Mr Goh, ‘play a major role in maintaining our core values and our social stability’, but they must also understand the role fulfilled by ‘cosmopolitans’, who ‘generate wealth’ for our nation and turn Singapore into ‘an efficient, high-performance society’.

If the condescension of GCT’s voice is rather off-putting, take a deep breath and remember it was 1999. Marina Bay Sands was still a grass patch and most of us were getting disconnected from the internet by other people picking up the phone.

Nevertheless, this speech was—in Prof. Angelia’s words—a ‘controversial milestone’ in the heartland’s history. Whereas George Yeo was careful (or tactful enough) to sketch the heartlander in purely socioeconomic terms like income or address, Goh Chok Tong had no such compunctions. In his worldview, Singapore’s future clearly did not lie in the heartland or with deficient heartlanders. Lip service to ‘core values’ aside, the heartland was clearly relegated to the periphery, subservient to a ‘cosmopolitan’ elite.

Post-Natal Care

Here’s the real question: if the term was so controversial, why bother creating it at all? Why bother separating the wheat from the chaff? Why repeat the heartland rhetoric ad nauseum?

One possible interpretation is ‘political sleight-of-hand’. According to Professor Angelia Poon, the speech ‘disclosed an implicit recognition by the state that globalisation and its associated neo-liberal cosmopolitanism would strain the nation’. The heartland/cosmo divide was thus a blatant attempt at pre-emptive turd-polishing—to ‘finesse a political virtue’ from the irredeemable shit of growing income inequality.

In plain English: Knowing that middle-income HDB dwellers might feel fucked over by their plans to make Singapore into a global city, our politicians attempted to salve the butthurt by conferring symbolic ‘honorary’ ‘title’ of heartlander.

I laughed when I read this, but it is—even by my standards—a rather cynical interpretation of the Singapore heartland. A slightly more optimistic understanding can be found in ‘Contours of Culture: Space and social difference in Singapore’ by NUS Professor Robbie B.H. Goh.

In his view, the heartland was not created as a means of rebranding economic apartheid, but as a means of protecting the HDB community from ‘potentially destabilizing values’ and the ‘influences of globalisation’. Just as Marina Bay Sands sought to ‘contain’ the vice of gambling, the HDB heartland was created to preserve a value system based around ‘inward-looking safety’, ‘family values’, and ‘local orientations’.

It serves, in essence, an ideological condom. That’s why we turn a blind eye to Orchard Towers but howl with outrage when sanctioned vices like prostitution or gambling are found in Toa Payoh. There is one set of moralities for the heartland and another for the more liberal, outward-looking “city centre”.

Either this, or you can simply think of the heartland as a nation-building trope.

To quote Dr Terence Chong in Manufacturing Authenticity: The Cultural Production of National Identities in Singapore, all nations depend on ‘regimes of authenticity’. Nation-states always attempt to ‘inscribe the nation-state with timeless values’, because these eternal values help anchor the nation against the erosive effects of ‘modernity’ and ‘capitalism’.

In Singapore, this authentic figure is the ‘heartlander’, or more specifically, Jack Neo’s version of a Heartlander. He is a Chinese male who ‘typically resides in a HDB flat in one of the many satellite towns, holds a blue-collar or low-paying white-collar job and is most linguistically comfortable in Singlish’.

Although he clashes against cosmopolitan forces like the ‘English-proficient elite’ and is victimised by ‘global capitalism’, mostly in the form of job competition or rising costs, he always triumphs in the end. In Jack Neo movies, there is always a happy ending, however contrived. Because without it, the heartlander cannot become a ‘stable site of down-to-earth values upon which the Singapore nation should be ideally premised’.

There is, of course, an obvious racial bias. The uncomfortable truth is, in most iterations—Sumiko, George Yeo, Goh Chok Tong, Jack Neo—the heartlander is forever and always a Chinese person. Usually, a heterosexual Chinese male breadwinner in his mid-thirties. Despite the HDB ethnic quotas distributing the different races as uniformly as lettuce on my footlong, the heartland’s creators neglected to consider the existence of minority heartlanders, who are unlikely to open ‘Eating Houses’ in London’s Chinatown.

Although it has mostly shed this racial dimension, nevertheless, it was a term originally reserved for ‘working-class, ethnically Chinese Singaporeans’.

28 Years Later

These days, the term heartland is used like Panadol—much too frequently and without any consideration. Journalists no longer speak of Bedok or Yishun unless there’s a murder, otherwise, it’s just ‘the heartland’. Likewise, many identify as heartlanders, without giving much thought to what the term actually means.

If I own a 5-room top-level HDB in Marine Parade and an Audi, am I still a heartlander? What if I profess an interest in LGBTQ issues? If I grew up in a HDB but have since moved out or ‘upgraded’?

There are no correct answers to any of these questions, but it’s worth asking because they demonstrate how slippery the language really is. What started as an electoral demographic in George Yeo’s GE 1991 strategy has slowly expanded into an amorphous, blanket term—a shorthand for the real, authentic, born-and-bred Singaporean.

I don’t know if the invention of the heartland is good or bad. However, its curious origins are certainly interesting to consider because it allows us to rethink so much of our received wisdom.

The ‘average’ heartlander is often assumed to be politically indifferent, concerned solely with bread-and-butter issues, socially conservative, materialistic and inward-looking. He or she cares more about the price of kopi than the costs of POFMA. Without the patronage or guidance of forward-thinking elites, they are doomed in the global economy.

How much of this is true and how much of it is Sumiko Tan’s imaginaton? That is the real question. What if the real heartland is a great deal more diverse than we often imagine it to be?

I’d like to think so. But then again, I’m not a real heartlander. I’m just another twat living in Yishun.

Am I a heartlander? Let me know at community@ricemedia.co.