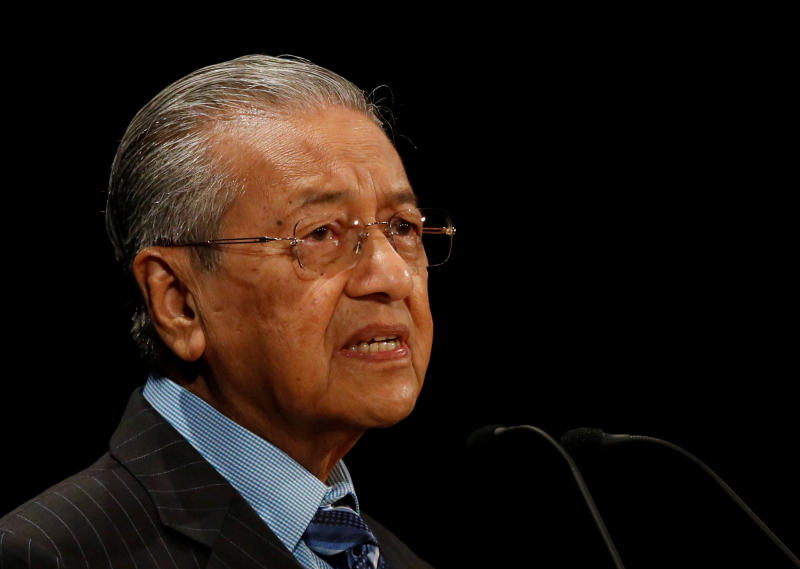

But across the causeway, iron and bruised knuckles haven’t gone out of style. Today marks one year to the day Dr Mahathir Mohamad, aka Dr M, Malaysia’s fourth (and currently seventh) prime minister, was re-elected to the office he once held some 30 years ago.

It’s hard to imagine now, but 2015 Mahathir was little more than a squawking lame duck; an “inveterate meddler”; a living fossil that refused to die.

Never was a man so universally hated in the political sphere: he was dismissed from his party, disdained by the three prime ministers who preceded him, and derided by the two that came after.

Yet, he managed to outlive them all, metaphorically and literally. Internationally, he was known for an iron-fisted rule that fiercely curtailed civil liberties, drawing sharp criticism from foreign governments and rights groups.

Sound familiar?

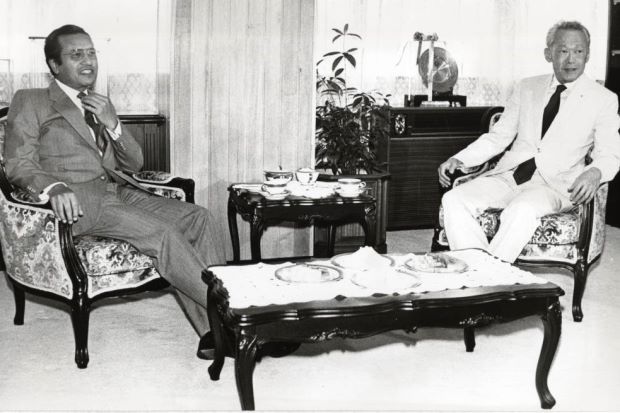

Even before he was elected leader of Malaysia, Dr M spent his political career fiercely attacking Singapore, the PAP, and LKY. As a strong supporter of Malay entitlements, Dr M saw the Chinese-majority PAP as a threat to Malay rights in the new Federation.

Both leaders oversaw periods of industrialisation and rapid development, leading their countries to growth through a turbulent economic climate. Both were straight-talking, hard-nosed politicians unafraid to speak their mind, especially against the Western ideal of a democratic leader. Both gained infamy for suing and/or detaining their critics for—if we’re being honest—purely political reasons.

However, the differences are stark. Mahathir began his political life as a party pariah; LKY was his party’s co-founder and de facto leader from the get-go. Mahathir championed Malay rights; LKY saw multiculturalism as the only path to success. LKY had no kings to contend with; Mahathir had nine—a conflict that continues to present day.

