This is the first in a two-part series examining single-fatherhood as a deliberate choice in Singapore.

A child, more than all other gifts

That earth can offer to declining man,

Brings hope with it, and forward-looking thoughts.

—Wordsworth, Michael: A Pastoral Poem

This is what I confessed to my mother, in a pensive mood, a few years after my father died. True to typical Singaporean fashion, she was thoroughly aghast at the suggestion.

My love would simply not be on par with what a couple could give a child, she said; I wouldn’t be enough. Beyond that, a single-parent family was morally blasphemous and heinously “broken”.

To say that I was indignant is a given. To say that I was heartbroken is an understatement. It might be hard for some to conceive of why a man would want to be a single parent, but here I am, as living proof.

For those who undertake it, parenthood makes draconic demands of immense proportions. There’s no going back from having a child, and you can’t just cast them back into the void of non-existence and say, “That’s it, I quit.” Saying yes to a child is a promise to nurture and bear responsibility for another life, for life.

To understand my desire, we need to start with my relationship with my parents.

For them, my birth was somewhat of a second-coming; they had tried for five years to give my sister a sibling before finally succeeding.

Depending on the context it gets retold in, this story expands, shrinks, and gets tinkered around with. In the boisterous company of family and friends, I’m the happy ending of a passion-filled night on a cruise ship. In the lackadaisical lounging of idle afternoon chats about our family history, I become the blue-skinned newborn who spent much of his early life in and out of the hospital.

For better or worse, I grew up having my optimism tempered with a healthy dose of cynicism. There are many things I no longer believe in, but the desire to be a father remains and continues to be an anchor—my own little north star if you will.

Yet, it never occurred to me that I had to find a partner or get married; I wanted to be a father—not a husband or a boyfriend.

These days, the Grand Narrative™ for everyone continues to be: study hard, get a job, find a partner, settle down, and start a family. We assume romantic love to be the precursor to everything familial, and so much depends upon the boy-meets-girl scenario.

But what if said boy never meets the girl of his dreams?

What if love like that is not for me?

Not everyone has someone out there, waiting for them.

I was 16 when my father died of cancer.

In the first weeks after he died, my mother couldn’t bear to sleep alone. It’s been years since then, but on the nights I get home late, I still see her sleeping with the lights on, her lonesome figure outlining the negative space of his absence.

This reminder of the inherent bleakness of pursuing, having, and losing romantic love has left me with a bitter ambivalence. Romantic love may be nice to have but I don’t want it to become the overriding directive of my life. My life should have fulfilment and meaning regardless.

One of the greatest potential sources of fulfilment I saw for my life was parenthood. The allure of family life, even though it seemed far away, kicked in; it kicked in even harder after my father died.

I’m a cynical realist when it comes to love. There are seven billion people on this earth, and no matter how you crunch the numbers, someone’s going to end up alone in a flat with seven cats.

And I’m not alone in feeling this way. The 2016 Marriage and Parenthood (M&P) Survey found that 27% of single millennials (aged 21-35) did not intend to marry, and 59% of single respondents were not dating with a view towards marriage.

So why shouldn’t a single man plan to be a father all by himself?

We do not accept unmarried single-parent families.

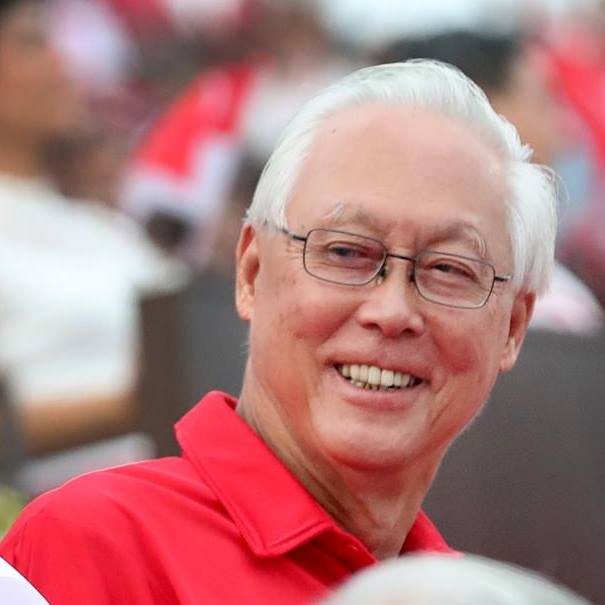

Then-PM Goh Chok Tong arguably got the ball rolling in 1994 with his National Day Rally Address, when he revoked the rights of unmarried mothers to buy flats from HDB, alleging that the removal of stigma would encourage the wide-spread proliferation of single mothers in Singapore. It was made clear that in the eyes of the government, alternative family structures were considered “broken”. At one point in his speech, it was declared that “we do not accept unmarried single-parent families”.

