Amidst local news and discussions revolving around burnout, millennial dissatisfaction at work, and battles with mental health, there’s a recurring piece of advice meted out by older Singaporeans:

Suck it up, youngsters. Your experiences are nothing new. We have been through worse.

Recently, Today published a commentary piece about youths’ increasing anxiety over a future of economic uncertainty. The author and I are both undergraduate students rapidly approaching the end of our formal academic journey and praying we don’t fall flat on our faces when we are finally thrust into the Real World.

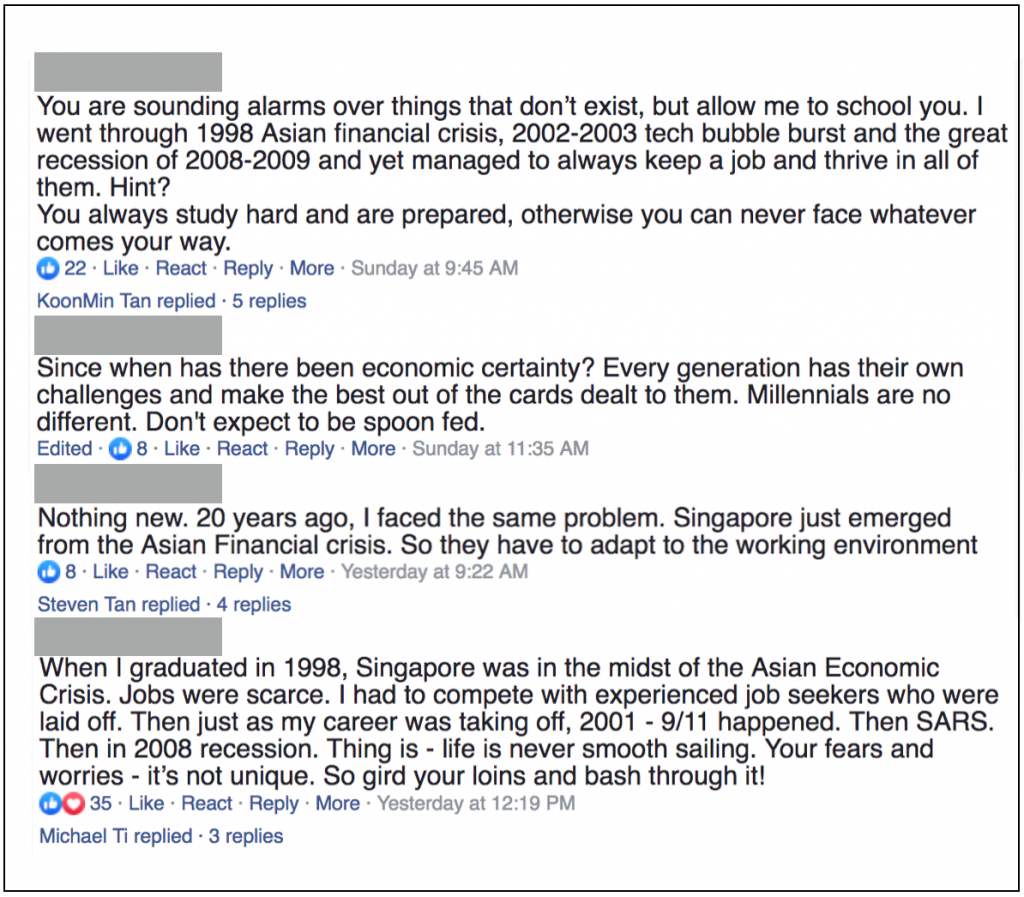

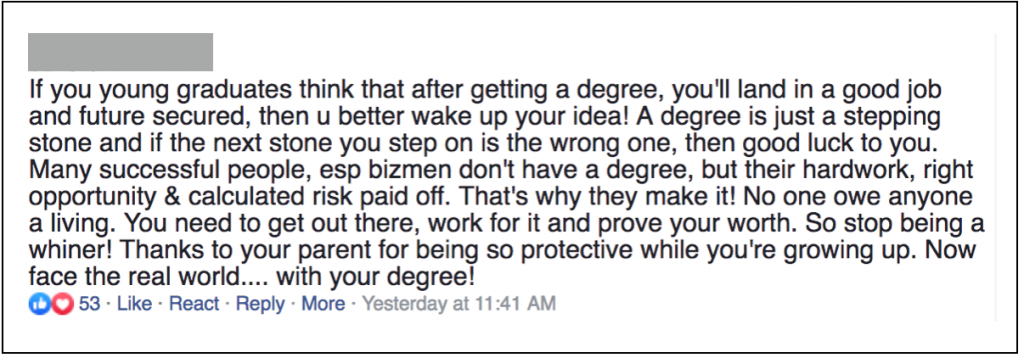

Yet, the Facebook comments, predictably, insinuate that this just proves how easily-bruised we sheltered strawberries are. If scathing Facebook comments are anything to go by, millennials are the generation that whines the loudest—especially on social media—about their inane first world problems… all the while sipping Starbucks cappuccinos from their eco-friendly keep cups.

Of course, it is important to be constantly reminded of my position of privilege. My grandparents and parents have “slogged like pigs” (direct quote from my Grandma) to secure a better future for subsequent generations. It is because of them that I can even consider pursuing a career of passion and fulfilment, rather than just something that pays the bills.

But it frustrates me that many older Singaporeans continue to respond to the anxieties that millennials face today with a resounding lack of sympathy or empathy.

For starters, our fears and worries ARE unique. Wrestling with economic disruption might not be a unique situation in itself, but the anxieties that millennials carry with them are legitimate and distinctive.