And, perhaps most importantly, LKY cemented the political succession of Singapore in the hands of the PAP; Mahathir hand-picked his UMNO successors, who ultimately proved to be political failures.

But today, LKY is dead, and Mahathir is Prime Minister once more. Whoosh.

Petrobras scandal takes down the centre-left government party? Bolsonaro’s your man. Manila is awash with drugs? Kill ‘em all, says Duterte.

There’s something refreshing about a politician who (appears) to be telling the truth—but that creates enemies.

Fortunately, part of a strongman’s appeal is that he gives you someone to root for who’s in opposition to someone else that you can safely detest. For Bolsonaro, it’s the left; for Duterte, it’s the criminals; for MM Lee, it was the liberal Western media; for Mahathir, it was… us?

But that’s where the similarities end.

To liken Dr M and LKY to the modern brand of nationalist-populist-politician—brash, tasteless, and uncultured (lookin’ at you, Donald)—is a gross mischaracterisation. It’s also one on which modern autocrats have capitalised.

LKY was not a proponent of easy lies, but of hard truths; the same can be said of Dr M (I make no claims regarding the accuracy of the ‘truths’ nor the inaccuracy of the ‘lies’).

In 1970, while still a party outcast, Dr M wrote The Malay Dilemma, in which he criticised Malaysian Chinese hegemony—but also dissected the perceived failings of his own race. In 2018, he commented that Malaysians “don’t want to work because the government gives them money.”

Yes, he actually said that. Of the people who voted him into power.

Well, not really.

Part of the problem with such an approach in a modern and media-saturated democracy is that leaders can’t just arrest whomever they choose and wait for it to blow over, while letting the electorate’s short attention span do the work for them. They can ‘sue until pants drop’, but that doesn’t sting quite the same, especially with the proliferation of social media and alternative narratives that paint such leaders in a bad light.

Perhaps the other reason such a leadership style will never re-surface in Singapore is that the OG actually succeeded. Lee Kuan Yew, for all the allegations and criticisms, appeared to keep his robes white, ushering in a clean system that needed neither further imprisonments nor public show trials.

On the other hand, Mahathir engaged in the most ancient and most obvious form of corruption: institutional racism. To his mind, he was merely correcting a form of corruption practised by the British. In reality, the notion of bumiputera—that Malays have First Rights when it comes to education, business, and welfare—has been bloated to become a shorthand to Malay-dominated superiority, corruption, racism, apartheid, and everything in between.

If not a corrupt man, he was regarded as an enabler of corruption by detractors in subsequent decades.

But the past is washed away; he’s back and the people are joyous. Are they, though?

“He changed a few rules, which have impacted us,” says a relative of mine, a Malaysian citizen. “Nothing really major yet. I’m reserving judgement.”

Another Malaysian lists his positive attributes in her eyes: above average intelligence, physical and mental stamina, charisma, lots of hard work and effort.

“Unfortunately,” she sighs, “The Malay/Muslim agenda in all his development plans… brought the country down. Even if he has realised that now, time is not on his side. [It’s] so difficult to reverse all his mistakes. I regret [that] he didn’t do better for this country when he could have.”

Singaporeans’ perception of Mahathir are twofold. While he’s certainly more well-respected, since the unearthing of former Prime Minister Najib Razak’s massive corruption scandal, Dr M’s historic antagonism towards Singapore has come to the surface once more. Since taking power, Dr M’s government has bickered with Singapore over water, airspace, and maritime boundaries. Despite this, Mahathir maintains that he is not anti-Singapore—just pro-Malaysia.

In any case, this term represents a final chance for the last member of Asia’s ‘Old Guard’. Where before, he picked a successor whom he ultimately grew to criticise, he has now been given something few leaders are ever afforded: a do-over. With his old ally, Anwar Ibrahim, looking set to succeed him, this may be Dr M’s chance to right his many wrongs.

Iron leadership may be dead, but Malaysia’s last ironman is taking his last shot at fixing the system, the only way he knows how: putting on those knuckle dusters and wading back into the ring.