The de facto Singaporean family structure has always been the sacred trinity of Mother, Father, and Child. Nothing else is permitted to exist visibly and without shame.

In 2017, a petition led by single parents calling for authorities to recognise unmarried parents and their children as a family nucleus in the context of public housing policy was rejected. In December that same year, the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) made clear that “planned and deliberate parenthood by singles” is antithetical to the enshrined dogma of ‘parenthood within marriage’.

Singaporean public policy is deathly afraid of any alternative; these were just two moments in the history of official government efforts to entrench the idea that parenthood is only permissible in the context of marriage—a heterosexual one at that, if it wasn’t clear enough.

In 2016, changes to the Child Development Co-Savings Act (CDCA), extended maternal leave and Child Development Account benefits to unwed mothers, granting them the same rights as married mothers.

In March 2018, housing policy for single parents was relaxed; divorcees can now buy or own subsidised a subsidised flat immediately upon ending their marriage, without a debarment period of three years as per previous policy rules.

While the slew of housing schemes that have been made available to single parents suggest that the government has accepted single-parent families in Singapore, it’s worth noting that they only apply to parents made single by death or divorce.

There persists a constant, reinforcement of parenthood within marriage—heterosexual by default—and hidden assumptions towards single-parenthood at the policy level spill over into the social sphere.

A set of heterosexual parents is still deemed mandatory for a child to develop healthily. It continues to be assumed that mothers are needed to provide emotional support and domestic care; to handle the ‘softer’ facets of family life, while fathers are needed to teach emotional resilience and discipline; to take up the ‘tougher’ facets of family life. In line with this, a single parent can’t provide for all the needs of a child.

A legitimate family is only complete and whole with a set of heterosexual parents. It’s not uncommon to hear of fathers citing an inability to interact with their chilren with a “gentleness” that’s on par with a mother.

It’s hard to say that the government whole-heartedly supports single-parenthood when family and reproductive policies continue to discourage the intentional creation of single-parent families. Adoption and surrogacy continue to be highly inaccessible options for most Singaporeans. More infamously, if you’re single, you’re doomed to have to wait till you’re 35 or older to receive state-sponsored aid for buying a flat.

But since my father had passed away, were we not a single-parent family?

Did she consider us a “broken” moral blasphemy as well?

This observation left her in exasperated silence, and since then, we haven’t had this same conversation. In hindsight, I regret my pointed remark. I should have had the patience to clarify my intentions.

To be fair, I don’t blame her for what she said. It’s not that she’s not open-minded. Her attitudes and values are merely the results of years of state narratives and policies, shaping what she thinks a ‘proper’ family should look like. If anything, I see her remarks as a declaration of her unyielding love for me: who would desire anything but what they think best for their child? And in a way, I now see this as a challenge to prove her and other naysayers wrong.

If we were to apportion blame, perhaps the state should take significant responsibility for its pragmatic cookie-cutter approach to family planning. But at this point, blaming hardly seems like the right course of action.

What we should do instead is look forward.

In rethinking how we define a family and how we can enable planned single-parenthood to be a valid and viable choice in Singapore, we may yet create a more inclusive society.

As far as public policy in Singapore is concerned, the inevitable silver tsunami of an ageing population has been bemoaned since time immemorial, yet our fertility rates haven’t seen a commensurate increase. Insisting upon parenthood within marriage could be exacerbating the problem.

So rather than restricting parenthood to the confines of marriage, why don’t we start encouraging single-parenthood and empowering singles to aspire to family life beyond the rigid confines of marriage?

I know that to be young is to be uncertain.

But for me at least, I know that in the quiet moments when I’m thinking about the life ahead of me, I am also always thinking of the children that I want to have—partner or no partner.

So to my mother, my father, and anyone else who’s concerned:

I want to be a single father.