Raffles Place at 6:30 AM on a weekday morning is unlike anything you’ve ever seen or experienced.

Dark and devoid of its usual madding crowd, the area is calm and eerily quiet. So quiet I can almost hear the tall buildings heave a collective sigh of resignation, steeling themselves for the onslaught of office workers who will soon swarm the area.

For now though, time is kind. The pursuit of money and KPIs has been paused—the calm before the proverbial storm.

But not for long. Suddenly, the silence is broken by the sound of metal dragging along concrete. Ah, yes. The man I’ve been waiting for is finally here.

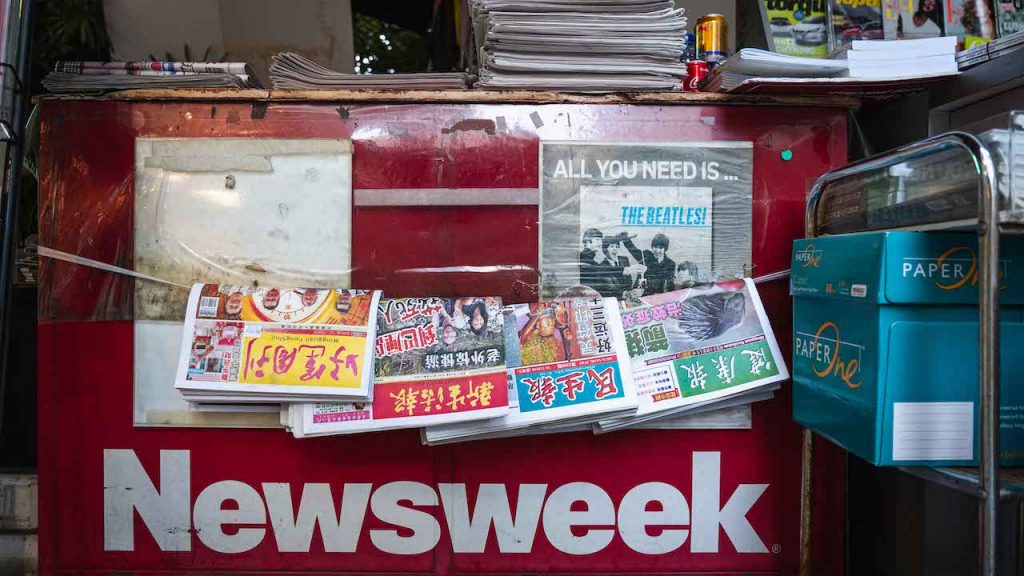

Turning in the direction of the noise, I watch him slowly set up a large, rickety table before hauling his wares onto it and carefully arranging them. Once done, he crumples into a small plastic chair under a giant umbrella that will shield him from the elements, visibly tired from his efforts.

To the hordes of people who pass him by daily, he’s become part of the landscape—someone they might recognise but don’t know. However, it’s this man who perhaps knows this place the best.

From the buildings which have been torn down and rebuilt, to the shop-front windows that change with the seasons; from the seasoned big-wigs with their Patek Philippes, to the baby-faced fresh graduates eager to prove themselves in the corporate world, he’s seen wave after wave come and go from the relative comfort of his humble newspaper stand.

After saying hello, the man’s expression changes slowly from one of shock (I assume not many strike up a conversation with him) to plain amusement.

“Why do you want to talk to me? I’m not a big, influential figure. I’m just an unknown; a nobody,” he says dismissively in Mandarin.

But before I get a chance to protest, he continues:

“What I’m doing isn’t important. It doesn’t affect anyone. I just sit here selling newspapers and only the people that buy them might know me. But after they take a copy, they just forget. People will say it shouldn’t be like this and you can tell me I matter. But this is how it is—very realistic. You’re a journalist, you should know.”

And he’s right. But only about one thing. I am a journalist, which means I know everyone has a story to tell.

In this day and age of ever-evolving technology—where people get their news instantly via their phones or laptops—this man’s newsstand has managed to survive, sticking out like a sore thumb amidst the orgy of polished glass and concrete.

So I want to know everything: from how he’s done it, to how long he’ll remain the unofficial keeper of the CBD.

After a solid 15 minutes of persuasion, the man relents.

He tells me that he gets out of bed slightly before 5 every morning to have breakfast and to pack lunch for his wife (who helps him at the newsstand) and himself because “here, things are very expensive.”

At 6, he makes the drive from their home in Jurong to the CBD to collect his newspapers from the district’s wholesaler, before quietly setting up his stall and waiting for his regulars and other potential customers.

