This is the first in a two-part series.

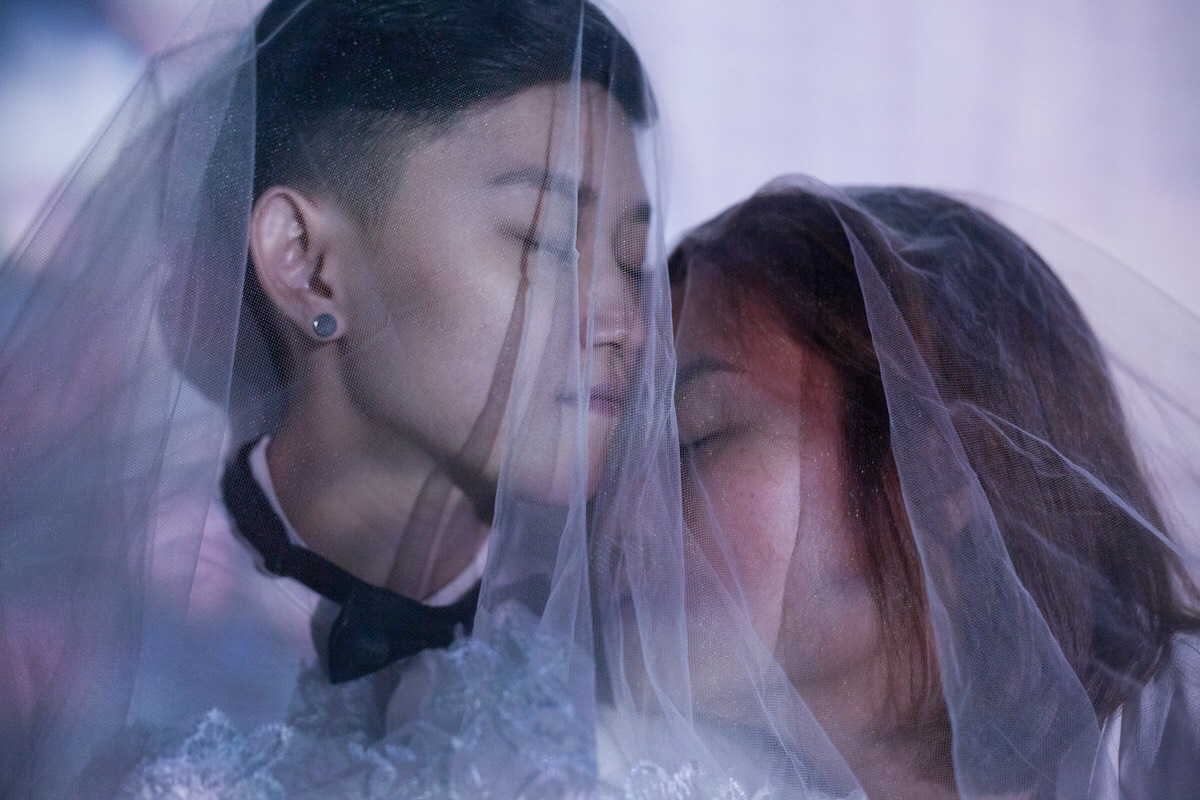

Nic and Jackie (not their real names), a cisgender lesbian couple, and I are sitting on the steps outside Raffles City McDonalds while they have a post-dinner smoke. If they ever get married or domestic partnered or commitment ceremonied, Nic says, she’d like to use the vows from Robb and Talisa’s wedding in Game of Thrones.

At my raised eyebrow, she says, “What?”

“I’m not judging!” I squawk. (All right, I am, but only at the irony of associating GoT with romance.)

Nic is one of my closest friends. We’ve known each other for years, since we were in school together. In this time, amidst all the other vagaries of young adulthood, I’ve watched her struggle with her sexuality, accept it, come out to her family, reconcile it with her faith, and eventually meet Jackie, the woman she wants to spend the rest of her life with.

All this weighs on my mind as I watch the pair trade barbs, just a few days before the 11th Pink Dot.

When I was first assigned to write a story for Pink Dot and Pride Month, I wanted to move beyond coming-out narratives. Important as these are, I wanted to ask: what about the rest of it; the nuts and bolts that form the architecture of daily life? Pink Dot, after all, is but one day a year, and coming out is but one aspect of LGBTQ life.

It’s what I’m here to speak with Nic and Jackie about, and they have plenty to tell me.

It bears saying, however, that 377A is the tip of the proverbial iceberg. If it were taken off the books today, it would be a massive step forward for LGBTQ rights—but one that, without further policy change, would make little practical difference to the lives of LGBTQ individuals.