As the Today piece explains, unlike generations that have come before (and after) us, millennials have been told that the roadmap to success is simply to “study hard, get good qualifications, get a job”. As long as we put our minds to it, “there’s nothing [we] couldn’t achieve”.

It’s only quite recently that this mantra has descended into jumbled, dissonant disarray.

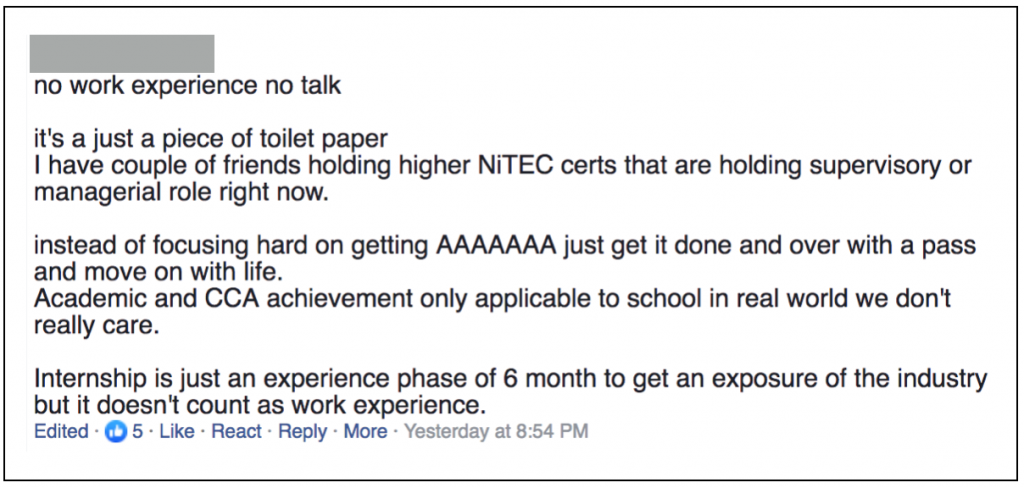

First, the government has changed its tune. Innovation and creativity have become buzz words in recent years, and MOE is veering away from pure academic excellence to focus on holistic education/applied learning/value-adding, whatever you choose to call it.

Pressed to remain competitive amidst a rapidly developing region, the government stresses that education is now more about teaching students how to stand out from the rest. Our myopic obsession with grades simply can’t achieve that.

Then, educational institutions followed suit, injecting seminar-based discussions, compulsory internships, encouraging students to take on extracurriculars on top of their already packed academic schedule.

But these policy changes are only coming when the ship has already sailed. For those of us currently still in university, graduation is creeping ever-closer, and it’s difficult to make a hard turn and go a completely different direction at this point. For those in the workforce, or fresh graduates making their debut, they feel the pressure of a potential recession.

Many of us are desperately trying to cover our bases, padding our portfolios with academic and non-academic achievements. Yet we’re perpetually anxious, because we know that the system of meritocracy is bullshit. Working hard doesn’t guarantee success anymore.

We know that the system is flawed. It prioritises the privileged, who have both the resources and connections. Of course, that’s just the way life is. But knowing that, we still try our best to push through the throng, desperately fighting to come out on top in a system that feels wholly unfair.

We’re left feeling stranded in open sea, paddling with tiny oars and turning full circles.

Another thing: it’s just not helpful to say everyone is suffering so we should just suck it up and stop complaining.

A study conducted by Harvard Psychology found that people who have experienced hardship are less likely to show compassion for others who struggle to cope with a similar ordeal. In fact, they are actually more critical.

One of the suggested reasons for this is what is known as the empathy gap. When people recollect about a tumultuous period of time they’ve previously experienced, they tend to only vaguely recall that it was a difficult and trying process, while underestimating just how painful the experience felt in the moment. That is, they forget just how painful it really was.

Additionally, people who’ve already overcome the adversity know they were able to successfully overcome it, which makes them feel confident enough to assess the situation and criticise how other people are dealing with it.

So maybe this explains the surprising lack of empathy from older Singaporeans, and the weird combination of triumph and derision that some seem to lug around.

To be fair, another reason for their lack of empathy is because many of us millennials do have most of our material needs met, while in the past, these needs might have been the only priority.

I’m thankful for the sacrifices my parents have made for me, be it spending late nights in the office, or having to come home to attend to the children and grandparents even after a long day at work.

But something that my parents have really emphasised over the years is that, in some ways, they really wish that I wouldn’t follow in their footsteps. The opportunity cost of spending long hours away from home and devoting their waking hours to their career was them missing out on precious moments with growing children and ageing parents; it meant not having a real social life for the past decade.

I’m not diminishing the trials and tribulations of their era, but they’ve made it abundantly clear that they don’t want me to be put through the same gruelling circumstances that they have.

Again, this ties it back to the discussion of privilege. But the point that I’m trying to make here is that while people are quick to say things like “I had it much tougher back in my day”, in the moment they sometimes forget that these aren’t the conditions they would wish upon the younger generation.

Progress is about moving forward, not looking behind.

So other than acknowledging that the strawberry generation is experiencing their fair share of legitimate struggles, let’s try and keep society from descending into a culture of unbridled condescension and cynicism.

Let’s allow young people to vocalise their anxieties. Maybe if you dig deeper, you’ll realise you might really resonate with their experiences and affirm them for what they’re going through. Being uplifting and genuinely empathetic is a way more productive way of engaging in any conversation, in my opinion.

Or at the very least, we can all just commiserate in our shared misery.