He says that the alternative would be to go straight to SPH to get his papers since prices are “still okay”. But after crunching the numbers (parking, ERP and petrol costs, and multiple trips since different newspapers are published at different times of the day), it just wouldn’t be worth it. He’s already not making a lot—much less as compared to the old days—and simply can’t afford it.

But this doesn’t mean Mr Chan is a penny-pinching miser. During the course of our interaction, I hear him say “just take, just take, don’t need to pay” in Cantonese to a few of his regular customers.

12 hours later, his workday finally ends. He stows away his table and lugs the unsold newspapers and magazines to his van. But he doesn’t go home. Instead, Mr Chan heads for the offices that tower over him daily.

“Other than this [job], my wife works as a cleaner/pantry aunty. When the office workers leave for the day, she will go up to clean the place. She isn’t in the best health so I go up to help her.”

All things considered, Mr Chan ends work at around 9 and gets home close to 10 PM. His stern countenance lightening, he laughs as he tells me that more often than not, he falls asleep while watching the nightly news.

“I don’t know if I watch TV or the TV watches me!” he chuckles.

Before he knows it, another day begins and the cycle repeats. Day in and day out, come rain (he has a plastic tarp to cover his wares) or shine.

Rolling back the years, Mr Chan shares that he used to work as a ship captain in Jurong Shipyard. Back in 1969, when he was just 24, Mr Chan entered the industry in the hope of learning electrical engineering—something he found interesting and felt was a useful skill to have. However, he didn’t meet the necessary requirements and wasn’t of the appropriate rank to do the job he wanted.

As a result, he was posted somewhere else with a completely different job scope. Instead of getting upset, Mr Chan took it in his stride, and shares that life was still good.

“The relationships I had with my colleagues was very good. Whenever we got bonuses, everyone would just treat everyone and it was like we were one big family. That’s why I stayed there for so long.”

30 years long in fact. But everything changed when the Asian Financial Crisis hit. Also, in the case of Mr Chan, when it rains, it pours: it was around then his mother passed away as well.

Suddenly out of a job on the wrong side of his fifties, Mr Chan shares that he found temporary work as a cement truck driver before leaving to work in his friend’s restaurant. Over the next 2 and a half years, he stood for hours on end making the restaurant’s sauces. But his age, coupled with all that time spent on his feet, meant Mr Chan was constantly in pain.

Knowing he wouldn’t last, he started looking for alternative means of employment and applied for different sorts of licenses—one of which would allow him to operate his current newsstand.

At this point in Mr Chan’s story, I learn two things. First, he’s not one to get too comfortable with life, and constantly thinks of how to upgrade himself and his skill set. Second, his humble newsstand has been in existence longer than he’s been in the business.

But this is not a case of taking over the family business. Rather, it was just Mr Chan adapting to his circumstances.

Unfortunately, getting the license in the first place was far from easy. The permit his late mother had was non-transferrable—despite him being the next-of-kin—and Mr Chan had to apply all over again. He was rejected thrice. On his fourth attempt, the relevant authorities finally gave in.

“I didn’t want to sell newspapers but it’s better to have another license than to not have any. But the thing is that if you don’t use the license, you don’t get to keep it.”

Left with the choice between selling newspapers or driving a taxi (he obtained his taxi license soon after deciding to leave his job at the restaurant), Mr Chan picked the former, owing to his unfamiliarity with Singapore’s roads.

“It’s not that I want to praise myself or show off but back when I was working in the shipyard, I worked every day—weekends, holidays, the lot. And so I only knew two places: my home and Jurong Shipyard. I didn’t go anywhere else and was bad at directions,” he tells me in his unassuming, humble nature—which I soon realise is his trademark.

He used to be able to sell over 200 copies of the Straits Times each day to aunties who worked as cleaners and hawkers nearby, as well as the office crowd that was perpetually in a rush. Office ladies would come down during their breaks to chat and flip through magazines; Her World, Female, and Women’s Weekly were his bestsellers.

But the small smile on Mr Chan’s face fades as he snaps back to reality.

“That was back then,” he says dejectedly, before newspaper prices went up; before the older generation left, either retrenched or retired; and long before the advent of the internet and smartphones.

7 years ago, as everyone started getting their news via smartphones and tablets, Mr Chan’s business took a nosedive. And it hit him hard. From just being able to make ends meet selling 200 copies of newspapers a day, sales dropped to only 30, putting an even greater financial strain on him.

“I have to buy in bulk for costs to go down but I can’t do that anymore since not a lot of people buy physical copies [of newspapers]. Now there’s no business, and I’m old and weak, I feel very disheartened. I have no motivation to carry on.”

Looking around at his newsstand, Mr Chan slips turns pensive, momentarily lost in his own thoughts. I wait patiently for him to speak again, and eventually, he tells me that this might be his last year in the business.