One of the clearest examples of this is access to public housing.

“It was quite an informal thing,” says Nic. “She just started staying over every now and then, and it kind of developed from there.”

They’ve been together for nearly two years, and are certain that they’re in this for the long haul. If they were a straight couple, they would probably have applied for a BTO by now, given the average three-to-four year wait for a flat.

Except, of course, they aren’t straight. So they can’t.

Marriage and home ownership in Singapore are inextricably linked, with the latter being contingent on the former. As Dr. Teo Youyenn (of This Is What Inequality Looks Like fame) writes in Neoliberal Morality in Singapore: How family policies make state and society:

“Public housing rules require family formation as a prerequisite for purchase—this is the larger structural reality that all Singaporeans live within. The process put in place by [HDB] rules has become very well understood, and marriage is indeed the dominant route to flat ownership … Because the housing-marriage process seems so ubiquitous, it comes across as something that all but an exceptional few, normatively speaking, should go through in life.”

Those exceptional few—anyone who doesn’t fit the two-person, straight, cisgender definition of a ‘family’—are left to figure it out on their own.

In this, LGBTQ couples are doubly penalised. Being legally prohibited from marrying also puts HDB ownership, at least till age 35, out of their reach, and excludes them from both rites of passage in one go.

One way around this, of course, would be for LGBTQ couples to rent a place together, but not every couple has the means to. Meanwhile, the absence of equality legislation—which, for example, would make it illegal for landlords to discriminate against tenants on the basis of race, religion, or sexual orientation—means that couples who do rent must either put in extra legwork, feeling out prospective landlords or flatmates for homophobia, or keep the true nature of their relationship under wraps.

On Nic and Jackie’s part, renting remains too expensive for now, so they anticipate staying with Nic’s parents for some time. In this, they’re careful to stress, over and over again, that they’re lucky to have this option in the first place—that Nic’s family is as open and welcoming as they are. Not many parents of LGBTQ individuals, they insist, would go out of their way to embrace their child’s partner, over and above accepting their presence.

Nonetheless, uncertainty continues to cast a long shadow over their future.

“Your [Nic’s] mum is very positive, she’s always like, things will work out,” says Jackie. “It’s your dad who’s the realist. He’s always asking, what’s your plan in the long term? How are you going to make this work financially?”

“We always casually talk about the future, like oh, in 3 years’ time we’ll go to Australia and get married and get our papers … sign them in Melbourne or something and have a get-together there, then have a reception in Singapore,” says Jackie.

With same-sex marriage being expressly prohibited here, getting married abroad is an increasingly popular option for LGBTQ couples who wish to formalise their relationship (and have the means to do so).

The party, however, ends at Singapore’s borders. When such couples return, it is to both a state and swathes of society at large that will not recognise their union.

This goes beyond philosophical questions about who marriage is really for or whether it’s enough if the couple is happy. The lack of public acknowledgment manifests in very practical ways.

“Very few hotels will be willing to take bookings from same-sex couples for the [wedding] reception,” Jackie explains, highlighting something I, as a straight, cisgender woman, have honestly never once considered.

“You can try and approach them, but chances are that if you ask they’ll be like, oh no, sorry, we can’t.”

Their fears have precedent. Last year, one cisgender lesbian couple, Gillyn and Jolyn, went public with their account of their relationship, including holding a wedding reception in Singapore after getting married in the US.

As happily as it ended, Gillyn and Jolyn’s story illuminates a whole host of hidden difficulties faced by the LGBTQ community.

Say Nic and Jackie went ahead with their plan to get married in Australia, and wanted to hold a reception here. Even if they managed to find a hotel or restaurant, I wonder, what about all the other elements of the wedding? Where else might discrimination rear its head?

And what about afterwards? Weddings, after all, are but one part of marriage (perhaps one of the least important). Without their union being recognised here, they would still be ineligible for everything from tax deductions to CPF top-ups.

Meanwhile, transgender individuals face a different set of issues.

A couple of days after meeting Jackie and Nic, I meet with Carrie (not her real name), a 26-year-old transwoman in a steady relationship with a trans man. Although they haven’t discussed it explicitly, marriage technically remains possible for them, but requires a careful dance of strategy and timing.

Carrie explains that neither of them have changed their genders on their ICs. As one party is legally a man and the other, a woman, marriage therefore remains possible—but would cease to be if one changed their gender but not the other.

Following a legal case from two years ago, if one of them were to change genders after getting married, the marriage would be voided. The only solution would be for both of them to change their genders first, keeping the one man-one woman permutation, and then get married.

This sounds more like a matter of careful planning than an insurmountable obstacle, and perhaps it is. But then I try to imagine dealing with this on top of wedding planning; of the fear of one administrative error ruining everything, of having to explain myself before strangers’ demanding eyes.

I try to imagine working within a system I feel I cannot trust to defend my well-being, because it has never made me feel valued just as I am.

His first job, in what he describes as a ‘large, government-linked enterprise with a typically conservative environment’ meant there was no question of coming out to his colleagues.

“When I moved back to Singapore and joined the workforce, I felt like some of the more controversial aspects of my personality had to be shaved off, my sexuality being one of them,” he tells me.

“Without anyone saying anything to me about it, or telling me explicitly, I just knew I had to keep it back.”

To this end, ‘coming out’, despite being the accepted term, can be misleading. All my interviewees clarify that it is not a clear-cut binary, where an individual is either definitively in the closet or out of it. Rather, it’s more like Schrödinger’s cat, with an individual being variously ‘in’ and ‘out’ throughout their lives, to different people at different levels.

As such, LGBTQ individuals are never truly done coming out. Even if they aren’t solely defined by being LGBTQ, it remains an inextricable part of who they are. It cannot be escaped; it matters to things both significant and banal.

Jackie tosses me another hypothetical.

“Say we got legally married in Australia and we come back and I have a kid. What would happen if she [Nic] went to her employer and says, ‘I need maternity leave’?”

“What would they say? Is it your kid? No, it’s my wife’s. Huh? So what do you want? There’s paternity leave for dads, but you’re two mums … so how would that work?”

Nic smirks. In her opinion, talking about kids is getting ahead of themselves, what with the legal and financial challenges it would entail. Rather, she asks, what if something happened to one of her parents, and Jackie can’t be there because she’s not legally recognised as family?

“Also, she can’t take compassionate leave because she’s not my legal spouse,” she points out.

Some employers, particularly large, multi-national companies or younger ones with more progressive policies, might permit this. But for LGBTQ individuals who aren’t in such a position, I wonder: how would they broach such a topic with their bosses? Would they even feel able to try?

“Is it worth the pain and trouble just to be able to enjoy a benefit that comes so easily to the rest of the world?” Jackie asks.

“No-one really knows what the day-to-day life of a gay person is like, [b]ecause the small things that come so easily to straight people require so much thinking for us.”

“You know our rules in Singapore. Whatever your sexual orientation, you are welcome to come and work in Singapore,” he said. “But this has not inhibited people from living, and has not stopped Pink Dot from having a gathering every year.”

When I began my research for this piece, I was wary, as a straight, cisgender woman, of wandering into something I had little grasp of, and will never truly understand. I feared I might either over-simplify what I found, painting LGBTQ individuals as uniformly grim and disempowered, or romanticise them into a narrative of triumph against the odds.

This last point is for readers to judge. But I read PM Lee’s comments with both incredulity and a heavy heart, because an inhibited life is the lived reality of many LGBTQ people in Singapore.

As Carrie put it, “Some people seem to think that coming out will solve their problems, but it does not. You have a person and the world they function in. [In my case], transitioning changes the shell of the person, how they present themselves, but it doesn’t change the fact that the world is still the world.”

It is less a question of whether the Singapore Dream is attainable for LGBTQ people than whether it is available to them in the first place. To have this option at all, I realise, is an immense privilege; to be able to reject the good-job-HDB flat-marriage-kids narrative, if I so choose, rather than being excluded from it from the start.

None of this is to say that LGBTQ people cannot, or do not, enjoy rich and meaningful lives. That would be both wrong and condescending. But a great many of them, even those in positions of relative luck and privilege, are intimately acquainted with what it means to live by halves; to go through life expecting that what so many take for granted will never be theirs.

Neither Jackie nor Nic believe that 377A will be repealed any time soon. It grates on them that their love might never be given the respect it deserves, but this is something they’re resigned to.

“I just feel like if it’s so hard for people to take that millimetre of a step [by repealing 377A], then I have little to no hope that we’ll ever be legally recognised as a couple, be it marriage or a domestic partnership,” Jackie tells me.

“If it does happen, maybe we’ll be like one of those old couples in Ireland that got married at 80 in wheelchairs, and we’ll be like,”—she pretends to wheeze—“Look guys, we finally did it.”

Have something to say? Tell us what you thought of this story at community@ricemedia.co.