Hearing that the unofficial ‘icon’ of Raffles Place might be leaving both shocks and disturbs me. Perhaps it’s because I regret not befriending him sooner before his fades into obscurity, or maybe it’s because I’ve always found comfort in the scene of a “common man” trying to make a humble living in a world full of powerful suits and ties.

Whatever the case, a part of me desperately needs to know if this place means anything at all to him. I ask if he has any fond memories of the area he’s spent a good chunk of his life in. After all, from our conversation thus far, Mr Chan sounds more like a man hardened by life who’s resigned to his fate rather than one who’s sentimental.

But his answer surprises me. Gesticulating at the people walking past us, Mr Chan once again breaks into the faintest of smiles and shares that though he might not mean much—if anything—to them, it’s actually these people who brighten his day.

“Some of them see us two elderly folks and occasionally buy mi fen or tea for us. It’s not that I’m greedy but it’s just … a nice gesture you know? And then there are those who tell me they “support” us and only buy newspapers from us, even though somewhere else might have their papers delivered before we collect ours. It’s things like this that make me feel very touched.”

It’s not always rainbows and butterflies though. Mr Chan has encountered those he says obviously look down on him, throwing/slamming coins down on his table before walking away nonchalantly with their morning paper. Then there are the looks he gets on the train after a hard day’s work.

According to Mr Chan, people do give their seats up for him, but because he’s dressed poorly or has worked up a sweat, there are always judgemental sideways glances he has to deal with. “You can tell they’re not 100% happy,” he says, puzzled as to why some look down on him despite not knowing who he is.

Nevertheless, he chooses to focus on the good in people.

“At the end of the day, I still believe that there are more good people than bad in this world. Otherwise, we’re doomed!” he says, a look of mock exasperation on his face.

Slipping back into melancholy, he continues:

“I’ve seen a lot of changes happen to the people here and the place itself. Now all my older customers are on wheelchairs or walking with canes. I almost cannot recognise them anymore, and the younger ones don’t know me.

“People come and go, but I’m still here.”

Perhaps I alone can’t accomplish great things.

But with my best, I devote all of my little strength.

Perhaps I alone can’t shine like the brightest star.

But for my little world, I shine bright enough.

I’ve never been bothered that I’m not a big shot.

Because being ordinary is a kind of happiness too.

I see celebrities being busy all the time.

Yet, my time is in my control.

An ordinary life is fulfilling all the same.

It’s the lines about seeing busy people passing by and having control over his own time that he quotes most often.

Only after looking up the song up at home and carefully examining its lyrics do I suddenly get it.

Under a weather-worn red umbrella in a corner of Raffles Place, Mr Chan knows that his business has been living on borrowed time, and that it’s fast catching up to him.

In fact, when I ask him what he’d change if he could turn back the clock, Mr Chan tells me that he’d love it if the world didn’t progress at the speed it did. As part of the older generation of Chinese-educated Singaporeans, he feels that rapid westernisation has left him perpetually playing catch-up. He feels he’s been left behind.

With each passing day, this sentiment gets drilled home even harder. Amplified by the fact he’s surrounded by the same sort of people who past his newsstand daily, Mr Chan has learnt to accept his place in the system—as evidenced by the lines in the song he constantly refers to. To him, it’s acceptance. To me, it’s sad resignation. It doesn’t matter though. It’s just how he copes.

Constantly feeling that intangible distance between others and himself, Mr Chan is wary of strangers and judges a person on the most basic of metrics: their sincerity and manners, especially how they treat those beneath their social stature.

As mentioned earlier, I was squatting by his side for the longest time but as I listened intently to his story, he gradually trusted me enough to invite me to have a seat. Later, he even offered to make me a cup of coffee. Before I left, I picked up a copy of the Straits Times for my mom, asking him to keep the change. He refuses.

“Us businesspeople have to have morals and values. I cannot anyhow take. Even if the ultimate goal is to earn money, [you] cannot just take if it’s not yours,” he says, despite my insistence.

In many ways, Mr Chan is the embodiment of what working life in Raffles Place is: nose constantly to the grindstone, soldiering on come rain or shine, and just making it work. But he also represents the side of Raffles Place that isn’t often seen: the human element. That what truly matters is who you are and what you’re like, minus your fancy office wear and university degree.

Under a weather-worn red umbrella in a corner of Raffles Place, I manage to find the only place in the CBD where the two exist in perfect harmony—where time stands still, untouched and divorced from the flurry of activity in the area.

I just wish time—for both Mr Chan and me—stood still a moment longer.

Have you also seen one gaze frozen in time? Tell us about it: community@ricemedia.co